‘Inclusive language’ in the army is meaningless without inclusive culture

Posted: Mon, 8th Nov 2021 by Megan Manson

The Armed Forces must dismantle their institutional Christian privilege if they are truly committed to inclusivity, says Megan Manson.

This article is available in audio format, as part of our Opinion Out Loud series.

The Ministry of Defence has recently released an 'Inclusive Language Guide' (pictured). The guide promotes "using words that refer to everyone and avoiding words that exclude or offend".

On the face of it, the section on "Religion and Belief" looks promising. It offers sensible advice, such as not assuming a person's religion from their name or appearance, or their dietary preferences from their religion.

It's also focused on nonreligious beliefs. This is refreshing; nonreligious people are all too often neglected in conversations about religion or belief inclusion. The guide suggests, for example, using the term 'first name' instead of 'Christian name', and dropping the archaic term "morning prayers" for morning meetings.

This will no doubt be well-received by many nonreligious people in Defence – a demographic which is growing rapidly. The percentage of members of the Armed Forces who say they have no religion has shot up from less than 10% in 2007 to 34% in 2021.

But will a guide on speech truly make the army more inclusive of people of all faiths and none?

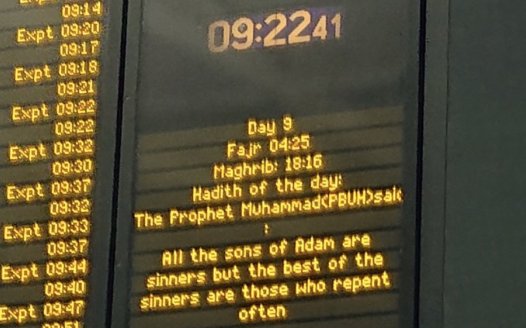

The Inclusive Language Guidance suggests the army is aware that prayers can be divisive and alienating for those who don't share in that tradition. It is therefore strange that while the guidance advises avoiding the word 'prayer' to refer to morning meetings, little has been done to address the actual prayer and religious services that are an inescapable part of life in Defence.

The Queen's Regulations for the Army (QRs), which set out the policy and practice of the army, were recently updated to specify that soldiers may not be compelled to attend acts of religious observance against their wishes. But this is negated by another clause in the regulations stating commanders may order a parade that includes a religious service which soldiers are expected to attend. In other words, soldiers who don't wish to pray must stand by silently while their comrades take part in the invariably Christian ceremony.

Such parades may include acts of remembrance, important occasions for all serving in Defence. While the Army General Administrative Instructions state that acts of remembrance should be "inclusive" and "separate religious elements from those that pay tribute to the fallen", in practice Christian prayers are still incorporated seamlessly into the proceedings with little separation.

The only way to avoid the religious parts is to not attend at all – and that is neither a realistic nor desirable option for personnel. Regardless of religion or belief, all soldiers want to take a full and active part in their unit's act of remembrance – but how can they do so when it is an act of worship?

Christian acts of worship pepper army life far beyond remembrance services. Units have their own 'corps collects', or prayers which mentions the unit. Army chaplains may be called upon to bless flags and ships. And 'passing out' parades for new soldiers may incorporate a Christian blessing, such as this one held by the Army Foundation College in February.

The only way to make military events truly inclusive of non-Christians is to remove Christian rituals from official proceedings, and so put Christianity on the same footing as all other religions and beliefs.

Another area of army life where Christian privilege is particularly acute is chaplaincy. Only ministers of a select group of eight 'sending churches', all Christian, may be chaplains (or 'padres') of regular army units.

When it comes to other religions, the Armed Forces have appointed religious leaders from the Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim and Sikh faiths to act as "advisers on matters specific to those faith groups", according to its guidance on religion or belief. It says action "is being taken to appoint civilian Chaplains from the faiths other than Christian most represented within the Armed Forces."

But there is no equivalent 'chaplain' specifically for the nonreligious. The guide says: "Should non-religious personnel in the Armed Forces wish to discuss their beliefs or problems with someone other than chaplains, there are a wide range of non-religious organisations which provide support and advice, including social workers, doctors and other professionals."

In other words, personnel who require nonreligious pastoral support are told that the army will not help them and they must go elsewhere.

According to the Army's recruitment page, chaplains "join the Army as a Captain earning £48,999." It hardly seems inclusive to offer such a prestigious and well-paid role only to Christians for the benefit of Christians, and nothing at all for the nonreligious.

And in addition to chaplains, the army permits an evangelical Christian group, The Soldiers' and Airmen's Scripture Readers Association (SASRA), unfettered access to "to share the gospel within the gated communities where the Army and the RAF are based". SASRA states its charitable objects as "to spread the saving knowledge of Christ among the personnel of HM forces in any part of the world." In other words, SASRA has a specific proselytising agenda.

Christian privilege in the army not only adversely affects nonreligious personnel and those who belong to minority faiths. It also impacts soldiers who are LGBT.

The 'sending churches' include denominations notorious for their anti-LGBT views, including the Free Church of Scotland, Elim Pentecostal Church and the Salvation Army. As military chaplains are required to "set forth God's word at all times" according to the Royal Army Chaplains' Department, what does this mean for gay soldiers who come to the chaplain with relationship problems, for example? Will they receive impartial and non-judgmental counselling if the chaplain sees their lifestyles as sinful?

Then there is the issue of same-sex marriages on military premises. Those who wish to marry on barracks have no option but the military chapel – which is largely under the control of the sending churches, most of which object to same-sex marriage.

As a result, while there are 190 military chapels in England and Wales registered for marriages, there has only been one gay wedding in a military chapel since same-sex marriage was legalised in 2014. Because there are no secular provisions for weddings on military sites, gay personnel have no meaningful options but to marry on a civilian site.

There are some encouraging signs of policy change that may indicate the army is waking up to the problems caused by its Christian bias.

Previously, QRs in effect make it impossible for atheists to become commanding officers, because the regulations imposed a duty on commanding officers to "encourage religious observance by those under their command" and to "set a good example in this respect". The QRs also required soldiers to get permission to change religion and said the "reverent observance" of religion in the armed forces is of the "highest importance".

Following long campaigning efforts from armed forces members, the QRs have now thankfully been recently revised to remove these unfair and illiberal requirements from the regulations.

The Armed Forces are clearly concerned about inclusivity, and over the years they have made many changes to make themselves more welcoming to all.

But it's also clear Christianity still holds a disproportionate sway over what is an increasingly irreligious and religiously-diverse army. If our Armed Forces are sincere in their desire to be welcoming to all, inclusive language is not enough – bold action is needed to ensure personnel of all religions and none are treated equally and fairly.

With special thanks to Lt Col (Retd) Laurence Quinn for his contributions.

Lt Col Quinn has produced two reports on the issue of inclusion of the nonreligious in the army; you can read them here and here.

What the NSS stands for

The Secular Charter outlines 10 principles that guide us as we campaign for a secular democracy which safeguards all citizens' rights to freedom of and from religion.