Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change

The time has come to rethink religion's public role in order to ensure equality and fairness for believers and non-believers alike, says a major new report launched by the National Secular Society.

The report says that Britain's "drift away from Christianity" coupled with the rise in minority religions and increasing non-religiosity demands a "long term, sustainable settlement on the relationship between religion and the state".

Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change has been sent to all MPs as part of a major drive by the Society to encourage policymakers and citizens of all faiths and none to find common cause in promoting principles of secularism.

It calls for Britain to evolve into a secular democracy with a clear separation between religion and state and criticises the prevailing multi-faithist approach as being "at odds with the increasing religious indifference" in Britain.

Terry Sanderson, National Secular Society president, said: "Vast swathes of the population are simply not interested in religion, it doesn't play a part in their lives, but the state refuses to recognise this.

"Britain is now one of the most religiously diverse and, at the same time, non-religious nations in the world. Rather than burying its head in the sand, the state needs to respond to these fundamental cultural changes. Our report sets out constructive and specific proposals to fundamentally reform the role of religion in public life to ensure that every citizen can be treated fairly and valued equally, irrespective of their religious outlook."

Read the report:

Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change

Add your endorsement to the manifesto for change

Add your endorsementComplete list of recommendations

Our changing society – Multiculturalism, secularism and group identity

1. The Government should continue to move away from multiculturalism and instead emphasise individual rights and social cohesion. A multi-faith approach should be avoided.

2. The UK is a secularised society which upholds freedom of and from religion. We urge politicians to consider this, and refrain from using "Christian country" rhetoric.

The role of religion in schools

Faith schools

3. There should be a moratorium on the opening of any new publicly funded faith schools.

4. Government policy should ultimately move towards a truly inclusive secular education system in which religious organisations play no formal role in the state education system.

5. Religion should be approached in schools like politics: with neutrality, in a way that informs impartially and does not teach views.

6. Ultimately, no publicly funded school should be statutorily permitted, as they currently are, to promote a particular religious position or seek to inculcate pupils into a particular faith.

7. In the meantime, pupils should have a statutory entitlement to education in a non-religiously affiliated school.

8. No publicly funded school should be permitted to prioritise pupils in admissions on the basis of baptism, religious affiliation or the religious activities of a child's parent(s).

9. Schools should not be able to discriminate against staff on the basis of religion or belief, sexual orientation or any other protected characteristics.

Religious education

10. Faith schools should lose their ability to teach about religion from their own exclusive viewpoint and the law should be amended to reflect this.

11. The Government should undertake a review of Religious Education with a view to reforming the way religion and belief is taught in all schools.

12. The teaching of religion should not be prioritised over the teaching of non-religious worldviews, and secular philosophical approaches.

13. The Government should consider making religion and belief education a constituent part of another area of the curriculum or consider a new national subject for all pupils that ensures all pupils study of a broad range of religious and non-religious worldviews, possibly including basic philosophy.

14. The way in which the RE curriculum is constructed by Standing Advisory Councils on Religious Education (SACREs) is unique, and seriously outdated. The construction and content of any subject covering religion or belief should be determined by the same process as other subjects after consultation with teachers, subject communities, academics, employers, higher education institutions and other interested parties (who should have no undue influence or veto).

Sex and relationships education

15. All children and young people, including pupils at faith schools, should have a statutory entitlement to impartial and age-appropriate sex and relationships education, from which they cannot be withdrawn.

Collective worship

16. The legal requirement on schools to provide Collective Worship should be abolished.

17. The Equality Act exception related to school worship should be repealed. Schools should be under a duty to ensure that all aspects of the school day are inclusive.

18. Both the law and guidance should be clear that under no circumstances should pupils be compelled to worship and children's right to religious freedom should be fully respected by all schools.

19. Where schools do hold acts of worship pupils should themselves be free to choose not to take part.

20. If there are concerns that the abolition of the duty to provide collective worship would signal the end of assemblies, the Government may wish to consider replacing the requirement to provide worship with a requirement to hold inclusive assemblies that further pupils' 'spiritual, moral, social and cultural education'.

Independent schooling

21. All schools should be registered with the Department for Education and as a condition of registration must meet standards set out in regulations.

22. Government must ensure that councils are identifying suspected illegal, unregistered religious schools so that Ofsted can inspect them. The state must have an accurate register of where every child is being educated.

Freedom of expression - Freedom of expression, blasphemy and the media

23. Any judicial or administrative attempt to further restrict free expression on the grounds of 'combatting extremism' should be resisted. Threatening behaviour and incitement to violence is already prohibited by law. Further measures would be an illiberal restriction of others' right to freedom of expression. They are also likely to be counterproductive by insulating extremist views from the most effective deterrents: counterargument and criticism.

24. Proscriptions of "blasphemy" must not be introduced by stealth, legislation, fear or on the spurious grounds of 'offence'. There can be no right to be protected from offence in an open and free secular society.

25. The fundamental value of free speech should be instilled throughout the education system and in all schools.

26. Universities and other further education bodies should be reminded of their statutory obligations to protect freedom of expression under the Education (No 2) Act 1986.

Religion and the law

Civil rights, 'conscience clauses' and religious freedom

27. We are opposed in principle to the creation of a 'conscience clause' which would permit discrimination against (primarily) LGBT people. This is of particular concern in Northern Ireland.

28. Religious freedom must not be taken to mean or include a right to discriminate. Businesses providing goods and services, regardless of owners' religious views, must obey the law.

29. Equality legislation must not be rolled back in order to appease a minority of religious believers whose views are out-of-touch with the majority of the general public and their co-religionists.

30. The UK Government should impose changes on the rest of the UK in order to comply with Human Rights obligations. Every endeavour should be made by to extend same sex marriage and abortion access to Northern Ireland.

Conscience 'opt-outs' in healthcare

31. Efforts to unreasonably extend the legal concept of 'reasonable accommodation' and conscience to give greater protection in healthcare to those expressing a (normally religious) objection should be resisted.

32. Conscience opt-outs should not be granted where their operation impinges adversely on the rights of others.

33. Pharmacists' codes should not permit conscience opts out for pharmacists that result in denial of service, as this may cause harm. NHS contracts should reflect this.

34. Consideration should be given to legislative changes to enforce the changes to pharmacists codes recommended above.

The use of tribunals by religious minorities

35. The legal system must not be undermined. Action must be taken to ensure that none of the councils currently in operation misrepresent themselves as sources of legal authority.

36. Work should be undertaken by local authorities to identify sharia councils, and official figures should be made available to measure the number of sharia councils in the UK to help understand the extent of their influence.

37. There needs to be a continuing review by the Government of the extent to which religious 'law', including religious marriage without civil marriage, is undermining human rights and/or becoming de facto law. The Government must be proactive in proposing solutions to ensure all citizens are able to access their legal rights.

38. All schools should promote understanding of citizenship and legal rights under UK law so that people – particularly Muslim women and girls – are aware of and able to access their legal rights and do not regard religious 'courts' as sources of genuine legal authority.

Religious exemptions from animal welfare laws

39. Laws intended to minimise animal suffering should not be the subject of religious exemptions. Non-stun slaughter should be prohibited and existing welfare at slaughter legislation should apply without exception.

40. For as long as non-stun slaughter is permitted, all meat and meat products derived from animals killed under the religious exemption should be obliged to show the method of slaughter.

41. In public institutions it should be unlawful not to provide a stunned alternative to non-stun meat produce.

Religion and public services

Social action by religious organisations

42. The Equality Act should be amended to suspend the exemptions for religious groups when they are working under public contract on behalf of the state.

43. Legislation should be introduced so that contractors delivering general public services on behalf of a public authority are defined as public authorities explicitly for those activities, making them subject to the Human Rights Act legislation.

44. It should be mandatory for all contracts with religious providers of publicly-funded services to have unambiguous equality, non-discrimination and non-proselytising clauses in them.

45. Public records of contracts with religious groups should be maintained and appropriate measures for monitoring their compliance with equality and human rights legislation should be put in place.

46. There should be an enforcement mechanism for the above, which would for example receive and adjudicate on complaints without complainants having to take legal action.

Hospital chaplaincy

47. Religious care should not be funded through NHS budgets.

48. No NHS post should be conditional on the patronage of religious authorities, nor subject directly or indirectly to discriminatory provisions, for example on sexual orientation or marital status.

49. Alternative funding, such as via a charitable trust, could be explored if religions wish to retain their representation in hospitals.

50. Hospitals wishing to employ staff to provide pastoral, emotional and spiritual care for patients, families and staff should do so within a secular context.

Institutions and public ceremonies

Disestablishment

51. The Church of England should be disestablished

52. The Bishops' Bench should be removed from the House of Lords. Any future Second Chamber should have no representation for religion whether ex-officio or appointed, whether of Christian denominations or any other faith. This does not amount to a ban on clerics; they would eligible for selection on the same basis as others.

Remembrance

53. The Remembrance Day commemoration ceremony at the Cenotaph should become secular in character. Ceremonies should be led by national or civic leaders and there should be a period of silence for participants to remember the fallen in their own way, be that religious or not.

Monarchy and religion

54. The ceremony to mark the accession of a new head of state should take place in the seat of representative secular democracy, such as in Westminster Hall and should not be religious.

55. The monarch should no longer be required to be in communion with the Church of England nor ex officio be Supreme Governor of the Church of England, and the title "Defender of the Faith" should not be retained.

Parliamentary prayers

56. We believe Parliament should reflect the country as it is today and remove acts of worship from the formal business of the House.

Local democracy and religious observance

57. Acts of religious worship should play no part in the formal business of parliamentary or local authority meetings.

Public broadcasting, the BBC and religion

58. The BBC should rename Thought for the Day 'Religious thought for the day' and move it away from Radio 4's flagship news programme and into a more suitable timeslot reflecting its niche status. Alternatively it could reform it and open it up to non-religious contributors.

59. The extent and nature of religious programming should reflect the religion and belief demographics of the UK.

Add your endorsement to the manifesto for change

Add your endorsementThe 2017 General Election

‘Islamophobia’ distracts from tackling anti-Muslim bigotry

We need to tackle anti-Muslim hate, but the politicised and problematic term of Islamophobia should be ditched, argues Nova Daban.

As we reach the end of 'Islamophobia Awareness Month' (IAM), the term 'Islamophobia' itself continues to generate endless debates, leaving it with no agreed definition.

Despite the term being used to describe prejudice and hateful attitudes towards Muslims, it has also been used to shield Islam from criticism, even hampering efforts to challenge extremism. The concept of Islamophobia risks creating a blasphemy code inimical to free speech and a secular liberal democracy.

There are several other terms that could be used to describe the verbal and physical abuse Muslims receive. Anti-Muslim bigotry or hatred, for example. Or even Muslimophobia. So why the insistence on a term that continues to be controversial and continuously fails to gain widespread support from civil society or the government?

IAM aims to "highlight the threat of Islamophobic hate crimes" and "showcase the positive contributions of British Muslims to society". Off the back of this there have been a couple of recent exchanges in Parliament about the failure to establish a working definition of the term. In a House of Lords debate, the government acknowledged that 45% of religious hate crimes were targeted at Muslims but warned that the term was being weaponised by groups to undermine free speech.

There is no dispute about the need to address anti-Muslim bigotry, but attempting to do so at the expense of freedom of expression will be counterproductive.

Another reason to be cautious around the IAM campaign is that they claim to have been co-founded by MEND. The organisation's former director of engagement Azad Ali has previously stated that the Islamist-inspired 2017 Westminster attack, in which Khalid Masood killed five people, was "not terrorism". He also described al-Qaeda terrorist Anwar al-Awlaki in 2008 as "one of my favourite speakers" and spoke affectionately of him, stating "I really love him for the sake of Allah."

The term 'Islamophobia' arms Islamists with a weapon to attack anyone that criticises anything and everything related to Islam, from religious texts to misogyny and even terrorism carried out in its name. A very recent example of this is a Canadian school cancelling a Nadia Murad event because "it would foster Islamophobia". Nadia Murad, a Yezidi victim of ISIS, was enslaved and raped by the Islamist terrorists during their onslaught in Iraq and Syria. She describes the horror she faced at the hands of the Islamic State's brutality in a new book called The Last Girl.

For many Muslims, there is nothing more offensive than brutal terrorists attempting to hijack their religion and destroy its reputation. So why is it 'Islamophobic' to discuss terrorism, enslavement, and rape?

How far do we go in branding criticism of ancient and regressive religious and cultural practices as Islamophobic? Muslim-majority countries such as Syria, Algeria and Kazakhstan have banned full-face veils (niqabs and burqas) in certain contexts on the basis that they compromise security and symbolise discrimination against women. Suggesting anything along these lines in countries like the UK automatically leads to accusations of Islamophobia. Do you then stay consistent and call Muslims that support such moves "Islamophobic", or do you stop and think about why debates are also taking place in Muslim societies?

The hostility faced by many Muslims just trying to live their lives in peace should be condemned in the strongest possible terms. Anti-Muslim bigotry is real, and those championing human rights and a truly secular society should do more to fight it. We need to combat far-right terrorism that targets Muslims, such as the mosque attack in New Zealand. We must confront China's oppression of Muslims in Xinjiang. Muslims should not have to fear for their safety. But this is no reason to promote the double-edged sword of Islamophobia, which is politically loaded and polarising.

The UK government should resist pressure to adopt a working definition of 'Islamophobia' and come up instead with a strategy to tackle anti-Muslim bigotry. This will ensure we can tackle discrimination against Muslims, whilst keeping blasphemy codes at bay and keep everyone safe from extremism.

Don’t sacrifice the principle of universal human rights to religious leaders

A recent report on state-sanctioned killings of 'blasphemers' and 'apostates' suggests re-interpreting Islam as a solution rather than promoting universal human rights. Megan Manson argues this is the wrong approach.

Last month Monash University released a report highlighting the appalling atrocities committed due to 'blasphemy' laws.

'Killing in the name of God: State-sanctioned violations of religious freedom' exams the twelve countries where 'apostasy' and/or 'blasphemy' are punishable by death*. Eleven of those countries have Islam as the state religion. The exception, Nigeria, has no state religion but the twelve Nigerian states in which blasphemy is punishable by death operate a sharia law system in parallel to secular courts. The death penalty is justified through statements in Islamic texts calling for those who change religion to be killed.

While actual executions for these 'crimes' are rare, the report explains how the death penalty for religious offences contributes to extrajudicial killings and killings by civilians and extremist groups.

For example, Pakistan pursues high volumes of prosecutions for blasphemy, but it has never conducted a judicial execution on this basis. The report suggested the combination of taking such a strict stance against blasphemy and failing to carry out death sentences encourages mobs and vigilantes to do the dirty work on behalf of the state. One victim of this approach was Tahir Naseem, an Ahmadi Muslim who was shot dead while standing trial for blasphemy last year.

The report also highlights how trumped-up charges of political and security-related offences are used to convict and execute religious minorities and dissidents. By adopting Islam as the state religion, the government can frame acts against religion as acts against the state.

'Killing in the name of God' is an important report and must be commended for raising the plight of those targeted by blasphemy and apostasy laws around the world. It does not shy away from explicitly demonstrating the link between Islamic theology, Islamic theocracy, and state-sanctioned killings.

What's less encouraging are the report's suggestions for ending these killings.

It says: "rather than framing advocacy in the language of human rights, a better alternative would be to work with pre-existing normative structure, such as promoting a contemporary understanding of Islam that rejects the retention of the death penalty".

The report advocates the involvement of faith leaders in this approach, stating that their role in campaigning for human rights "cannot be understated" and that as "respected figureheads and custodians of religion, faith leaders may be better positioned to inspire respect for human rights than those perceived as foreign."

The report concludes: "The Qur'an embraces religious freedom, and as we have shown, the abolition of the death penalty for religious offences is entirely compatible with its teachings".

No doubt the authors believe shoehorning human rights into an Islamic framework, rather than promoting human rights as a universal for all regardless of religion or belief, would be more palatable for leaders in theocracies such as Iran, which has challenged the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as "a Western concept of Judeo-Christian origin."

But by playing into these arguments rather than challenging them, 'Killing in the name of God' ignores the likely undesirable consequences of this approach.

For example, there are plenty of individuals and organisations in these countries who embrace the concept of universal human rights. These people are no more 'foreigners' in their countries than the Islamic fundamentalists, but suggesting their values are 'foreign' adds to their alienation.

Take Leo Igwe, founder of the Humanist Association of Nigeria. Igwe tirelessly campaigns on a wide variety of issues, including combatting 'witchcraft' persecution, defending LGBT+ rights, and speaking out for religious minorities. One of Igwe's most recent projects is to introduce lessons on critical thinking into Nigeria's schools.

In between all this, Igwe is fighting to get fellow campaigner Mubarak Bala (pictured) released from his imprisonment in connection with 'blasphemous' Facebook posts. This is not the first time Bala lost his freedom for expressing views that differ from Islam. In 2014 he was confined to a psychiatric hospital for not believing in God.

It's hard to see how the Islamocentric approach advocated by 'Killing in the name of God' can help Nigerians like Igwe and Bala. It would surely reinforce the divide between Nigerian Muslims and atheists – and the power the former has over the latter.

There are many more individuals in these countries who value the concept of human rights for all. The reason why we may not always hear their voices is obvious to anyone who's read the report – anyone who says anything that could be deemed in any way against Islam risks their very life. Surely the solution is to empower the voices of these grassroots activists, rather than trying to appeal to religious leaders who oppress them with watered-down, sharia-compliant versions of 'rights'?

Of course, human rights organisations have a role to play in ensuring those promoting more liberal interpretations of Islam which reject the death penalty, and even better reject the criminalisation of 'blasphemy' and apostasy' altogether, have the freedom to express this. But this does not require us to abandon universal human rights and secular democracy, or those striving to promote both in their own countries.

'Killing in the name of God' is an excellent report, and recommended reading for all those concerned with ending the death penalty for blasphemy and apostasy – and indeed the criminalisation of these concepts. But we should be extremely wary of any solution that elevates religion and religious leaders over universal human rights. Instead of dancing to the tune of theocrats, let's listen to those oppressed by them and let them be heard.

*Those countries are: Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Maldives, Mauritania, Nigeria, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

Picture via Humanists International

‘Inclusive language’ in the army is meaningless without inclusive culture

The Armed Forces must dismantle their institutional Christian privilege if they are truly committed to inclusivity, says Megan Manson.

This article is available in audio format, as part of our Opinion Out Loud series.

The Ministry of Defence has recently released an 'Inclusive Language Guide' (pictured). The guide promotes "using words that refer to everyone and avoiding words that exclude or offend".

On the face of it, the section on "Religion and Belief" looks promising. It offers sensible advice, such as not assuming a person's religion from their name or appearance, or their dietary preferences from their religion.

It's also focused on nonreligious beliefs. This is refreshing; nonreligious people are all too often neglected in conversations about religion or belief inclusion. The guide suggests, for example, using the term 'first name' instead of 'Christian name', and dropping the archaic term "morning prayers" for morning meetings.

This will no doubt be well-received by many nonreligious people in Defence – a demographic which is growing rapidly. The percentage of members of the Armed Forces who say they have no religion has shot up from less than 10% in 2007 to 34% in 2021.

But will a guide on speech truly make the army more inclusive of people of all faiths and none?

The Inclusive Language Guidance suggests the army is aware that prayers can be divisive and alienating for those who don't share in that tradition. It is therefore strange that while the guidance advises avoiding the word 'prayer' to refer to morning meetings, little has been done to address the actual prayer and religious services that are an inescapable part of life in Defence.

The Queen's Regulations for the Army (QRs), which set out the policy and practice of the army, were recently updated to specify that soldiers may not be compelled to attend acts of religious observance against their wishes. But this is negated by another clause in the regulations stating commanders may order a parade that includes a religious service which soldiers are expected to attend. In other words, soldiers who don't wish to pray must stand by silently while their comrades take part in the invariably Christian ceremony.

Such parades may include acts of remembrance, important occasions for all serving in Defence. While the Army General Administrative Instructions state that acts of remembrance should be "inclusive" and "separate religious elements from those that pay tribute to the fallen", in practice Christian prayers are still incorporated seamlessly into the proceedings with little separation.

The only way to avoid the religious parts is to not attend at all – and that is neither a realistic nor desirable option for personnel. Regardless of religion or belief, all soldiers want to take a full and active part in their unit's act of remembrance – but how can they do so when it is an act of worship?

Christian acts of worship pepper army life far beyond remembrance services. Units have their own 'corps collects', or prayers which mentions the unit. Army chaplains may be called upon to bless flags and ships. And 'passing out' parades for new soldiers may incorporate a Christian blessing, such as this one held by the Army Foundation College in February.

The only way to make military events truly inclusive of non-Christians is to remove Christian rituals from official proceedings, and so put Christianity on the same footing as all other religions and beliefs.

Another area of army life where Christian privilege is particularly acute is chaplaincy. Only ministers of a select group of eight 'sending churches', all Christian, may be chaplains (or 'padres') of regular army units.

When it comes to other religions, the Armed Forces have appointed religious leaders from the Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim and Sikh faiths to act as "advisers on matters specific to those faith groups", according to its guidance on religion or belief. It says action "is being taken to appoint civilian Chaplains from the faiths other than Christian most represented within the Armed Forces."

But there is no equivalent 'chaplain' specifically for the nonreligious. The guide says: "Should non-religious personnel in the Armed Forces wish to discuss their beliefs or problems with someone other than chaplains, there are a wide range of non-religious organisations which provide support and advice, including social workers, doctors and other professionals."

In other words, personnel who require nonreligious pastoral support are told that the army will not help them and they must go elsewhere.

According to the Army's recruitment page, chaplains "join the Army as a Captain earning £48,999." It hardly seems inclusive to offer such a prestigious and well-paid role only to Christians for the benefit of Christians, and nothing at all for the nonreligious.

And in addition to chaplains, the army permits an evangelical Christian group, The Soldiers' and Airmen's Scripture Readers Association (SASRA), unfettered access to "to share the gospel within the gated communities where the Army and the RAF are based". SASRA states its charitable objects as "to spread the saving knowledge of Christ among the personnel of HM forces in any part of the world." In other words, SASRA has a specific proselytising agenda.

Christian privilege in the army not only adversely affects nonreligious personnel and those who belong to minority faiths. It also impacts soldiers who are LGBT.

The 'sending churches' include denominations notorious for their anti-LGBT views, including the Free Church of Scotland, Elim Pentecostal Church and the Salvation Army. As military chaplains are required to "set forth God's word at all times" according to the Royal Army Chaplains' Department, what does this mean for gay soldiers who come to the chaplain with relationship problems, for example? Will they receive impartial and non-judgmental counselling if the chaplain sees their lifestyles as sinful?

Then there is the issue of same-sex marriages on military premises. Those who wish to marry on barracks have no option but the military chapel – which is largely under the control of the sending churches, most of which object to same-sex marriage.

As a result, while there are 190 military chapels in England and Wales registered for marriages, there has only been one gay wedding in a military chapel since same-sex marriage was legalised in 2014. Because there are no secular provisions for weddings on military sites, gay personnel have no meaningful options but to marry on a civilian site.

There are some encouraging signs of policy change that may indicate the army is waking up to the problems caused by its Christian bias.

Previously, QRs in effect make it impossible for atheists to become commanding officers, because the regulations imposed a duty on commanding officers to "encourage religious observance by those under their command" and to "set a good example in this respect". The QRs also required soldiers to get permission to change religion and said the "reverent observance" of religion in the armed forces is of the "highest importance".

Following long campaigning efforts from armed forces members, the QRs have now thankfully been recently revised to remove these unfair and illiberal requirements from the regulations.

The Armed Forces are clearly concerned about inclusivity, and over the years they have made many changes to make themselves more welcoming to all.

But it's also clear Christianity still holds a disproportionate sway over what is an increasingly irreligious and religiously-diverse army. If our Armed Forces are sincere in their desire to be welcoming to all, inclusive language is not enough – bold action is needed to ensure personnel of all religions and none are treated equally and fairly.

With special thanks to Lt Col (Retd) Laurence Quinn for his contributions.

Lt Col Quinn has produced two reports on the issue of inclusion of the nonreligious in the army; you can read them here and here.

A vision for inclusive assemblies for all

Paul Stanley's work shows how much more inclusive and engaging school assemblies could be without the anachronistic legal requirement for religious worship, argues Sue Garratt.

My husband Paul Stanley was a schoolteacher for 12 years and a headteacher for 15. He died in September 2019 aged only 54. Despite being head of a large Church of England school, he was a staunch atheist and a long-term member of the NSS. Naturally, this led to much wrestling of conscience: it was not always easy juggling his professional duty with his firmly held beliefs that a school wasn't a religious community and no place for leading worship.

Paul ran countless school assemblies over many years. He saw value in a whole school community gathering together regularly to reflect on the many significant issues that he felt were important for children to understand. However, he found it unacceptable that schools, well into the 21st century, still have a legal obligation to implement a daily act of collective worship.

Although this may be widely ignored, he thought it anachronistic that it is still written in law, as well as being enforced and inspected in faith schools. Despite having a good relationship with the Church, Paul resented the implication and the expectation that he should be some kind of religious leader when he stood in front of the children for a whole school assembly.

It was, of course, very important to him to be a positive role model for the children in his care. He wanted to make them think about the world, and he was more than capable of doing this, and of furthering their learning, knowledge and understanding, their social and moral development, and their wonder and appreciation of the world around them without leading worship and without recourse to any god. He was always very clear that he didn't enter the teaching profession to be an advocate for any religion.

Paul understood that school aged children becoming ever more diverse and nonreligious meant that they were more likely to access the moral messages if they weren't taught using religion. He was also frustrated by the fact that most published assembly materials focused on religious references and prayers, so he spent many years creating his own.

In the autumn of 2018, when Paul's illness was first diagnosed, he decided to publish his collection of assemblies, hoping to provide a useful resource to reduce the burden on over-worked headteachers. A book deal followed just before he became too ill to work, and 'Assemblies for All' was published posthumously in March 2021.

The best of Paul's assemblies are gathered in this book which is aimed mainly at Key Stage 2 pupils. The many themes covered include: creativity, humility, peace, thankfulness, truth and promises, animal rights, service to others, justice and fairness, overcoming adversity, courage, trust, perseverance, and the importance of friendship. None of these of course has anything to do with worship or requires religion.

Paul saw a significant gap in the market for an engaging assembly resource book written by a serving headteacher and with all children's interests and needs at its heart. Paul felt that it was more important than ever that children examine such themes and values at a time when the school curriculum has, sadly, become 'squeezed', narrow and results driven.

When he died, tributes from the school community flooded in. Parents said he was empathetic, understanding, and honest. Pupils raved about his 'cool' assemblies, and described him as 'respectful, decent, supportive, kind, and caring to children'.

Paul knew what made children tick. His wealth of experience in schools, as well as his humanity and compassion, are apparent from his assemblies. Positive messages are emphasised, and global human issues are explored, in thought-provoking ways – and without wedging in any deity.

Paul made a huge difference to many people's lives over the years. I hope he will, through his book, continue to have an impact on even more children in the future.

Assemblies for All: Diverse and exciting assembly ideas for all Key Stage 2 children, £22.49

Image: Assemblies for All cover (cropped)

Islamist extremism won’t be addressed by ignoring it

The national conversation following the brutal killing of David Amess suggests an unwillingness to tackle the Islamic extremism behind it, argues Stephen Evans.

The brutal killing of David Amess, stabbed to death at his Essex constituency surgery last week, was a vile, cowardly attack on decency and democracy.

The utter senselessness and callousness of this killing makes it hard to comprehend.

MPs and commentators have understandably expressed shock and grief, taken time to remember a man who dedicated his life to public service, and reflected on his legacy.

But the national conversation around Sir David's killing has also taken a bizarre turn on the issue of what caused it.

In no time at all commentators were blaming the "toxic political discourse" and "social media internet trolls" who hide behind anonymity while spreading hate.

This certainly is an issue, but it doesn't appear to be the issue, not as far as this murder is concerned.

The crime is being investigated as a terrorist incident. The suspect, Ali Harbi Ali, a Briton of Somali heritage, appears to have links to Islamic extremism, and was previously referred to the counterterrorist Prevent scheme. The Crown Prosecution Service will submit to the court that the murder had both religious and ideological motivations.

Nevertheless, the conversation has remained fixed on social media abuse. It's almost as if the facts were inconvenient to the narrative, so have been ignored.

The only mention of Islam in the many moving tributes to David Amess in Parliament on Monday was in the context of 'Islamophobia'. Politicians appear keener to debate the definition of 'Islamophobia' than tackle Islamist extremism. Many seem more interested in undermining Prevent and making counter-radicalisation efforts as toothless as possible than advancing ways to keep society and those at risk of radicalisation safe.

This perhaps speaks to the troubling political influence of certain Muslim lobby groups who are more interested in peddling victimhood than addressing the issues of extremism within Islam.

We all need to be a bit less squeamish about this. Research last year found the majority of British Muslims are concerned about Islamist extremism and support the principles behind the Prevent programme. This isn't surprising. Muslims who see no contradiction between their religious identity and loyalty to British values so often find themselves at the sharp end of Islamist intolerance.

There's nothing 'Islamophobic' about addressing concerns shared by Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

We must accept that the poison of Islamist extremism is prevalent in Britain and poses a real threat to our liberal values and fragile democracy. There is an enemy within. It's not Muslims; it's those who seek to use violence and threaten basic liberal values such as freedom and democracy. MI5 is aware of more than 43,000 people who pose a potential terrorist threat to the UK. Ninety per cent of the watchlist is thought to be made up of Islamic extremists.

The separatist ideology at the root of Islamist extremism is being preached in British mosques - more than half of which are now thought to be under the control of the puritanical and orthodox Deobandi brand of Islam. A new book by Ed Husain, Among the Mosques, paints an alarming picture of parallel societies developing in parts of Britain, fuelled by mosques preaching an illiberal Islam that not only promotes intolerance but also fosters extremism.

Meanwhile, Islamist extremists who preach hatred, sow division, and promote sectarianism have exploited a charity system that grants organisations charitable status on the basis that they exist for the 'advancement of religion', one of the charitable purposes set out in law.

One example is a charity which is now being investigated after the NSS recently referred it to the regulator. The charity's aims and objectives include "to further the true image of Islam". On its website we found sermons praising the Taliban, encouraging Muslims to fund jihadists, and referring to the "dirty qualities" of Jews.

Then consider that this year, in Batley, an intolerant minority of extremists protesting outside school gates dictated what can and can't be taught in British schools. A teacher was effectively hounded out of his job for using cartoons of a religious figure to teach about free speech and blasphemy. He now lives in fear for his life after facing death threats. The curriculum was changed while the government stood idly by, and so-called liberals quietly acquiesced.

Meanwhile, young minds are being closed in Islamic schools that promote sectarianism and segregation, whilst paying lip service to their duty to promote fundamental British values.

One reason why this is happening is because the few people willing to speak up about it are quickly dismissed as Islamophobic, a slur akin to racism, that can seriously damage reputations.

As far as politicians are concerned, these problems find their way into the 'too difficult' box: a place for all the unpopular subjects that governments and their civil servants aren't prepared to confront. So instead, lawmakers fixate on laws to crack down on speech and stop people being horrible to each other on the internet.

People should definitely stop being horrible to each other on the internet. And public servants must be free to do their jobs without fear and intimidation. But that alone won't address the myriad problems posed by radical Islam.

There was a moment in 2015, during David Cameron's premiership, when the government appeared determined to confront Islamist extremism by defending secular liberal democracy and building a more cohesive society. But many in positions of power now seem to have given up.

Never mind being willing to tackle the problem. The discourse following the killing of David Amess suggests we hardly seem willing to name it.

Why is the Catholic church allowed to hinder secondary school choice?

A case in Leicestershire shows the mess faith groups make of admissions and why secular accountability is necessary, argues Alastair Lichten.

The practice of state funded faith schools discriminating in favour of prospective pupils on the basis of their parents' religion is well known. 'On your knees, avoid the fees' has become common parlance in conversations about religiously selective state schools. But the ways in which faith schools undermine families' choices can be more diverse, complex, and occasionally counterintuitive.

The problem of families being pushed into a faith school, because of a lack of options or faith groups' influence over other education decisions, is less visible. A case in Leicestershire, now the subject of a legal challenge, provides one such example.

Parents at St Thomas More, a Catholic primary school in Leicester, claim the Catholic Diocese of Nottingham which runs the school is fostering discrimination by impeding a meaningful choice of secondary school. The diocese is blocking local non-faith (community-ethos) schools from listing St Thomas More as a feeder. This leaves parents at the school with almost no options but St Paul's Catholic School, a secondary school run by the diocese's trust.

Another community-ethos academy affected by the diocese's meddling is Beauchamp College. When they consulted on listing St Thomas More as a feeder, the diocese wrote to all parents, in a tone described as "intimidating", criticising support for the plan. In 2020, 45 St Thomas More parents called for the move, followed by 60% of consultation respondents. However, the diocese remained adamant that St Thomas More pupils are expected to transfer to St Paul's.

The head of the diocese's academy trust Neil Locker said neither they, nor the bishop, would allow any Catholic school to associate as a feeder with any non-Catholic school, because the relationship between primary and secondary schools "is fundamental and sacrosanct".

Another community ethos secondary school affected is Manor High School. When this school consulted local primary schools on its plans to update its feeder schools, St Thomas More's academy trust decided not to inform parents, in a possible breach of the School Admissions Code.

St Thomas More parents have been fighting for years to be given an equal choice of secondary schools. They describe the decision not to designate the school as a feeder for Manor High School as "a complete surprise and shock".

Frustrated by the diocese's influence over school choice, one parent is taking legal action with the Office of Schools Adjudicator (OSA), a body which helps to clarify the legal position on admissions policies, seeking to challenge the decision of the non-faith secondary schools not to list St Thomas More as a feeder.

The parent leading the legal action said: "I am doing this because many parents were unaware that they were being implicitly tied into a rigid sort of 'contract of Catholic faith education' that, effectively, means parents forgo their choice of non-Catholic secondary schools.

"This was not an informed decision for a substantial number of parents. Being locked into a consumer or employment contract with no exit strategy would never be accepted in any other area of society."

NSS research shows 260 pupils across Leicester and Leicestershire were assigned faith schools against parental preferences this year. Thirty-six per cent of pupils in the county have little choice but a faith-based primary, and the diocese's policy will leave many with little choice but a faith-based secondary school.

A representative of the Doyle Clayton legal firm supporting the case said, if successful, it "will help to ensure that children's secondary school choices are not restricted by the faith of their primary school and by a 'feeder school' system that funnels children into faith schools."

"By operating in this manner, the current system is limiting parents' choices of non-faith 'good' schools in their area, ultimately forcing a Catholic education onto children due to a lack of choice for their parents."

Designating a faith school, as a feeder to a community-ethos school is not straightforward. If this creates an advantage for the faith school pupils, it may risk indirect discrimination. However, in this case all the other local primary schools have been listed by both Manor High School and Beauchamp College. Only St Thomas More is being treated differently, and only at the diocese's behest.

But whatever the arguments for or against specific feeder arrangements, they should not be a matter for the diocese to decide.

The case also raises questions about academisation, and the decreased role of local authorities in admissions. Our research shows that half of former community schools now in multi-academy trusts have some form of religious (normally C of E) governance. If faith-based academy trusts can insist on controlling the admissions of other schools as well as their own, many more families will be locked into faith-based education.

Everywhere you turn, faith schools' institutional and privileged role in admissions creates unnecessary hardship and complexity for parents. It leads to decisions being continually taken in the interests of faith bodies, with little or no genuine transparency or consultation. It's time we had an open, community-led and accountable admissions system, and seriously reevaluate the suitability of faith groups running public schools in an increasingly secular society.

The NSS will be following the case closely. If you have been affected by similar issues, please get in touch.

If you would like to support parents' legal action, a Crowd Justice fundraiser for the legal action is aiming to raise £5,000 by 31 December.

Religion shouldn’t frustrate assisted dying reform

Ahead of parliament's first consideration of assisted dying for six years, Stephen Evans calls on secularists to help ensure that religious objections don't stand in the way of necessary reform.

Later this month peers will debate a new Assisted Dying Bill. The bill, tabled by Molly Meacher, would legalise assisted dying as a choice for terminally ill, mentally competent adults in their final months of life.

By Baroness Meacher's own admission, the bill is "very conservative" and "modest in its scope". Two independent doctors and a High Court judge would have to assess each request, which if granted would enable a terminally ill person with six months or less left to live, to end their life in a manner, time, and place of their choosing.

For some people, the proposed law is too restrictive. Groups such as My Death My Decision argue that choice should be limited not only to those with terminal illnesses but also available to those facing intolerable suffering, as is the case in Canada. But this is not what the bill before parliament proposes.

Despite the bill's narrow scope and stringent safeguards, religious lobby groups are mobilising to oppose it.

This is because a key driver of opposition to greater patient choice at the end of life is the religious idea that God gives and takes life away. The prospect of this being overridden has led the Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales to call the proposed legislation an "unprecedented attack on the sanctity of life". They would prefer all matters of life and death to be left in God's hands.

That may be their view, but it isn't a rational, compassionate, or legitimate basis for policy making. It's not for the state to impose religious dogma on citizens.

Anti-choice activists know this. Their opposition is therefore often framed in secular political or philosophical language. This is of course legitimate. Indeed, as Barack Obama once pointed out, "democracy demands that the religiously motivated must translate their concerns into universal, rather than religion-specific values."

But one downside of this is that it can distort the debate. Dire warnings about the coercion of disabled, elderly, sick or the depressed can mask true motivations for opposing a change in the law. In dressing up religious objections as secular concerns, rather than seeking ways to mitigate potential risks of legalising assisted dying, opponents can exaggerate the risks, weaponising them to spread fear.

For example, evangelical Christian Danny Kruger MP, chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Dying Well, has written to all parliamentarians warning of "widespread euthanasia of the elderly and disabled" if this bill is enacted. The group's website makes no mention of religion, but it's no coincidence that almost all its officers are committed Christians.

Another new anti-assisted dying campaign, 'Better Way', also warns that safeguards will be "completely ineffective". You have to look very hard on their website to find out the campaign is a front for CARE, a Christian charity with theological objections to reform.

Suffering people who would benefit from a change in the law deserve better. That's why it's important to have an open and honest public debate. The British Medical Association's decision to move to a neutral stance on physician-assisted dying is helpful in this regard – as it will enable doctors to fully participate in the debate. And an honest and sincere expression of religious motivations would provide context and enable better assessment and scrutiny of arguments against assisted dying.

But it's worth noting that many religious people support a change in law. A Populus survey commissioned in 2019 found that 80% of religious people supported the legalisation of assisted dying for terminally ill adults with mental capacity. Religious lobby groups and leaders (including the Anglican bishops with a law-making role in the House of Lords) are, as is often the case, out of step on this one.

But for many religious people, such questions are essentially religious ones. For some, their compassion will lead them towards wanting to relieve suffering where possible. But for the more dogmatic, a belief in the sanctity of life makes it hard to accept that individuals should have agency to exert control over the beginning or end of life. They feel this is God's responsibility, not ours. Speaking on the NSS podcast recently, Baroness Meacher recalled a conversation with an archbishop in parliament in which she stressed the importance of autonomy. "I don't know that I believe in autonomy," replied the archbishop.

It's fine for faith to guide the personal decisions of the faithful, but religion shouldn't restrict the freedoms and choices of others. Patient autonomy should be the key guiding principle.

On Friday 22nd October, peers in the House of Lords will debate the bill at its second reading. Religious opponents to assisted dying are making their voices heard. If this bill is to progress to the next crucial stage, it's important that secularists make their voices heard, too. Only then can we overcome the influence, power, and funding of the small, vocal minority who stand against change.

That's why the National Secular Society has teamed up with Dignity in Dying to share their online platform to write to peers in the House of Lords.

There is now overwhelming public support for the law to be reformed to enable assisted dying with robust legal safeguards. As is happening in an increasing number of jurisdictions around the world, legislation can be passed that will fulfil a dual purpose: To protect vulnerable people from pressure to end their lives; whilst supporting people to exercise their autonomy and end their suffering in a humane and dignified manner.

Only secular law can bring justice to victims of mass clerical abuse in France

Keith Porteous Wood says France's deference to the Catholic Church has obstructed justice for hundreds of thousands of abuse victims.

An inquiry commissioned by the Catholic Church into clerical abuse in France has just concluded that victims of both clerics and laity (teachers, for example) totalled around a third of a million since 1950.

In no country in the world has such a high figure been included in an official report. Nearly all victims were minors or vulnerable adults.

The commission, to its credit, held exhaustive hearings in every major town in France. But listening to so many harrowing testimonies took its toll. The president of the commission was not alone in needing psychological assistance.

At the public launch of the inquiry report, abuse survivor François Devaux told Church officials: "You are a disgrace to our humanity. In this hell there have been abominable mass crimes...betrayal of morality, [and] betrayal of children".

The report concluded: "The Catholic Church is, after the circle of family and friends, the environment that has the highest prevalence of sexual violence." Its president accused the Church of "sometimes knowingly putting children in touch with predators."

Prior to this week, the president of the commission was sticking hard to his estimate of 10,000+ victims. In correspondence with him I pointed out the implausibility of this low figure. The final number arrived at by his multidisciplinary team is 330,000.

The estimated number of perpetrators, just 3,000, remains bafflingly small – it equates to 2.6% of priests. In contrast, state-commissioned inquiries by Australia and England & Wales both found 7% of Catholic priests to be perpetrators. The resultant ratio of victims to priests and lay perpetrators cited by the report is a completely implausible - 110:1. A much more realistic figure would be in the range of 10,000 to 30,000 perpetrators - maybe too many for the bishops to handle? Let's hope not.

The key question is, what happens next? Having studied the French Catholic Church closely over the last two years, I'm convinced it's institutionally incapable of putting its own house in order. Even while the report was being written, bishops were distancing themselves from accepting any responsibility. They refused to let their fabulously rich church bear even a centime of the meagre compensation (they recoiled from even using the word), determining that it should be dependent on the amount raised by public subscription. It's thought reparations were conditional on the abandonment of any civil or criminal action. Quite a bargain, for them.

While some give the Church credit for commissioning the report, in my opinion, the Church only did so because it realised that if it did not, the scandals would sooner or later result in a state inquiry. Such an inquiry would have the power to require the production of documents, summon witnesses and examine them under oath.

One of the commission's recommendations was revisions to canon 'law'. Canon 'law' is not an appropriate mechanism for enforcing such rampant criminality; for example, the maximum penalty is removal from the clerical state. The Vatican was urged by the United Nations in 2014 to require such abuse to be reported to the secular authorities, something the current Pope, to his shame, still refuses to do so. He only acts on clerical abuse when absolutely forced to, and usually as little as he can get away with.

It is beyond regrettable that the French state did not institute its own inquiry, as Australia, Germany and England & Wales have done. In contrast, the French National Assembly ignored the matter almost entirely, and the senate's hearings amounted to little more than the Church being asked to sort the matter out itself. That was a monumental failure of secularism.

Devaux accused the Church of cowardice. I charge the state of cowering before the Church. It is almost as if the Revolution never happened; for all practical purposes, the French Church remains above the law and that is the greatest single reason for this, doubtlessly centuries-old, catastrophe.

A state inquiry is still desperately needed. Its terms of reference could be much wider than the commission's. They must include reform of the law and an examination of why around 25 bishops have failed to observe the mandatory reporting law with complete impunity.

The papal adviser on abuse Prof Hans Zollner said yesterday: "If a bishop has not done what the law of his State, and Canon Law, demands of him, then yes [he should resign]." So does that mean we are about to have 25 vacancies? Somehow I doubt it.

France's mandatory reporting law, and the statutes of limitation on abuse and reporting, need urgent reform. As is also needed in the UK, there must be a law requiring those in institutions, including churches, to report reasonable suspicions of abuse to the secular authorities, with safeguards protecting those doing so in good faith. An example of how that might look is here.

No solution is possible without a fit-for-purpose secular law on abuse, and enforcement of such law without fear or favour. France, at present, lacks both.

Image by István Kis from Pixabay

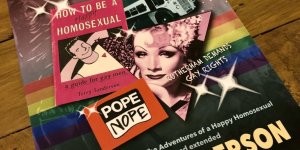

Terry Sanderson’s memoir shows gay and secularist activism go hand in hand

Helen Nicholls reviews The Reluctant Gay Activist, the revised memoir of former NSS president Terry Sanderson.

This article is available in audio format, as part of our Opinion Out Loud series.

"How did I, an ill-educated poverty-stricken lad from a Yorkshire mining town, get swept up in the creation of two of the most amazing and unexpected social revolutions of the past century – gay rights and secularism," asks Terry Sanderson on the first page of his autobiography.

Sanderson was born in 1946 in Maltby, near Rotherham. As a youth, Sanderson knew that he was different to other boys but did not know the reason until he overheard his aunts whispering that the singer Johnnie Ray was "one of them homosexuals". He looked up the word in the dictionary and realised it described him. This was a relief as he reasoned that if there was a word for it there must be others like him.

Until 1967, homosexual acts between men were illegal and even after decriminalisation, there was a strong social stigma. As a young man, Sanderson struggled to meet other gay men until he saw a newspaper advert for 'The Campaign for Homosexual Equality'. He wrote to them and was put in touch with a group in Sheffield. The group was mostly social as its members feared the consequences of public activism. Sanderson later founded a Rotherham group that gradually became more involved in activism.

Sanderson's activism began when he decided to organise gay discos, which led to a long-running battle with the local council which refused to hire out their rooms for gay events. Over the years he became increasingly involved in gay activism as a writer and campaigner. He also wrote books providing advice for gay men such as How to be a Happy Homosexual.

Sanderson's family were never very religious. As a youth he had experimented with different Christian denominations and concluded it was not for him. As he became more involved with gay activism, he saw how much opposition to gay equality came from religious groups. He joined the National Secular Society and became increasingly involved when his partner Keith Porteous Wood became general secretary in 1996. Sanderson joined the NSS council of management and was president from 2006 to 2017.

There was a lot of overlap between gay and secularist activism. Sanderson notes: "I saw the value of secularism in protecting gay rights.

"Religion is the greatest opponent of justice for homosexuals and when laws are made according to religious principles, as they are in much of the Islamic World, then homosexuals become criminalised, persecuted and in constant peril."

Major campaigns during Sanderson's time at the NSS included the abolition of England's blasphemy laws, last used against Gay News in 1977 and finally abolished in 2008, and the protest against the state visit of Pope Benedict who had declared gay and transgender people "a bigger threat to mankind than even the destruction of the rain forests". The NSS also campaigned against religious exemptions to equality law.

During Sanderson's time as NSS president, the organisation shifted its focus from atheism to secularism. Sanderson explains that arguing about religious scripture and belief achieves little and often serves only to entrench the believer's views. However, limiting the political power of religious groups prevents them from imposing their beliefs on others. He has also defended the right of street preachers to read passages from the Bible that condemn homosexuality because his experiences in gay activism have taught him the value of free speech.

In 2017, Terry Sanderson was diagnosed with bladder cancer. The epilogue describes his treatment, which has so far been successful but nevertheless forced him to confront his mortality. His final message is to the next generation. He reflects on the incredible progress that has been made in gay rights in his lifetime. He warns of the growth of religious fundamentalism and notes that homophobia is still widespread. He says that it will be for the next generation of gay people to resist attempts to make them suffer as previous generations did.

The Reluctant Gay Activist is an excellent account of the gay rights and secularist movements as well as an insight into Sanderson's personal history. It shows us how much the world has changed during his lifetime whilst reminding us that we should ensure that future changes are in a positive direction.

Beware the government’s “new normal” of faith-based public services

A new government fund exclusively for faith groups threatens to embed religious privilege into public services, warns Megan Manson.

This article is available in audio format, as part of our Opinion Out Loud series.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government has recently announced a new £1 million pilot fund for organisations that provide community services. But there's a catch – your organisation has to be faith-based in order to qualify.

This is puzzling. There are many charities and other organisations that provide excellent community support. Some have a faith ethos, some do not. So why limit this fund only to groups that are religious?

The very idea seems to fly in the face of equality law. Religion or belief is a protected characteristic in the Equality Act 2010, which means you generally cannot treat people unfavourably due to their religion or their lack of religious beliefs.

What's more, there are genuine concerns about giving certain faith groups unfettered access to public funds for community projects. For some less scrupulous groups, access to large numbers of vulnerable, desperate members of the public is an irresistible opportunity to proselytise. There are also concerns about how inclusive some faith-based charities truly are – just last week, Dundee Foodbank was slammed for advertising for a stock coordinator who can "evidence a live church connection".

Then there are the worries regarding safeguarding. Just weeks ago, the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse highlighted "egregious failings" in the way a wide variety religious organisations have handled child abuse. Surely these issues should be addressed before the government makes overtures to faith groups with the offer of cash?

We're not the only ones concerned. Pragna Patel of Southall Black Sisters, which defends the rights of women in ethnic minority communities, says her own organisation has to "constantly contend" with faith groups that claim to deliver services to women and children subject to domestic abuse but in reality puts them "at further risk of abuse and harm". She says public funds should go to community groups, "especially those working on unpopular issues within their communities such as violence against women and girls".

So why has the government apparently decided that religious groups are more worthy of support than non-religious ones?

The fact is, the government has been building up to this kind of project for some time. It wants faith groups in particular to deliver more of our public services. Last year Conservative MP Danny Kruger released a report recommending the government "invite the country's faith leaders to make a grand offer of help". He dismissed concerns regarding faith-based public services as "faith illiteracy" and "faith phobia".

And in December, the government's 'faith engagement adviser' Colin Bloom launched a biased review into engagement with faith communities seemingly designed to reach a conclusion that would please religious interest groups. The call for evidence attached to the review said: "Because the review is specifically about faith and religion, priority will be given to responses that fit within those parameters." And a press release on the launch said it was calling for views only from "people of all faiths", with no mention of anyone else.

The 'Faith New Deal Pilot Fund' launched this month is the next stage in the government's plan to incorporate religion into the workings of community support. This is quite clear from its prospectus.

The prospectus says the government wishes to "embed 'a new normal' of national government and local government working in partnerships with faith-based groups." It says the 'Faith New Deal' aims to "reset the public sector's mindset towards faith groups."

Danny Kruger has hinted at what may happen if the public sector do not change their mindset, or the wider public do not embrace this "new normal". Individuals who raise concerns about faith groups in public services may stand accused of "faith phobia". In a world where accusations of faith-based "phobia" can result in losing one's job, the threat alone may be enough to silence criticism.

The prospectus also reveals that the outcomes of this pilot "will be captured and fed into a Faith Compact that will be developed". The "Faith Compact" will be "a set of partnership principles for sustainable collaboration between national government, local government and faith communities."

I'm sure it's no coincidence that the 'faith compact' sounds a lot like the 'faith covenant' developed by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on faith and society in order to guide interactions between local authorities, faith groups and the general public.

And it's possibly no coincidence that around the beginning of this year, the faith covenant was quietly changed to remove a clause that stipulated faith groups should refrain from proselytising. This change was made following a meeting of the APPG where one religious leader said this clause was a "stumbling block for a couple of churches".

The NSS previously supported the faith covenant. But since this essential clause was removed, the covenant can no longer be relied upon to protect people from unwanted evangelism.

It's notable that one of the objectives applicants of the 'Faith New Deal' fund must support includes "debt advice". This is where a glaring example of unwanted proselytising regularly occurs. Christians Against Poverty (CAP) is a major provider of debt counselling – and uses that opportunity to preach to vulnerable people in financial trouble. AdviceUK, the national body which represents the interests of advice-providing organisations, has terminated CAP's membership, because it considers the "emotional fee" of the offer or expectation of prayer whilst offering debt advice to fall below the ethical standards expected of service providers.

Since the launch of the 'Faith New Deal', the NSS has written to the ministry on multiple occasions asking what similar support will be available for non-religious groups providing community services, and what safeguards will be put in place to ensure the groups in receipt of the grant do not proselytise and do not exercise any forms of discrimination. So far, no response.

The 'Faith New Deal' fund is religious privilege in action: government funding exclusively for faith groups as part of a scheme to hand over more community services to religion – and to get both local government and the public to accept this as the "new normal".

The prospectus says applicants must show how they will deliver "improved community cohesion", "improved outcomes for marginalised groups" and "build greater trust in local public services". But without addressing the genuine concerns regarding proselytising and discrimination in faith-based public services, the 'Faith New Deal' surely risks undermining all three.

Giving generous funding only to religious groups is divisive and the very antithesis of community cohesion. Having no safeguards to protect people from discrimination will have worrying implications for marginalised groups, including LGBT+ people, women and people from minority religions. And being prayed to or preached at while seeking a community service will be disastrous for public trust.

As they stand, the 'Faith New Deal' and the proposed 'faith compact' do not bode well for inclusive public services – let alone the principle of separating religion and state.

But they do bode well for a government keen to attract votes from faith groups.

If the government wants to demonstrate it truly cares about our local communities, and the organisations that work tirelessly to help local people in need, it must ensure its funding is available to all decent charities and community groups, both religious and non-religious alike. And it must ensure those groups prioritise serving people – not religious interests.

Image by Ch AFleks from Pixabay

The 2015 General Election

NSS: Don’t let NI faith schools fail pupils on reproductive rights

Requirement for RSE to reflect "religious principles" conflicts with neutral lessons on reproductive health in NI schools, NSS says.

Time for Church and state to part ways

Separating church and state would signal a forward-looking Britain committed to equality, inclusivity and freedom of religion or belief. National Secular Society CEO Stephen Evans explains why the NSS is backing a bill to disestablish the Church of England.

Bill to separate Church from state to be introduced in parliament

Private members' bill to disestablish the Church of England selected in ballot.

Wales Green Party drops pledge to ban non-stun slaughter

Members vote to monitor slaughter "without prejudice towards minority religious and cultural groups".

New bid made to remove bishop’s vote in Isle of Man parliament

House of Keys member behind bill says bishop should "go and get elected like the rest of us".

NSS joins campaigners calling for investigation of extremist charity sermons

Nine organisations call for action in open letter saying charities are promoting antisemitism and glorifying terrorism.

NSS “baffled” by anti-abortion protest against history talk

Christian group warns it will "actively" engage attendees of NSS talk on Victorian birth control – which aimed to reduce abortion.

NSS: Women in Jersey should have same access to abortion as Brits

Abortion in Jersey is expensive and usually only available up to 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Assisted dying on track to be legalised in Isle of Man

Access to assisted dying could become available as soon as 2025.

Beware religious threats to free speech, NSS warns UN rapporteur

Attempts to impose de facto blasphemy laws must be resisted, says NSS.