Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change

The time has come to rethink religion's public role in order to ensure equality and fairness for believers and non-believers alike, says a major new report launched by the National Secular Society.

The report says that Britain's "drift away from Christianity" coupled with the rise in minority religions and increasing non-religiosity demands a "long term, sustainable settlement on the relationship between religion and the state".

Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change has been sent to all MPs as part of a major drive by the Society to encourage policymakers and citizens of all faiths and none to find common cause in promoting principles of secularism.

It calls for Britain to evolve into a secular democracy with a clear separation between religion and state and criticises the prevailing multi-faithist approach as being "at odds with the increasing religious indifference" in Britain.

Terry Sanderson, National Secular Society president, said: "Vast swathes of the population are simply not interested in religion, it doesn't play a part in their lives, but the state refuses to recognise this.

"Britain is now one of the most religiously diverse and, at the same time, non-religious nations in the world. Rather than burying its head in the sand, the state needs to respond to these fundamental cultural changes. Our report sets out constructive and specific proposals to fundamentally reform the role of religion in public life to ensure that every citizen can be treated fairly and valued equally, irrespective of their religious outlook."

Read the report:

Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change

Add your endorsement to the manifesto for change

Add your endorsementComplete list of recommendations

Our changing society – Multiculturalism, secularism and group identity

1. The Government should continue to move away from multiculturalism and instead emphasise individual rights and social cohesion. A multi-faith approach should be avoided.

2. The UK is a secularised society which upholds freedom of and from religion. We urge politicians to consider this, and refrain from using "Christian country" rhetoric.

The role of religion in schools

Faith schools

3. There should be a moratorium on the opening of any new publicly funded faith schools.

4. Government policy should ultimately move towards a truly inclusive secular education system in which religious organisations play no formal role in the state education system.

5. Religion should be approached in schools like politics: with neutrality, in a way that informs impartially and does not teach views.

6. Ultimately, no publicly funded school should be statutorily permitted, as they currently are, to promote a particular religious position or seek to inculcate pupils into a particular faith.

7. In the meantime, pupils should have a statutory entitlement to education in a non-religiously affiliated school.

8. No publicly funded school should be permitted to prioritise pupils in admissions on the basis of baptism, religious affiliation or the religious activities of a child's parent(s).

9. Schools should not be able to discriminate against staff on the basis of religion or belief, sexual orientation or any other protected characteristics.

Religious education

10. Faith schools should lose their ability to teach about religion from their own exclusive viewpoint and the law should be amended to reflect this.

11. The Government should undertake a review of Religious Education with a view to reforming the way religion and belief is taught in all schools.

12. The teaching of religion should not be prioritised over the teaching of non-religious worldviews, and secular philosophical approaches.

13. The Government should consider making religion and belief education a constituent part of another area of the curriculum or consider a new national subject for all pupils that ensures all pupils study of a broad range of religious and non-religious worldviews, possibly including basic philosophy.

14. The way in which the RE curriculum is constructed by Standing Advisory Councils on Religious Education (SACREs) is unique, and seriously outdated. The construction and content of any subject covering religion or belief should be determined by the same process as other subjects after consultation with teachers, subject communities, academics, employers, higher education institutions and other interested parties (who should have no undue influence or veto).

Sex and relationships education

15. All children and young people, including pupils at faith schools, should have a statutory entitlement to impartial and age-appropriate sex and relationships education, from which they cannot be withdrawn.

Collective worship

16. The legal requirement on schools to provide Collective Worship should be abolished.

17. The Equality Act exception related to school worship should be repealed. Schools should be under a duty to ensure that all aspects of the school day are inclusive.

18. Both the law and guidance should be clear that under no circumstances should pupils be compelled to worship and children's right to religious freedom should be fully respected by all schools.

19. Where schools do hold acts of worship pupils should themselves be free to choose not to take part.

20. If there are concerns that the abolition of the duty to provide collective worship would signal the end of assemblies, the Government may wish to consider replacing the requirement to provide worship with a requirement to hold inclusive assemblies that further pupils' 'spiritual, moral, social and cultural education'.

Independent schooling

21. All schools should be registered with the Department for Education and as a condition of registration must meet standards set out in regulations.

22. Government must ensure that councils are identifying suspected illegal, unregistered religious schools so that Ofsted can inspect them. The state must have an accurate register of where every child is being educated.

Freedom of expression - Freedom of expression, blasphemy and the media

23. Any judicial or administrative attempt to further restrict free expression on the grounds of 'combatting extremism' should be resisted. Threatening behaviour and incitement to violence is already prohibited by law. Further measures would be an illiberal restriction of others' right to freedom of expression. They are also likely to be counterproductive by insulating extremist views from the most effective deterrents: counterargument and criticism.

24. Proscriptions of "blasphemy" must not be introduced by stealth, legislation, fear or on the spurious grounds of 'offence'. There can be no right to be protected from offence in an open and free secular society.

25. The fundamental value of free speech should be instilled throughout the education system and in all schools.

26. Universities and other further education bodies should be reminded of their statutory obligations to protect freedom of expression under the Education (No 2) Act 1986.

Religion and the law

Civil rights, 'conscience clauses' and religious freedom

27. We are opposed in principle to the creation of a 'conscience clause' which would permit discrimination against (primarily) LGBT people. This is of particular concern in Northern Ireland.

28. Religious freedom must not be taken to mean or include a right to discriminate. Businesses providing goods and services, regardless of owners' religious views, must obey the law.

29. Equality legislation must not be rolled back in order to appease a minority of religious believers whose views are out-of-touch with the majority of the general public and their co-religionists.

30. The UK Government should impose changes on the rest of the UK in order to comply with Human Rights obligations. Every endeavour should be made by to extend same sex marriage and abortion access to Northern Ireland.

Conscience 'opt-outs' in healthcare

31. Efforts to unreasonably extend the legal concept of 'reasonable accommodation' and conscience to give greater protection in healthcare to those expressing a (normally religious) objection should be resisted.

32. Conscience opt-outs should not be granted where their operation impinges adversely on the rights of others.

33. Pharmacists' codes should not permit conscience opts out for pharmacists that result in denial of service, as this may cause harm. NHS contracts should reflect this.

34. Consideration should be given to legislative changes to enforce the changes to pharmacists codes recommended above.

The use of tribunals by religious minorities

35. The legal system must not be undermined. Action must be taken to ensure that none of the councils currently in operation misrepresent themselves as sources of legal authority.

36. Work should be undertaken by local authorities to identify sharia councils, and official figures should be made available to measure the number of sharia councils in the UK to help understand the extent of their influence.

37. There needs to be a continuing review by the Government of the extent to which religious 'law', including religious marriage without civil marriage, is undermining human rights and/or becoming de facto law. The Government must be proactive in proposing solutions to ensure all citizens are able to access their legal rights.

38. All schools should promote understanding of citizenship and legal rights under UK law so that people – particularly Muslim women and girls – are aware of and able to access their legal rights and do not regard religious 'courts' as sources of genuine legal authority.

Religious exemptions from animal welfare laws

39. Laws intended to minimise animal suffering should not be the subject of religious exemptions. Non-stun slaughter should be prohibited and existing welfare at slaughter legislation should apply without exception.

40. For as long as non-stun slaughter is permitted, all meat and meat products derived from animals killed under the religious exemption should be obliged to show the method of slaughter.

41. In public institutions it should be unlawful not to provide a stunned alternative to non-stun meat produce.

Religion and public services

Social action by religious organisations

42. The Equality Act should be amended to suspend the exemptions for religious groups when they are working under public contract on behalf of the state.

43. Legislation should be introduced so that contractors delivering general public services on behalf of a public authority are defined as public authorities explicitly for those activities, making them subject to the Human Rights Act legislation.

44. It should be mandatory for all contracts with religious providers of publicly-funded services to have unambiguous equality, non-discrimination and non-proselytising clauses in them.

45. Public records of contracts with religious groups should be maintained and appropriate measures for monitoring their compliance with equality and human rights legislation should be put in place.

46. There should be an enforcement mechanism for the above, which would for example receive and adjudicate on complaints without complainants having to take legal action.

Hospital chaplaincy

47. Religious care should not be funded through NHS budgets.

48. No NHS post should be conditional on the patronage of religious authorities, nor subject directly or indirectly to discriminatory provisions, for example on sexual orientation or marital status.

49. Alternative funding, such as via a charitable trust, could be explored if religions wish to retain their representation in hospitals.

50. Hospitals wishing to employ staff to provide pastoral, emotional and spiritual care for patients, families and staff should do so within a secular context.

Institutions and public ceremonies

Disestablishment

51. The Church of England should be disestablished

52. The Bishops' Bench should be removed from the House of Lords. Any future Second Chamber should have no representation for religion whether ex-officio or appointed, whether of Christian denominations or any other faith. This does not amount to a ban on clerics; they would eligible for selection on the same basis as others.

Remembrance

53. The Remembrance Day commemoration ceremony at the Cenotaph should become secular in character. Ceremonies should be led by national or civic leaders and there should be a period of silence for participants to remember the fallen in their own way, be that religious or not.

Monarchy and religion

54. The ceremony to mark the accession of a new head of state should take place in the seat of representative secular democracy, such as in Westminster Hall and should not be religious.

55. The monarch should no longer be required to be in communion with the Church of England nor ex officio be Supreme Governor of the Church of England, and the title "Defender of the Faith" should not be retained.

Parliamentary prayers

56. We believe Parliament should reflect the country as it is today and remove acts of worship from the formal business of the House.

Local democracy and religious observance

57. Acts of religious worship should play no part in the formal business of parliamentary or local authority meetings.

Public broadcasting, the BBC and religion

58. The BBC should rename Thought for the Day 'Religious thought for the day' and move it away from Radio 4's flagship news programme and into a more suitable timeslot reflecting its niche status. Alternatively it could reform it and open it up to non-religious contributors.

59. The extent and nature of religious programming should reflect the religion and belief demographics of the UK.

Add your endorsement to the manifesto for change

Add your endorsementThe 2017 General Election

Mandated worship can never be inclusive

Church of England guidance which aims to promote an 'inclusive' form of collective worship in schools misses the point and highlights the need to stop imposing religion on children, says Alastair Lichten.

The Church of England, which is bizarrely still a state church in the only democracy in the world to mandate Christian worship in schools, has released new guidance for making directed worship "Inclusive", Invitational" and "Inspiring" (sic).

This comes amid significant questions over whether the requirement to hold collective worship is compliant with human rights, and legislative efforts to remove it. Meanwhile the government recently made the absurd suggestion that it would enforce the requirement. The C of E has been forced to concede it must provide inclusive alternatives to worship; the requirement is clearly unpopular; and church adherence among young people continues to shrivel.

The C of E's guidance is predominantly about the faith schools it runs, but the church makes no secret of its desire to influence all schools. It has lobbied strongly against any efforts to remove the collective worship requirement in any school. It often acts as if community ethos schools should be Christian by default. And it robustly promotes collective worship in non-faith schools under its influence.

The guidance has been seen in some places as a move towards a less "preachy", less exclusive approach. It advises against "strongly confessional lyrics", but stresses that the Christian nature of worship should not be watered down.

To its credit, the guidance states that "there should be no assumption of Christian faith in those present". It also says "care will be taken to ensure that the language used by those facilitating worship avoids assuming faith in all those participating".

But this goes against the C of E's track record of trying to treat schools as Christian religious communities. As highlighted in our recent report, Religiosity inspections: the case against faith-based reviews of state schools, the C of E promotes a robust and theologically centred approach to both collective worship and RE in schools.

As with many other social issues, the C of E is twisting itself in knots over collective worship. It has enough self-awareness to know that being too openly evangelical is not popular, but without some evangelism it risks seeming irrelevant.

If worship in schools were to be genuinely "Invitational" it would have to be entirely voluntary, an opt in activity that pupils could choose rather than an integral part of the school day. This isn't the approach the C of E is advocating.

Genuinely inclusive assemblies can also invite responses that may or may not involve worship, through a moment of silence where pupils can choose, rather than being directed, to pray or reflect. That would respect everyone's freedom of and from religion. Again, this is not what the C of E is advocating – and it speaks volumes.

The only freedom the church's guidance mentions is not the right to be free from imposition of worship, it is "freedom of those of different faiths and those who profess no religious faith to be present".

The guidance makes limited reference to the right to withdraw from collective worship, reflecting the C of E's limited regard for this right. There is no reference to inclusive alternatives, perhaps as the church only wants one 'invitation' on offer. It does nothing to address coercive practices in C of E faith schools which discourage withdrawal and marginalise those who do not wish to take part. Perhaps this is all part of the 'invitation'.

The current debate and developing case law surrounding collective worship should prompt the government to review its own outdated guidance, which currently states worship should include "reverence or veneration paid to a divine being or power".

But reforms and guidance which dance around the issue are not enough. Ultimately, requiring children to worship in school is incompatible with the right to freedom of religion and belief. Assemblies shouldn't impose religion on children. And that means the law that requires acts of worship should be removed from the statute book and replaced with a duty on schools to hold genuinely inclusive assemblies for all.

Image by Jaime Wiebel from Pixabay.

Faith universities are an anachronism

Churches continue to manage and govern several universities in the UK, enabling discrimination and creating tension between universities' academic purpose and the interests of those who control them, says Keith Sharpe.

This was originally published in Times Higher Education and is reprinted here with kind permission.

It is a little noticed fact that 15 universities in the UK are managed and governed by churches. To all intents and purposes these are faith universities.

They began in the 19th century as training colleges founded by the major churches to supply teachers for their schools. Over the subsequent decades, they developed other kinds of higher education provision across a range of disciplines and gradually became universities.

Despite this remarkable change in their activities and status, however, they remain tightly controlled by the churches. All of them still have religiously nominated governors – many reserve roles for bishops and archbishops – and that cohort almost always has a built-in majority over any non-religious governors.

Consider the University of Chester. The university council's membership must have a majority of "foundation members", defined as practising members of a church that is a member of the pan-Christian organisation Churches Together in Britain and Ireland. Furthermore, the majority of foundation members must be "communicant members of the Church of England". The lord bishop of Chester and the dean of Chester are automatic members, along with the university's vice-chancellor – who must also be a practising Christian.

In a similar way, the Roman Catholic Church dominates St Mary's University, Twickenham. The archbishop of Westminster and the Catholic Education Service nominate the majority of the governors between them.

In its articles of association, St Mary's declares that its purpose is "to advance education in such a manner as befits a Catholic foundation", and "the arbiter of what befits a Catholic foundation shall be the chair", who must be the archbishop of Westminster or a Catholic bishop nominated by the archbishop. Yet the Nolan standards of conduct in public life lay down that holders of public office must be under no obligation to organisations that might try to influence them. You might reasonably ask how any religious representative could possibly meet this standard. You might also ask how a requirement to appoint a religious representative is compatible with the Nolan principle of objectivity, which requires that decisions should be made on merit and without discrimination or bias.

Gaps in UK equality legislation make it legal for these faith universities to discriminate in the appointment of staff, up to and including the post of vice-chancellor, but this is certainly not fair or just. In practice, it means highly qualified applicants for posts in these universities are excluded solely because they lack a particular religious faith. The effort to preserve religious doctrine is at odds with the purpose of a university, which is to promote the development of human knowledge and understanding. And yet almost all the funding these institutions get comes from the public purse – unless and until their students repay their loans in full.

This issue is particularly troubling in light of signs that the Church of England plans to take the universities it controls in a regressive direction. In March 2020, the church published Faith in Higher Education – A Church of England vision, which declares that the universe is intelligible because it was created by a good God and that higher education is about using "our minds to explore and seek the renewal of all of God's creation". Education and wisdom are achieved by "aligning all our ways – our thinking, acting, belonging – with those of God", and the Bible "offers a panoramic vision of the creative action of God in the natural world".

These are partisan doctrinal assertions; they are not starting points for academic research and investigation in a contemporary university context. Even more worrying is the claim that subject content in all disciplines should be shaped by the tenets of Christian belief: "Sustained theological attention is needed on…the content of any particular discipline or field, the methodologies with which these are examined and interpreted, and the curriculum through which it is taught…We would not assume, for example, that subjects as diverse as law, business, nursing and media would remain uninfluenced by being located within an explicitly Christian narrative."

This statement is incompatible with a statement on the Office for Students' website, which rightly says that academic staff at English universities have the freedom to "question and test received wisdom" and "to put forward new ideas and controversial or unpopular opinions".

Faith universities are an anachronism and the religious privilege embedded in them should be ended. The management and governance of former teacher training colleges must reflect the diversified modern universities that they have become, serving a society that is much more secular-minded and multicultural than it was when they were founded.

Publicly funded institutions of higher education should be governed and managed in the public interest, not in the interest of churches and the dogmas they seek to promulgate.

Image: Grotesque at Chester Cathedral, via Wikicommons - user: Rock drum [CC BY-SA 3.0]

The drive for ‘religious literacy’ in the media would undermine press freedom

A parliamentary report has called for measures to promote 'religious literacy' in the media - including tighter regulation. Chris Sloggett says we should beware the risks of requiring journalists to tread on eggshells.

"We are calling for a fundamental shift in a media culture that is either too dismissive or disdainful of religion."

So say Yasmin Qureshi MP and the crossbench peer Elizabeth Butler-Sloss, on a recent report from a parliamentary group they lead, in PoliticsHome.

The report - the somewhat patronisingly titled 'Learning to listen', from the all-party parliamentary group on religion in the media - argues that there is a lack of 'religious literacy' in the media, this is a significant problem and measures should be taken to address it.

The report speaks of the importance of "shared values and social cohesion". Its authors also say they "entirely agree" that the media should be free to criticise beliefs. And there's no reason to doubt their sincerity. But the "fundamental shift" they propose would push a censorious pro-religious agenda on the press.

A particular concern is the report's recommendation that training providers should incorporate 'religious literacy' training into their qualifications. The APPG appears to consider religion an important enough subject to justify this treatment, but this is unconvincing. Should a journalist who has no interest in covering religious affairs be forced to care about them?

And what does this 'religious literacy' look like? At one point the report acknowledges that genuine religious literacy involves a critical understanding of religion's positive and negative impact. But a telling line arrives when the authors try to define the term.

"In practice," they say, "we think that religious literacy also incorporates respect for religion and belief as a valid source of guidance and knowledge to the majority of the world's inhabitants." Promoting 'respect' for religion - the ideas, not the people who hold them - is at odds with the principle that journalists should be free and willing to criticise all ideas as merited.

The report approvingly cites a submission which said "an assumption that society is secularised, religious beliefs are absurd and a problem and religious belief is in decline" represents "religious illiteracy". Elsewhere it says "religion is here to stay and a media that fails to recognise this will inevitably be out of touch". Much of the evidence it relies on comes from community groups and commentators with strongly pro-religious views.

So the call for greater 'religious literacy' is an endorsement of a pro-religious viewpoint, and embedding it in training courses for journalists would be a power grab. The report's recommendations for the broadcast media would have a similar impact: it says the current religious programming hours on the BBC should be protected and the remit of public service broadcasters redrafted to promote 'religious literacy'.

There are also signs of a power grab when the report calls on policy makers to look again at press regulation. And it makes one significant recommendation worthy of particular attention: that groups should be able to make complaints on the grounds of discrimination.

This was also a major point of contention when the press regulator Ipso decided to introduce guidance on the reporting of Islam and Muslims a couple of years ago. While these were being drawn up, in 2019, the regulator's outgoing chair described guidelines on discrimination as "the greatest issue Ipso has had to grapple with".

That year I expressed concern over the direction that Ipso's guidance might take. But when it came out last year, it was a balanced, fair and compassionate explanation of the relevance of clauses 1 (on accuracy) and 12 (on discrimination) of the editors' code.

For example, it told editors to ensure headlines were supported by the story beneath them (noting that this was why The Sun was found in breach of the code when it published the headline "1 in 5 Brit Muslims' sympathy for jihadis"). It told journalists to consider whether the fact someone was Muslim was relevant to the story before mentioning that detail. But it also made clear that an overly broad interpretation of the code would infringe on press freedom.

Ipso's decision not to ban discrimination against groups produced a swift backlash, particularly from several community groups. And there were echoes of this in a higher-profile furore a few months later.

In February a letter from more than 100 public figures to the BBC denounced an interview between BBC Woman's Hour presenter Emma Barnett and Zara Mohammed, the new leader of the Muslim Council of Britain. They called the interview "strikingly hostile", largely basing their criticism on the fact Barnett had asked questions about the number of female imams in Britain.

The hyper-scrutiny that followed this relatively unremarkable interview may well tempt some journalists to steer clear of such terrain in future, and to avoid asking religious leaders tough questions. Such offence-taking risks sending a very bad message about the principle that power should be held to account, and shutting down valid lines of questioning.

But the APPG's recommendation would turn similar culture wars into a formal process. It would hand a weapon to well-organised groups to shut down coverage they dislike. And though the report rightly acknowledges that diversity exists within religious groups, handing community leaders the power to bring such claims would disempower dissenters within their own communities.

Even if those claims were dismissed, they would deter prudent journalists from covering issues which may upset religious groups. And they could also prompt a counter-reaction, by incentivising other, perhaps less scrupulous, journalists who fancy a fight.

So the APPG's drive for 'religious literacy' in the press would require journalists to tread on eggshells. It would abandon the crucial principle that the press holds power to account, not vice versa. And it would give group leaders greater power to shut down criticism of their record on individual rights. It would be bad for social cohesion and for press freedom, and should be rejected.

Image by congerdesign from Pixabay.

The DfE must show leadership when religious hardliners turn on schools

The start of an investigation into the Batley Grammar affair raises questions over the government's willingness to ensure assertive religious voices don't dictate what happens in classrooms, says Stephen Evans.

This article is available in audio format, as part of our Opinion Out Loud series.

A few weeks ago, Batley Grammar School suspended a teacher who had showed a cartoon of the prophet Muhammad in a lesson, as protesters gathered outside its gates. The teacher was forced into hiding, and the case generated widespread publicity.

The school's priority seemed to be ensuring that loud voices in the local Muslim community weren't offended. This was also true of many public figures who took an interest in the case. Politicians and pressure groups lined up to denounce the use of a cartoon in a lesson. Often, they appeared more concerned about the use of a cartoon than the safety of a teacher and the prospect of mob rule dictating what could be taught in a school.

Now the academy trust behind the school has announced that an investigation has opened into the affair. This provides an opportunity to hear what happened in full, and to learn lessons. The trust has said the investigation will be led by an independent barrister with "significant education experience" and "no prior connection with the trust or any of its trustees or employees", which is encouraging.

However, the remit of the investigation may give cause for concern.

In a statement announcing the start of the inquiry, the trust said it would "examine how certain materials, which caused offence, came to be used" in the lesson. It didn't mention - at least explicitly - the school's treatment of the affected teacher. Are the offence-takers still framing the terms of the discussion?

The National Secular Society has sought clarification from both the trust and the Department for Education that the actions of the school are within the remit of the investigation. None has been forthcoming. The DfE simply said the specific terms of reference are a matter for the trust and investigator. This isn't good enough.

Fundamental principles are at stake. Cultural sensitivity can't be allowed to morph into censorship. Teachers must have the freedom to broaden pupils' horizons and encourage them to think critically. We can't allow decisions about the appropriateness of teaching resources to be influenced by offence taking, intimidation and threats.

The outcome of this investigation will have national implications. This episode has already sent a damaging message on teachers' ability to encourage critical thinking on culturally sensitive issues.

That could easily be forgotten if this is seen as a purely local issue, to be negotiated between assertive imams - who claim to speak for Muslims as a whole – and the individual school or trust.

So the government needs to show some leadership. But the Department for Education doesn't seem interested.

The trust has a legitimate interest in finding out what happened and taking recommendations. But it's also in the public interest to ensure the actions of the school are investigated. Feeling the heat from angry protests outside the school gates, the school issued an 'unequivocal apology' to the offended, deemed the resources to be 'completely inappropriate' and threw its teacher under the bus. If we take this imam's words at face value, the school even gave the protestors a role in drafting its statement. We need to know why this happened.

It's worth considering that a thorough investigation of the Batley affair may raise awkward questions for the government. The Batley affair is reminiscent of events at St Stephen's Primary School in east London in 2018. Then the school decided that girls under eight shouldn't wear hijabs in school, and young children shouldn't fast during Ramadan, on the basis that it was detrimental to their health and learning. Muslim pressure groups such as MEND and the Muslim Council of Britain became involved and the school was bombarded with emails in response, with some abusing and threatening violence against staff. The school was effectively forced to back down.

The Department for Education failed to support the school and said nothing on the row.

Arif Qawi, who was forced to quit as chair of governors following the affair, said he was "flabbergasted" at the DfE's silence. He wrote to the then education secretary Damian Hinds, pleading for help, saying that he and the school's head teacher Neena Lall had been "victims of absolutely vile personal abuse on social media platforms".

"This lack of support and weak attitude will be very detrimental to the nation's children," he said.

The DfE was also slow to respond when Muslim-led protesters objected to teaching about relationships and caused substantial disruption for primary schools in Birmingham in 2019. And when it issued guidance on relationships and sex education that year, it required schools to "take children's religious background into account" in their teaching.

We need to be sure that extremist elements within our communities are not impeding teachers' freedom and ability to prepare all pupils equally for life in modern Britain.

When protesters turn up outside the school gates and initiate harassment campaigns, schools shouldn't be left to fend for themselves. That leaves them at the mercy of the mobs and vulnerable to pressure from assertive, intolerant religious voices.

At least in Batley, the DfE issued a statement saying it was "never acceptable to threaten or intimidate teachers" and "schools are free to include a full range of issues, ideas and materials in their curriculum, including where they are challenging or controversial".

But condemnation only goes so far. The government has broader shoulders than any individual school or academy trust. So if ministers really want to uphold those principles, they should start by ensuring – if nobody else will – that an investigation considers the Batley episode in full.

Progress towards inclusive integrated education in NI is still too slow

The last few months have seen mixed successes in efforts, supported by the No More Faith Schools campaign, to move towards an integrated and inclusive education system in Northern Ireland.

In positive news the Department of Education has approved transformation proposals from two controlled (de facto Protestant) schools. Glengormley High School, in Newtonabbey in County Antrim, will become a new integrated school around September 2022. Carrickfergus Central Primary School will become a new integrated school around September 2021.

This follows the news last month that Seaview Primary, in Glenarm in County Antrim, has been the first Catholic maintained school approved to become integrated. The integration of these schools will bring together children from all religious backgrounds and none, and represent a significant step forward in a country where 93% of children are educated in de facto segregated schools.

Recent riots in several towns and cities across the country again highlighted the urgent need to bring different communities together, and schools are an effective way to do this. The people of NI understand the damages and inefficiencies of a segregated education system. Their demand for a better integrated alternative is loud and clear across all communities. Eighty-six per cent of parents at Carrickfergus, and 95% of parents at Seaview, supported the proposals.

Successful integration campaigns are worth celebrating. But the current education system, controlled by religious sectoral bodies, is unable to respond to these demands in anything more than a frustratingly inconsistent and piecemeal way.

Last month we reported that the Catholic St Mary's High School, Brollagh's transformation to integrated status had been rejected, despite 73% parental approval. It's now been joined by Ballyhackett Primary School, whose proposal was rejected, despite 69% of parents supporting it.

The principal of Ballyhackett PS, Grainne McIlvar, is quoted by the Integrated Education Fund (IEF) as saying: "We are devastated at the minister's decision, and bitterly disappointed." And that "this is a real blow in our efforts to educate children from different religious backgrounds together".

Meanwhile last month the consultation on a proposal by the OneSchool Global Network, asking for two of its Plymouth Brethren run private schools to become state funded, ended. The Education Authority in Northern Ireland has already indicated that it will not support the proposal.

This proposal is completely unsuitable, particularly given the extremely insular nature of the Plymouth Brethren. However, as long as the vast majority of schools are divided between the Protestant and Catholic communities, calls will increase for other minority religious groups to also be given their own schools, further fragmenting the education system.

The IEF and NI Council for Integrated Education (NICIE) have spotted one opportunity to make the case for change. They are currently calling on supporters to help highlight the important role of educating children together, in a consultation on the draft content of the European Union funded PEACE PLUS Programme (2021-2027). The programme, worth approximately €1bn, aims to promote the model for successful cross-community work. Breaking down the educational barriers must surely be a high priority.

The dominance of religious interests in the education system also goes beyond the official faith affiliation of schools.

A private member's bill proposed by Chris Lyttle, an Alliance MLA, is currently aiming to extend protection from religious discrimination to teachers. Again, the public overwhelmingly supports this change, but the divisions between different sectoral bodies, school types and approaches make it difficult.

Earlier this month the Raise Your Voice (against sexual harassment) coalition published an open letter calling for "the urgent introduction of compulsory, comprehensive and standardised relationships and sexuality education (RSE) in schools throughout Northern Ireland". This is a widely supported and overdue reform.

But the four largest churches have argued against this. They want to continue, through their sectoral bodies, ensuring that any RSE in schools fits with their religious ethos, particularly around information (or the lack thereof) on LGBT issues and contraceptives. Similar concerns have frustrated any efforts to bring in a modern pluralistic and non-proselytising religious education curriculum.

On all these issues the status quo puts the churches' interests ahead of those of Northern Irish society. But politicians should ensure schools across NI bring children together regardless of their families' religious identities.

This should be their priority as they approach a major independent review of education provision in NI. As I've previously argued, this is an excellent chance to take a stand for inclusive education. And with widespread public support for significant changes, the Stormont elections due in a year may also help to focus politicians' minds.

It is time for politicians from all communities to get serious about addressing the divisions and damage caused by the religious privilege inherent in NI's schools.

Faith groups have no business inspecting schools

Publicly funded school inspections which enable clerics to exert undue influence should have no place in a modern education system, argues Stephen Evans.

In a 21st century school system, should faith groups have the authority to inspect schools to determine whether the education they provide is sufficiently religious?

Most people will be familiar with England's school's inspectorate, Ofsted – or its equivalents in Wales and Scotland, Estyn and Education Scotland. These bodies inspect schools to provide information to parents, to promote improvement and to hold schools to account for the public money they receive.

But many people won't be aware that these aren't the only school inspections required by law.

Around one third of state-funded schools are faith schools. These schools are subject to additional inspections by religious bodies. The inspections are mandated by Sections 48 and 50 of the Education Act 2005. Their purpose is to evaluate the religious aspects of school life – denominational religious education, worship and the overall approach to promoting a religious ethos.

You might think that ongoing secularisation and the decline in the church‐going population would give rise to a corresponding decline in religion's involvement in state‐funded education. Instead, successive governments have bolstered religion's influence over state schooling by funding ever more faith schools.

Section 48 inspections are yet another mechanism for religious groups to exert control and influence children's education. They ensure organised religion remains a powerful force in education at both state and community levels. The inspections are used by faith bodies to pressure school leaders into ramping up the religiosity in schools. They influence decisions about the way in which education is provided and the environment in which it is delivered.

School leaders are more qualified and better placed than religious bodies to make these decisions. They understand their school communities better than anyone, and will usually be keenly aware that, unlike a church congregation, their pupil intake is far from religiously homogenous. Few families choose schools on the basis of their religious character, and many parents have little option other than a faith school. Yet religious inspection regimes coerce schools into acting like places of worship.

Now a new National Secular Society report has made the case for ending these inspections.

The report highlights numerous examples from school leaders of inspections being used to "sell the Church of England message", as one teacher puts it. The Catholic Church itself says the inspection process is intended to ensure schools "fulfil their mission of making Christ know". This is state-funded evangelism, plain and simple.

Take this Section 48 inspection report where a Catholic school in Birmingham is judged as "outstanding" for being "innovative in the way it uses the internet to evangelise"; gives staff, pupils and governors "many opportunities to pray"; and delivers relationships and sex education in a way that is "consistent with the teachings of the church".

In other words, the school is praised for inculcating children into the Catholic faith – rather than giving them the freedom to make up their own minds about their beliefs, or giving them the education they need about relationships and sex.

A key role of these 'religiosity inspections' is to assess the school's religious education. If religious education is a genuine academic subject, it should receive the same scrutiny as any other area of the curriculum.

But particularly in faith schools, religious education is too often an exercise in faith formation – a hangover from history more akin to confessional 'religious instruction'. The justification that Section 48 inspections are needed to assess RE provision tends to prove this point.

Teaching about religion or belief in schools should be objective, critically-informed and pluralistic. And like any other area of the curriculum, it should be inspected by Ofsted.

The purpose of education should be to develop critical faculties. But religiosity inspections are all about ensuring schools promulgate faith and impose acts of worship on pupils. This is all educationally inappropriate.

Even in an education system that includes faith schools, such extensive clerical meddling shouldn't be permitted, let alone funded with public money.

Yet the taxpayer stumps up £760,000 every year to fund inspections that serve the interests of religious groups, rather than pupils.

Britain is becoming more non-religious and more religiously diverse. It needs a secular education system that educates children of all faith and belief backgrounds together and enables children to make up their own minds about their beliefs.

And if we are going the cut the archaic connection between religion and state education, bringing an end to religion's role in inspecting schools would be a good place to start.

This blog is also published on Medium.

Regressive religious demands shouldn't hold sway over political decisions

Much of a pre-election letter from Scotland's Catholic bishops highlights the risks of allowing religious dogma to dictate public policy, says Stephen Evans.

With the Scottish parliamentary election approaching, Scotland's Catholic bishops have urged the faithful to play their part "in putting human life and the inviolable dignity of the human person at the centre of Scotland's political discourse".

In a pre-election 1,000 word pastoral letter, distributed via Scotland's 500 Catholic parishes, the bishops ask Catholic voters to give consideration to several key areas of concern, including family and work; freedom of expression, thought, conscience and religion; and Catholic schools.

The National Secular Society and the Catholic Church have been, unusually, aligned on the subject of free speech in Scotland in recent months. We were both among those who warned that the hate crime bill, which recently became law, would unreasonably restrict freedom of expression. Our lobbying helped to secure amendments which will go a long way toward protecting freedom of speech, particularly on religion.

So in principle I agree with the bishops that voters should caution politicians against imposing "unjust restrictions on free speech, free expression and freedom of thought, conscience and religion" - although naturally our opinions on what constitutes a reasonable limitation to religious freedom is likely to differ in many instances.

But too often the Catholic Church's teachings have been instrumental in undermining the rights of others. And much of the bishops' letter should serve as a reminder of the dangers of allowing religious dogma to drive political decisions.

For instance, the bishops call for Catholic schools to "be allowed to flourish". This is merely a self-interested plea for outdated sectarian schooling to persist. As well as enabling religious groups to proselytise with public money, religious schools foster segregation of children and undermine equality.

The bishops talk of the "right of parents to choose a school for their children which corresponds to their own convictions", saying public authorities have a duty to guarantee this parental right. This is true. But there is no obligation to provide funding for religious schools. If parents really want their child educated within their religious tradition, they can do that, but they shouldn't expect the state to support that choice with public money. A better use of public money is to provide schools that are open, inclusive and equally welcoming to all children whatever their religion and belief backgrounds.

If politicians want Scotland to be a tolerant, open, diverse country, then making sure children of all faith and belief backgrounds are educated together is an obvious starting point.

Meanwhile the church appeals to "human dignity" as it, predictably, makes the case against abortion rights and assisted dying.

On abortion, the church claims that "caring for the unborn and their mothers is a fundamental measure of a caring and compassionate society"; elsewhere it talks of "the duty to respect and protect the rights of the human embryo". Behind this rhetoric lies a wholly unreasonable demand – that women's control of their own bodies should be subject to a religious veto. As Oliver Kamm has written, the impact of this would violate "personal liberty, the exercise of conscience, women's rights and the sanctity of family life".

And the church's support for the status quo on assisted dying would mean people facing intolerable and incurable suffering would be unable to seek help to end their lives if they so choose. Decisions over assisted dying and reproductive rights should be based on medical ethics and personal autonomy, not religious dogma.

The church doesn't just have a limited view of 'dignity', which would justify the denial of rights to those who don't abide by its teachings. When it urges politicians to value the family, its website makes clear that this is based on "monogamous marriage between a man and a woman". This outdated vision excludes many Scots – most obviously those who are LGBT, or those who have children without being married.

At election time candidates or parties may be tempted to pander to religious interest groups in the hope of benefiting from a perceived block vote. The bishops' positions should be a reminder of the risks of doing that. If they want to promote the interests of Scottish society as a whole, Scotland's politicians should ensure regressive religious demands don't hold sway over their decisions.

Image: Diego Cervo/Shutterstock.com.

Women Leaving Islam: the rights of those who leave religion must be protected

The film Women Leaving Islam shows the risks facing those who stand up for the fundamental right to leave religion and the ongoing neglect of minorities within minorities in public life, says Helen Nicholls.

This article is available in audio format, as part of our Opinion Out Loud series.

In 2019 the British Social Attitudes survey revealed that more than half of the British population has no religion. Over the years many British people have chosen to leave their religion. For many, this is a gradual drift and the process is not necessarily difficult, especially if their families are not very religious. However, for others the process is not only painful, but also dangerous.

In the documentary Women Leaving Islam, six ex-Muslim women tell their stories. These are often harrowing. Halima Salat underwent female genital mutilation and was later subjected to an exorcism after trying to prevent a little girl from undergoing the same treatment. Fauzia Ilyas was prevented from seeing her daughter after her divorce. Fay Rahman describes an abusive childhood with a violent father. However, one of the most chilling parts of the programme comes right at the beginning:

"These interviews are limited to public activists as many other women originally interviewed didn't want their identities revealed or pulled out due to the personal risks involved."

This leaves us to wonder what stories the women who pulled out would have told and what might have happened to them if they had gone public.

The revelation that many interviewees were afraid to speak out publicly came as no surprise. At the NSS, we often hear from ex-Muslims, and count many amongst our membership. Some can never return to their countries of origin; others fear that they will be sent back. They are not only in danger in other countries. An ex-Muslim living in Britain once told me that he feared his family so much that if they came to his area he would move. One of our members told us that even in Britain he lives in fear, which takes the joy from his life. Another ex-Muslim living in a Muslim-majority country described the difficulties he faces every day. He did not ask us for anything but thanked me just for listening to his story.

In the documentary, Fay Rahman, who was brought up in London, describes how family members refused to intervene to prevent her father's violence. Eventually they turned on her when she called the police after he beat her badly. She left but could do nothing to help her younger siblings after the family did their best to cover up the abuse. At this point, she had not left Islam. Her offence was to involve outsiders. This echoes the pattern seen with sexual abuse within many religious organisations, where allegations have been handled internally to prevent outside interference. A public reluctance to discuss abuses within minority groups reinforces the silence.

Strict religious communities often go to great lengths to prevent members from leaving. This may take the form of educating children in illegal unregistered schools so they are unfit for life in modern Britain or keeping members in line with threats of shunning by the entire community, including family members. Ex-Muslims sometimes experience shunning.

In the documentary the YouTuber Mimzy Vidz describes family members saying they could not associate with her once she became public about her apostasy. However, what stands out in ex-Muslim narratives is the constant threat of violence. Even those with supportive families are in danger from extremists if they are public about having left Islam. Those wishing to visit family in Muslim-majority countries must also consider local laws on blasphemy and apostasy, which are punishable by death in some of them. Earlier this year, interviewee Zara Kay was arrested whilst visiting her native Tanzania on charges which appeared to be politically motivated. She has since been released and has returned to her home in Australia.

The right to freedom of religion includes the right to leave a religion. This right is not recognised in many Muslim-majority countries. However, it should be recognised in Britain both domestically and in foreign policy. The government has pledged to support Christians facing persecution abroad. It should also be willing to defend the rights of the non-religious.

There is no easy solution to the problems faced by ex-Muslims. As with other strict religious groups, the state cannot prevent religious people from shunning those who leave the faith although it can intervene when violence is threatened and, especially, when it is carried out. It can also offer some relevant services to support those affected. However, prevention is better than cure. Education on diversity must not neglect the minorities within minorities, who are often sacrificed on the altar of community relations.

The women interviewed on Women Leaving Islam were willing to risk their safety to speak up about their experiences. Politicians, journalists and human rights campaigners should be brave enough to lend their support. The risk they face is smaller: most fear allegations of racism and Islamophobia more than they fear violence. There are no easy answers, but nothing will be achieved if too many people in public life remain scared of the reasonable and necessary debate it should provoke.

There are many ex-Muslims willing to speak out. Some do so publicly, more will do so privately. We should be willing to listen to them.

Women Leaving Islam is a film by the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain, produced by Maryam Namazie and Gita Sahgal. You can watch it now on YouTube.

We must find the political will to end discriminatory school admissions

As families in England prepare to find out which primary schools their children will attend, Alastair Lichten says ending faith-based discrimination would make the admissions system fairer and simpler.

This Friday is primary school offer day in England. It comes in the middle of a few months where families of around 600,000 pupils across the UK will find out where they'll be attending school next academic year. There will be joy, relief and frustration for many.

And for large numbers the day will confirm they are the victim of the most pervasive form of legal faith-based discrimination in the UK. These families will miss out on places at their local schools thanks to faith schools' religious selection criteria.

The extent of religious discrimination in primary school admissions varies widely between different school types and individual schools. Estimates suggest 17% of primary school places in England are subject to religious selection, affecting well over 100,000 families a year. This includes people like Zoe from Wolverhampton, who told us via a petition: "I live right by a school (2 min walk) I would like my daughter to go to. But as we are not a religious family, I'm told she can't go there, and will now have to drive my child to school as the others are 5-10 minutes' drive."

These 17% of school places are not evenly distributed. Many faith schools operate a mix of open and selective admissions, while others can select up to 100% of their pupils based on religion. This discrimination affects people like Jonathan from Warrington who said: "My child is at the bottom of the list for our local primary school just because we are not part of any religious group."

Faith based admissions can lead to absurd demands being placed on parents, and it is well established that they lead to ethnic and socioeconomic selection. The complexity of admissions also confuses families and makes it harder to assess the impact of faith-based discrimination.

It's time politicians faced up to the damaging message that permitting religious discrimination sends to our children. For example, Charandeep from North London told us: "As a British born Sikh, the first time I felt excluded by society was when applying for primary schools. Despite having faith and regularly attending our local temple, my children were excluded."

Even among those with a range of views on faith schools, there is a lot of consensus over discriminatory admissions. Few people are willing to support religious selection. Even the faith school groups that do feel the need to obfuscate and dress this up in euphemism, such as claiming that pupils of all faiths are 'welcome to apply'. Various surveys in recent years have put support at only 15% or 17% among the public, and 18% among teachers.

The government promised a national review into school admissions in 2017 – but we've been waiting for it for almost four years. But rather than stand with the majority who support inclusive admissions, politicians continue to pander to the faith school lobby. Most recently, schools minister Nick Gibb signalled that the government is potentially open to removing the cap on religious discrimination in admissions to new academies. This would make it far easier to open faith schools with potentially total religious selection.

Politicians should go in the opposite direction. Ending faith schools, or at least the Equality Act exemptions which permit discriminatory admissions, would make the admissions system fairer and simpler. In the meantime, we need to call out discrimination for what it is and shame the politicians who give this practice their support or acquiescence.

Image: Andrew Heffernan/Shutterstock.com.

There is nothing new about cartoons which mock religion

Religious leaders have long feared irreverent drawings that could challenge their authority. We should remember that amid the latest effort to prevent the use of Muhammad cartoons, says Bob Forder.

In recent weeks there's been another furious response to the use of Muhammad cartoons – this time in an educational setting, at Batley Grammar School in Yorkshire.

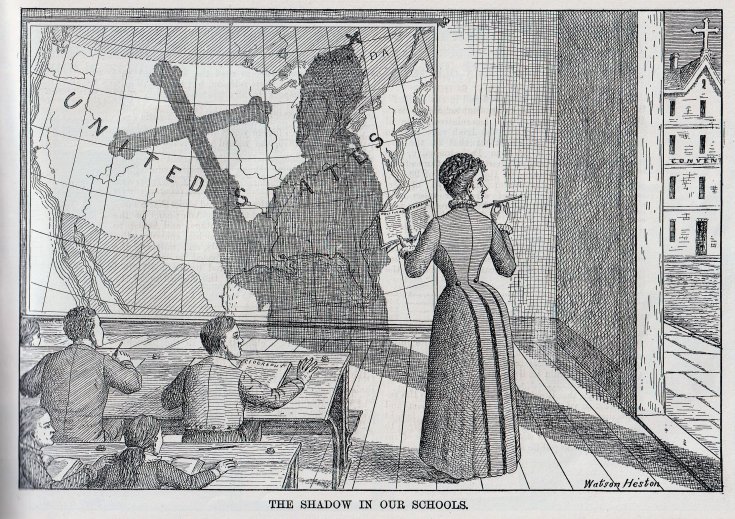

There is nothing new about cartoons being used as a device to poke fun at the religious. They have been a contentious source of blasphemy prosecutions and allegations ever since technical developments enabled their mass print production.

An early example is Leo Taxil's 'La Bible Amusante', which satirised what Taxil regarded as biblical inconsistencies and absurdities. G.W. Foote latched onto the cartoons in this book when he founded The Freethinker in 1881. He would undoubtedly have been encouraged by efforts to have Taxil's book banned in this country. From the outset Foote republished some of the cartoons as 'Comic Bible Sketches', although they were supplemented by others. More than anything else it was cartoons that made The Freethinker notorious and the reason the newspaper was such an immediate success in terms of its circulation.

At the same time, the leading US freethought newspaper The Truthseeker was publishing Watson Heston's cartoons (example below), which satirised biblical passages and celebrated US secularism and secular heroes like Thomas Paine. These were later collected together in books such as 'The Bible Comically Illustrated' and 'The Freethinkers' Pictorial Textbook'. These caused quite a rumpus, although little is known about Watson Heston.

Both D.M. Bennett (who founded The Truthseeker) and Foote were clear about the purpose of their cartoons. They reasoned that if you laugh at priests or ministers you can't take them seriously and they therefore lose authority. He had a point – and the same could be said for imams as for priests. I think this accounts in large part for the furious response in Batley.

Foote was eventually prosecuted for blasphemy (partly for the special 1882 Christmas number of The Freethinker, which was a cartoonists' feast). I include a copy of the cartoon from the front page (see main image). Other contents included a cartoon strip "A new life of Christ" and a particularly contentious cartoon "Moses getting a back view" with a quotation from Exodus "And it shall come to pass that I will put thee in a clift of the rock, and I shall take away my hand, and thou shalt see my back parts". The cartoon features a rather startled Moses staring at a pair of well-filled check trousers with a tear in the rear. None of this has me rolling around with laughter, but I can understand the furious response provoked in 1882 – and Foote's courage in publishing them.

Foote got a year in Holloway Gaol and was widely regarded as a hero and martyr in National Secular Society circles. It was this that ensured he became president when Charles Bradlaugh – the NSS's founder – resigned in 1890.

The Charlie Hebdo cartoons were published for similar reasons and are part of the same tradition.

There is, however, a significant difference between now and then. Those who objected in the 19th century were largely part of an elite which held a privileged position in society as a whole, embodied and supported by the established church. In some ways those demanding retribution in Batley can be considered amongst the least privileged in society and, for them, this is an issue tightly linked to their ethnicity and sense of identity.

This makes the issue far more complex and helps explain the disappointing woolly thinking, platitudes and fudge about the need to engage and listen that has crept in amongst what might loosely be termed the liberal left. But those condoning the dangerous and over-hasty behaviour of the Batley Grammar School governors and management really need to think again.

Secularism is a fundamental liberal democratic principle. The strength and success of liberal democracy rests not only on principles such as fair elections but also on the assumption that the political system accommodates all religions and beliefs with equal respect and access, apart from those intent on its overthrow.

A failure to understand this, and the freedom of speech it entails, is the real threat to us all, particularly the less privileged. Freedom of speech must entail a right to offend, however regrettable this might seem.

Sadly, the array of religious and community leaders (some self-appointed) assembled outside Batley Grammar School purport to represent a less privileged community. But giving in will simply enhance and protect these leaders' own status and position within their community, at others' expense, and run the risk of that community becoming further isolated from society at large.

The 2015 General Election

NSS urges nonreligious school to resist evangelism

Church of England youth evangelism scheme targets Jubilee High School in Surrey, which has no religious ethos.

US evangelicals exposed Welsh pupils to homophobia and creationism

First West Baptist Church say being gay is a form of "sexual immorality" and evolution is a lie

Test

Test

Don't extend religious privilege in parliament - end it

If you're vexed by Anglican clerics sitting as of right in our legislature deciding on the laws that affect us all, would you be assuaged by the idea of the bishops being joined by an assortment of imams, rabbis and priests?

No, I thought not.

But whenever the question of House of Lords reform comes up, the so called 'solution' of multifaith 'lords spiritual' is floated.

A recent survey of Church of England clergy found that almost half of them think the seats currently reserved for Anglican bishops in the House of Lords should be shared with other faith leaders.

This idea isn't new.

As long ago as 1970 the Archbishops' Commission on Church and State accepted the reduction of the number of bishops to 16 and proposed that the additional places be taken by other religious leaders.

In 1985 Conservative MP Richard Holt tabled an amendment to reduce their numbers to 14. Holt's plan involved replacing nine of the Church of England's bishops with representatives from other faith groups.

Then, in 1999, a report from The Royal Commission on the Reform of the House of Lords suggested the second chamber should have fewer Church of England peers to allow for more non-Christian representatives and other Christian denominations.

In 2011, a paper produced by the Conservative Christian Fellowship called for a "broad bench of Lords Spiritual", saying there was a "strong argument that our legislature would benefit from the wisdom of leaders of Baptist, Catholic, Methodist and black-led congregations".

The Woolf Institute's Commission on Religion and Belief in Public Life also published a report in 2013 which called for the representation of religion in the House of Lords to be reformed to "give voice to a greater variety of religious voices".

That support for a multifaith arrangement should come from within the Church of England itself isn't surprising. They know the game is up. In a country which even they concede can no longer be called Christian, their unique privileges are increasingly hard to justify. They know that their only real hope of retaining privileged political influence is to share the privilege around a bit.

Under the present arrangement, 26 Anglican bishops sit as legislators in the House of Lords by right of their position within the established Church.

This situation is unique in the democratic world. Iran is the only other country that provides seats as of right for clerics in its national legislature. The bishops' role in the House of Lords dates back to the feudal and medieval days of the 14th century – and is clearly unfit for a 21st century democracy.

Reform is long overdue. But a multifaith approach is fundamentally flawed and entirely unworkable.

On point of principle, why should religious groups enjoy preferential and automatic status in the country's legislature? There's no sound rationale for providing any distinct explicit representation for religious bodies in a modern, democratic chamber.

It is sometimes argued that the bishops' bench helps to maintain a space for religion in public life. But it's not clear why any special interest group should have a special space carved out for them. Religion is well equipped to compete just fine in the marketplace of ideas without a leg up.

The aspiration to make the House of Lords representative of the diverse beliefs and perspectives within the UK is sound. But under the current appointments system, this pluralism can be achieved by ensuring appointments reflect the UK's diversity in all its forms. Religious leaders can and have been appointed to the House of Lords through the existing appointments process. Such appointments should be on merit rather than as of right.

And it's worth noting that many temporal peers are religious – a much higher proportion than in the country, partly because of their greater average age. Many use their position to advocate for their faith. Religious interests are very well served in parliament without the need for special seats to be 'reserved'.

It has been suggested that religious leaders add value by bringing a moral dimension into parliamentary proceedings. This idea is as outdated as it is offensive. Religious leaders aren't the moral compass of the country. Quite the contrary, considering the public's opinion on issues ranging from same-sex marriage to assisted dying. Ordinary members of the House, whether religious or nonreligious, are just as able to bring ethical, moral, spiritual or philosophical perspectives into legislative deliberations.

And there certainly doesn't seem to be any desire amongst the public to have religious representatives automatically appointed to the second chamber. A 2021 YouGov survey found only 16% of British people believe bishops should be entitled to a seat in the House of Lords. It's hard to see that support rising if a collection of other faith leaders were to join them.

A multifaith approach to the lords spiritual would pose significant practical problems, too.

The question of which faith communities would be represented, and then identifying and selecting individuals who could legitimately represent those faith communities, would be both extremely difficult and highly divisive.

Unlike the Church of England, many denominations and faiths don't have a hierarchical structure. There is no supreme governing body in Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism or Islam. Which schools of thought would be represented and who would represent them? Would Ahmadis, who are considered non-Muslims by many mainstream Muslims, be represented, too?

The Chief Rabbi may be the rabbinical authority of the Orthodox sector, but his authority isn't recognised by the Reform Synagogues or by other congregations. Canon law doesn't even permit Roman Catholic priests to be members of secular legislative bodies, so would Catholic representation need to be undertaken by lay Catholics? Would Mormons and Jehovah's Witnesses, as Christian denominations, be treated on an equal footing with others? Would Nonconformists, Pagans and Humanists get a seat at the table? Would their consciences even allow them?

The whole concept of multifaith lords spiritual is a non-starter. Our democracy shouldn't be organised along the lines of Radio 4's Thought for the Day.

Removing seats 'as of right' for religious leaders is a more sensible, suitable and sustainable approach for a modern democracy.

Local authorities in Scotland are leading the way here by removing voting privileges of the religious representatives they are required by law to appoint to their education committees. The next step is surely to remove the obligation to appoint them in the first place. The same goes for the bishops in the Palace of Westminster.

Reserving a special role in policymaking for representatives of religious institutions runs counter to principles of equality. And this is the principle that should guide Lords reform. Religion should take its place alongside all other special interest groups and lobby through the same democratic channels.

People of all faiths and none should be encouraged to participate in our democracy, but it should be on the basis of equality rather than privilege.

Image: Roger Harris, Wikimedia Commons

Tribunal: GP’s evangelism of teenage patient was misconduct

Christian doctor reportedly clasped vulnerable teenage patient's hands in prayer and gave him a bible

Schools targeted in £3 million CofE child evangelism initiative

Church of England scheme to see youth ministers in Guildford running "worship events" in state schools, including a nonreligious school

Edinburgh Council ends religious reps’ voting powers

Decision to end voting privileges for unelected religious appointees at City of Edinburgh Council welcomed by NSS

More than half of clergy think CofE establishment needs review

Nearly 12% of priests support disestablishment, survey finds

Government awards £2.2m grant to homophobic and misogynistic mosque

Grant is paused and investigation launched following NSS concerns

UN resolution claims damaging holy books violates international law

UK efforts to introduce "more balanced language" were rejected