Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change

The time has come to rethink religion's public role in order to ensure equality and fairness for believers and non-believers alike, says a major new report launched by the National Secular Society.

The report says that Britain's "drift away from Christianity" coupled with the rise in minority religions and increasing non-religiosity demands a "long term, sustainable settlement on the relationship between religion and the state".

Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change has been sent to all MPs as part of a major drive by the Society to encourage policymakers and citizens of all faiths and none to find common cause in promoting principles of secularism.

It calls for Britain to evolve into a secular democracy with a clear separation between religion and state and criticises the prevailing multi-faithist approach as being "at odds with the increasing religious indifference" in Britain.

Terry Sanderson, National Secular Society president, said: "Vast swathes of the population are simply not interested in religion, it doesn't play a part in their lives, but the state refuses to recognise this.

"Britain is now one of the most religiously diverse and, at the same time, non-religious nations in the world. Rather than burying its head in the sand, the state needs to respond to these fundamental cultural changes. Our report sets out constructive and specific proposals to fundamentally reform the role of religion in public life to ensure that every citizen can be treated fairly and valued equally, irrespective of their religious outlook."

Read the report:

Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change

Add your endorsement to the manifesto for change

Add your endorsementComplete list of recommendations

Our changing society – Multiculturalism, secularism and group identity

1. The Government should continue to move away from multiculturalism and instead emphasise individual rights and social cohesion. A multi-faith approach should be avoided.

2. The UK is a secularised society which upholds freedom of and from religion. We urge politicians to consider this, and refrain from using "Christian country" rhetoric.

The role of religion in schools

Faith schools

3. There should be a moratorium on the opening of any new publicly funded faith schools.

4. Government policy should ultimately move towards a truly inclusive secular education system in which religious organisations play no formal role in the state education system.

5. Religion should be approached in schools like politics: with neutrality, in a way that informs impartially and does not teach views.

6. Ultimately, no publicly funded school should be statutorily permitted, as they currently are, to promote a particular religious position or seek to inculcate pupils into a particular faith.

7. In the meantime, pupils should have a statutory entitlement to education in a non-religiously affiliated school.

8. No publicly funded school should be permitted to prioritise pupils in admissions on the basis of baptism, religious affiliation or the religious activities of a child's parent(s).

9. Schools should not be able to discriminate against staff on the basis of religion or belief, sexual orientation or any other protected characteristics.

Religious education

10. Faith schools should lose their ability to teach about religion from their own exclusive viewpoint and the law should be amended to reflect this.

11. The Government should undertake a review of Religious Education with a view to reforming the way religion and belief is taught in all schools.

12. The teaching of religion should not be prioritised over the teaching of non-religious worldviews, and secular philosophical approaches.

13. The Government should consider making religion and belief education a constituent part of another area of the curriculum or consider a new national subject for all pupils that ensures all pupils study of a broad range of religious and non-religious worldviews, possibly including basic philosophy.

14. The way in which the RE curriculum is constructed by Standing Advisory Councils on Religious Education (SACREs) is unique, and seriously outdated. The construction and content of any subject covering religion or belief should be determined by the same process as other subjects after consultation with teachers, subject communities, academics, employers, higher education institutions and other interested parties (who should have no undue influence or veto).

Sex and relationships education

15. All children and young people, including pupils at faith schools, should have a statutory entitlement to impartial and age-appropriate sex and relationships education, from which they cannot be withdrawn.

Collective worship

16. The legal requirement on schools to provide Collective Worship should be abolished.

17. The Equality Act exception related to school worship should be repealed. Schools should be under a duty to ensure that all aspects of the school day are inclusive.

18. Both the law and guidance should be clear that under no circumstances should pupils be compelled to worship and children's right to religious freedom should be fully respected by all schools.

19. Where schools do hold acts of worship pupils should themselves be free to choose not to take part.

20. If there are concerns that the abolition of the duty to provide collective worship would signal the end of assemblies, the Government may wish to consider replacing the requirement to provide worship with a requirement to hold inclusive assemblies that further pupils' 'spiritual, moral, social and cultural education'.

Independent schooling

21. All schools should be registered with the Department for Education and as a condition of registration must meet standards set out in regulations.

22. Government must ensure that councils are identifying suspected illegal, unregistered religious schools so that Ofsted can inspect them. The state must have an accurate register of where every child is being educated.

Freedom of expression - Freedom of expression, blasphemy and the media

23. Any judicial or administrative attempt to further restrict free expression on the grounds of 'combatting extremism' should be resisted. Threatening behaviour and incitement to violence is already prohibited by law. Further measures would be an illiberal restriction of others' right to freedom of expression. They are also likely to be counterproductive by insulating extremist views from the most effective deterrents: counterargument and criticism.

24. Proscriptions of "blasphemy" must not be introduced by stealth, legislation, fear or on the spurious grounds of 'offence'. There can be no right to be protected from offence in an open and free secular society.

25. The fundamental value of free speech should be instilled throughout the education system and in all schools.

26. Universities and other further education bodies should be reminded of their statutory obligations to protect freedom of expression under the Education (No 2) Act 1986.

Religion and the law

Civil rights, 'conscience clauses' and religious freedom

27. We are opposed in principle to the creation of a 'conscience clause' which would permit discrimination against (primarily) LGBT people. This is of particular concern in Northern Ireland.

28. Religious freedom must not be taken to mean or include a right to discriminate. Businesses providing goods and services, regardless of owners' religious views, must obey the law.

29. Equality legislation must not be rolled back in order to appease a minority of religious believers whose views are out-of-touch with the majority of the general public and their co-religionists.

30. The UK Government should impose changes on the rest of the UK in order to comply with Human Rights obligations. Every endeavour should be made by to extend same sex marriage and abortion access to Northern Ireland.

Conscience 'opt-outs' in healthcare

31. Efforts to unreasonably extend the legal concept of 'reasonable accommodation' and conscience to give greater protection in healthcare to those expressing a (normally religious) objection should be resisted.

32. Conscience opt-outs should not be granted where their operation impinges adversely on the rights of others.

33. Pharmacists' codes should not permit conscience opts out for pharmacists that result in denial of service, as this may cause harm. NHS contracts should reflect this.

34. Consideration should be given to legislative changes to enforce the changes to pharmacists codes recommended above.

The use of tribunals by religious minorities

35. The legal system must not be undermined. Action must be taken to ensure that none of the councils currently in operation misrepresent themselves as sources of legal authority.

36. Work should be undertaken by local authorities to identify sharia councils, and official figures should be made available to measure the number of sharia councils in the UK to help understand the extent of their influence.

37. There needs to be a continuing review by the Government of the extent to which religious 'law', including religious marriage without civil marriage, is undermining human rights and/or becoming de facto law. The Government must be proactive in proposing solutions to ensure all citizens are able to access their legal rights.

38. All schools should promote understanding of citizenship and legal rights under UK law so that people – particularly Muslim women and girls – are aware of and able to access their legal rights and do not regard religious 'courts' as sources of genuine legal authority.

Religious exemptions from animal welfare laws

39. Laws intended to minimise animal suffering should not be the subject of religious exemptions. Non-stun slaughter should be prohibited and existing welfare at slaughter legislation should apply without exception.

40. For as long as non-stun slaughter is permitted, all meat and meat products derived from animals killed under the religious exemption should be obliged to show the method of slaughter.

41. In public institutions it should be unlawful not to provide a stunned alternative to non-stun meat produce.

Religion and public services

Social action by religious organisations

42. The Equality Act should be amended to suspend the exemptions for religious groups when they are working under public contract on behalf of the state.

43. Legislation should be introduced so that contractors delivering general public services on behalf of a public authority are defined as public authorities explicitly for those activities, making them subject to the Human Rights Act legislation.

44. It should be mandatory for all contracts with religious providers of publicly-funded services to have unambiguous equality, non-discrimination and non-proselytising clauses in them.

45. Public records of contracts with religious groups should be maintained and appropriate measures for monitoring their compliance with equality and human rights legislation should be put in place.

46. There should be an enforcement mechanism for the above, which would for example receive and adjudicate on complaints without complainants having to take legal action.

Hospital chaplaincy

47. Religious care should not be funded through NHS budgets.

48. No NHS post should be conditional on the patronage of religious authorities, nor subject directly or indirectly to discriminatory provisions, for example on sexual orientation or marital status.

49. Alternative funding, such as via a charitable trust, could be explored if religions wish to retain their representation in hospitals.

50. Hospitals wishing to employ staff to provide pastoral, emotional and spiritual care for patients, families and staff should do so within a secular context.

Institutions and public ceremonies

Disestablishment

51. The Church of England should be disestablished

52. The Bishops' Bench should be removed from the House of Lords. Any future Second Chamber should have no representation for religion whether ex-officio or appointed, whether of Christian denominations or any other faith. This does not amount to a ban on clerics; they would eligible for selection on the same basis as others.

Remembrance

53. The Remembrance Day commemoration ceremony at the Cenotaph should become secular in character. Ceremonies should be led by national or civic leaders and there should be a period of silence for participants to remember the fallen in their own way, be that religious or not.

Monarchy and religion

54. The ceremony to mark the accession of a new head of state should take place in the seat of representative secular democracy, such as in Westminster Hall and should not be religious.

55. The monarch should no longer be required to be in communion with the Church of England nor ex officio be Supreme Governor of the Church of England, and the title "Defender of the Faith" should not be retained.

Parliamentary prayers

56. We believe Parliament should reflect the country as it is today and remove acts of worship from the formal business of the House.

Local democracy and religious observance

57. Acts of religious worship should play no part in the formal business of parliamentary or local authority meetings.

Public broadcasting, the BBC and religion

58. The BBC should rename Thought for the Day 'Religious thought for the day' and move it away from Radio 4's flagship news programme and into a more suitable timeslot reflecting its niche status. Alternatively it could reform it and open it up to non-religious contributors.

59. The extent and nature of religious programming should reflect the religion and belief demographics of the UK.

Add your endorsement to the manifesto for change

Add your endorsementThe 2017 General Election

Time for an anthem we can all sing with sincerity

The religious and monarchical God Save the King should make way for something that the whole country can sing along to, says Stephen Evans.

Speaking in 2020 the new prime minister Rishi Sunak described the UK as a "secular country".

Rishi was right in the sense that British people, irrespective of their personal religious beliefs, are overwhelmingly secularist in their outlook and attitudes.

We are also one of the world's least religious countries. The latest British Social Attitudes survey revealed a significant and long term decline in the proportion of people who identify with Christianity along with a substantial increase in those with no religious affiliation, and a steady increase in those belonging to non-Christian faiths.

It also found very low confidence in religious organisations, but tolerance of religious difference. The election of a Muslim London mayor and the appointment of the UK's first Hindu prime minister is testament to that.

Our constitutional privileging of Christianity is therefore looking increasingly absurd. The continued existence of an established church in a modern pluralistic, multifaith and increasingly secular democracy is unsustainable. For example, it's nonsense that Rishi Sunak – a Hindu – is, as prime minister, responsible for advising King Charles on ecclesiastical appointments to the Church of England.

If Britain is to become a truly a secular country, we need to reflect this reality by uncoupling religion from the state and ceremonial occasions.

So isn't it time we also reconsidered our national anthem?

God Save the King was adopted more than 250 years ago – making it yet another relic of a time when adherence to the state religion was expected and assumed. That time has long disappeared into the past. The anthem should, too.

Officially God Save the King is the national anthem of the United Kingdom, but it has also been synonymous with England. In 2010, the Commonwealth Games Council for England polled the public to decide the athletic team's anthem. Three options were put forward. The clear winner was Blake's Jerusalem with 52% of the vote compared to Land of Hope and Glory with 32%. God Save the Queen came in a distant third with just 12%. England's cricket and rugby teams have also since switched to Jerusalem.

God Save the Queen King is essentially a sycophantic hymn, invoking a supreme being that many people don't believe in (God) to save an individual born into a position of privilege (the King). Almost all other international anthems are about the countries themselves, or the people, not their rulers.

A study by the Pew Research Center in 2017 asked citizens of 13 countries whether being Christian was important to national identity. Just 18% of UK citizens said it was. People on the right of the ideological spectrum were more likely to view religion as very important to nationality.

But in today's diverse Britain, isn't it inherently divisive for notions of national identity and belonging to be tied up with religion? This isn't something we can build a collective identity around.

Non-Christian political, civic and religious leaders, sports personalities representing their country, and perhaps many of us who feel little affinity with God or monarchy, face a difficult decision whether to pay lip service to the anthem and sing along, or not – and run the risk of criticism for not showing sufficient 'respect'. I consider myself a patriot, but God Save the King isn't something I can sing with authenticity. So, I don't.

These things matter. Equality, integration, social cohesion and a sense of shared citizenship is made so much harder when national identity is so intrinsically tied to religion. Wouldn't it be better to build a more inclusive and authentic national identity, rather than cleave to something vaguely Christian, increasingly meaningless and so obviously exclusionary?

It's not as if God Save the King is universally loved. During the Queen's Jubilee in 2012, YouGov asked people how they felt about the anthem. An overwhelming number of people said they didn't like it. Participants not in favour of the anthem used a slew of derisory 'd' words to describe how they felt about it: 'dull', 'depressing', 'dour', 'dull', 'downbeat' and (most popular) 'a dirge'. Almost half of 18-24 year olds don't even know the first verse.

If we are to end the pernicious pretence of the United Kingdom being a 'Christian Country', our anthem needs a rethink. Something more secular would allow all citizens to express themselves with sincerity, whatever their religious beliefs.

Let's not let tradition stand in the way of having something we can all sing along to. Suggestions on a postcard please…

Image: LA(Phot) Simmo Simpson, OGL v1.0OGL v1.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Child evangelism isn’t charitable

Religious organisations with a focus on evangelising and converting children are exploitative and potentially harmful. They shouldn't be enabled by our charity or education systems, says Megan Manson.

"Sinners by nature and practice, children stand guilty and condemned before God."

"We need faithfully and tenderly to warn children of eternal separation and punishment."

"We will not coldly announce, 'If you go on in your sin, you will go to hell.' Yes, we will teach this solemn truth, but with tenderness and entreaty."

These sinister statements are from a pamphlet entitled "A manual on the evangelism of children". They tap into children's deepest fears: separation from loved ones and inescapable punishment.

Many would consider telling children they are sinners destined for hell callous and cruel, if not downright abusive. Yet this pamphlet is produced by a registered charity: Child Evangelism Fellowship (CEF). Its official charitable objects are to advance "the evangelical Christian faith and in particular child evangelism".

CEF is explicit about why it is obsessed with preaching to children: "Children are open to anything! They are sensitive, vulnerable, impressionable…If we have the opportunity to leave a lasting impression on children, because they are more open, then we must do all we can to reach them with the Gospel. The formative years pass very quickly."

Or as it puts more succinctly: "Win a child and you win an adult". In other words, children are far easier to effectively convert to Christianity than adults. And in a society where religious affiliation is undergoing rapid decline, it's easy to see why religious groups are scrambling to access the easiest people they can convert.

The ethics of taking advantage of children's comparative lack of knowledge, experience and critical thinking skills to inculcate religious dogma are already questionable. But much of CEF's activity is especially exploitative.

For example, their recent 'Hope for Ukraine' scheme cynically uses Russia's invasion of Ukraine as an opportunity to send "gospel packs" to Ukrainian children. These contain pamphlets telling children to ask Jesus to forgive their sins because: "King Jesus is in Heaven now but one day He will come back to our world. He will punish forever all those who have chosen to live their own way. He will welcome all His forgiven friends".

What effects does evangelism have on children? We've only recently begun to understand that in some cases, religious inculcation can be harmful. The term "religious trauma syndrome", coined a decade ago, is now an increasingly common description for a set of symptoms, including anxiety, depression and relationship issues, experienced "as a result of prolonged exposure to a toxic religious environment". And children, whose minds are still developing, are uniquely vulnerable to this condition.

Despite the ethical implications, child evangelism is far from unusual. Most branches of Christianity make a particular effort to preach to children. It's one of the main reasons why the Church of England, the Catholic Church and other major religious institutions are dedicated to maintaining a vice-like grip on a third of state schools, disproportionate influence over religious education (RE), and stubborn resistance to ending our archaic collective worship laws.

CEF is clear that it uses the collective worship laws and RE as a means to get to children at their schools, where they are a captive audience, and further their evangelising mission. And it is far from alone in this initiative.

There are now numerous charities whose main purpose is to send preachers into schools and proselytise to children. School teachers, grateful that someone else can take on collective worship and RE duties, frequently buy into the idea that these groups are merely promoting 'religious literacy' and are unaware of their real priorities. As CEF says: "Our ministry is not to entertain the children, nor even to educate them, but to evangelise them".

Before the pandemic and subsequent social distancing measures, issues relating to evangelism in schools were the most common types of casework the NSS dealt with.

One of the charities the NSS receives most complaints about is Scripture Union (SU). Their sessions have included an 'abstinence-only' approach to sex education. Another school evangelism charity the NSS has dealt with is Cross Teach, which according to parents told children that if they did not believe in God "they would not go to a good place when they died".

And new child evangelism charities continue to join the register. Last year the Programme For Applied Christian Education (PACE) re-registered as a Charitable Incorporated Organisation. One of its missions is "helping everyone in schools explore the Christian faith" through lessons, assemblies and lunchtime clubs. Its teaching materials include statements like "Abortion = Bad, Adoption = Good", marriage is "ideally" one man and one woman, and hell is where "God perfectly punishes all the sin of those who never wanted his forgiveness" .

And many more have registered which do not deliver school sessions but do run Sunday Schools and other out-of-school activities for children, or hold overseas evangelical work with a specific focus on children.

All this begs the question – why are these organisations registered charities at all?

Charities are supposed to provide a public benefit in exchange for the generous tax breaks, Gift Aid and other financial perks such status gives, in addition to public trust. But it's very difficult to see how charities set up with a specific purpose to evangelise, and ultimately convert, children fulfil that benefit.

I'm sure many child evangelists sincerely believe they are providing a public benefit, because they truly think they are saving children from hell. Indeed, this used to be a mainstream view – back in a time when most people believed in hell.

But today, most Brits don't have religious beliefs, let alone a belief in hell. Conversely, evidence indicates that inculcating children with fundamentalist religion risks a multitude of psychological harms. This should be enough to dislodge the notion that advancing religion through child evangelism is a public benefit.

But charity law hasn't caught up with the present. "The advancement of religion" is still a charitable purpose in law because there is still an underlying assumption that advancing religion, whatever form that may take, is inherently beneficial to society.

Our charity sector should not be used as a vehicle for furthering religious interests at the expense of children's mental health and freedom to explore religion or belief on their own terms. And neither should our schools be used as mission fields. We need to truly modernise our laws governing both charities and education if we want to prioritise the education and welfare of children above religious concerns.

Tackling child abuse in religious settings: What must happen next

As the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse draws to an end, Richard Scorer explains what the government needs to do to prevent abuse in religious settings and to ensure justice for survivors and victims.

On 20th October the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) will publish its final report, bringing IICSA to an end eight years after it was first established. Over that period IICSA has investigated a wide range of institutions in England and Wales, both religious and secular. Religious organisations examined include the Catholic Church, the Anglican Church, and (more superficially) various minority religions. The final report will focus on recommendations. What do we need from it?

In my view, four recommendations are particularly important to survivors of abuse in religious settings.

1. Mandatory reporting law

The most important – as I and so many others have said before – is mandatory reporting. A mandatory reporting law imposes a legal obligation on specified individuals ("mandated persons") to report known or suspected cases of child sexual abuse to specified state agencies. Most countries now have mandatory reporting in some form including 86% of European nations, so England and Wales are out of step with the rest of the world in not having it.

Many institutions suffer from reputational pressures leading to them covering up abuse, but as IICSA has confirmed, the pressures for reputational protection at the expense of children are particularly acute in religious settings, and it was because of church scandals that the Australian Royal Commission placed such emphasis on mandatory reporting.

In England and Wales it remains legal, in 2022, for a member of the clergy to know that a child has been raped, and not to report it. This is unacceptable and IICSA has unearthed more than enough evidence to justify changing the law.

However, IICSA needs to recommend real mandatory reporting, not a faux version of it. Reforms that fall short of real mandatory reporting are likely to be ineffective. Given the systematic cover up of abuse in the Catholic Church, it may be tempting for IICSA to recommend a criminal offence of concealment of abuse. But in practice, such an offence is likely to be very difficult to prosecute to the criminal standard. Ireland introduced a "Criminal Justice (Withholding of Information on Offences Against Children and Vulnerable Persons) Act" in 2012; there has not yet been a single prosecution under the Act. We need a legal regime which works, and which changes culture.

The pressure group Mandate Now have developed a well-designed mandatory reporting model. Their draft law has several key features:

- It requires the reporting of known or reasonably suspected child sexual abuse.

- It applies to "Regulated Activities", i.e. personnel responsible for the care of children within institutional settings, not to the population as a whole (laws which purport to do the latter are generally ineffective). Some religious activities involving children sit outside the current definition of Regulated Activity, but Mandate Now has designed a clause that includes them in its legislative proposal.

- The reporting requirement is backed up by the threat of criminal penalties for non-reporting. It cannot be stressed enough that the purpose of well-designed mandatory reporting is not to criminalise people, but to embed a culture of reporting and to protect good people who report concerns from detriment. This might include bullying or being put under pressure not to report, as graphically exposed in the IICSA report on the scandal at St Benedict's Ealing. To have teeth, mandatory reporting needs a proportionate criminal sanction. When the Irish government introduced a version of mandatory reporting in 2015, following the devastating report into recent cover ups of clerical sex abuse in the Catholic Diocese of Cloyne, it failed to include any sanction for non-reporting. The Irish government argued that that mandated persons who broke the law would suffer disciplinary sanctions from their professional body. But as the Cloyne report demonstrated, the Irish Catholic Church continued to conceal abuse after publicly committing to reporting it to statutory authorities in 1996, so it is unrealistic to imagine the church can be relied upon to apply meaningful internal sanctions.

- The reporting obligation needs to apply to not just to the operators of the setting but also to all other employed, contracted or voluntary staff for the time they are personally attending such children in the capacity for which they were employed. It's not just the leadership team at the top of the organisation; we know from IICSA just how often those in leadership positions in religious organisations choose not to see or hear what their subordinates are trying to tell them, so mandatory reporting has to give all those working with children in those settings the cover to report directly. This is important: leaving the reporting in the hands of religious leaders who have failed so egregiously to do it up to now would be a recipe for further concealment.

- Finally, there can be no religious exemption or when it comes to the confessional: I explain here why such exemptions are wrong. Even Cardinal Nichols in his evidence to IICSA appeared to accept the seal of the confessional is at odds with the legal principle that the interests of the child should be paramount.

2. Empowering agencies to respond to abuse

Mandatory reporting cannot be introduced in a vacuum. Agencies have to be resourced to respond to it. Alongside it we need an overhaul of the mechanisms for oversight of safeguarding in religious settings. As the IICSA counsel observed, currently these settings are less well-regulated than donkey sanctuaries.

The inadequacies of inspection systems operated by Ofsted and other oversight bodies such as the Charity Commission were very obvious from the hearings. Achieving effective regulation is a major challenge, particularly given the sheer number and variety of religious settings, which range from large settings such as cathedrals down to house churches involving just a few people. But we need to make a start.

And when it comes to investigating abuse in religious settings, a change in police attitudes is also necessary: there has sometimes been a reluctance to investigate abuse in minority religions for fear of stoking community tensions. This has to change if victims and survivors of abuse in religious settings are to have meaningful access to justice.

3. No more time limits for child abuse civil claims

We need to abolish the unfair and antiquated law on time limits for civil claims, which has often prevented legitimate compensation claims from going forward.

The law in England and Wales states that a civil claim for childhood sexual abuse should be brought within three years of the victim turning 18. This is a totally unrealistic expectation given that the average time delay between abuse and a survivor's disclosure is 22 years. Although the courts in England and Wales do have the power to set aside this three year time limit, it should not exist in the first place. Scotland has already (in 2017) abolished the three year time limit.

Some religious organisations, particularly the Catholic Church, have been particularly aggressive in relying on limitation defences. The three year time limit needs to be removed in England and Wales too.

4. Full compensation for survivors

Finally, we need proper redress for survivors. A civil claim is often a distressing and highly adversarial process. One reform idea is to work towards a single national redress scheme, funded by the organisations where children have suffered abuse. Personally I think this a recipe for many years of argument about who contributes what. In Ireland, the Catholic Church got away with contributing vastly less than it should have done, leaving the taxpayer to pick up much of the bill for clerical sex abuse, a totally perverse outcome.

A better approach may be to ensure that organisations where abuse has occurred themselves offer proper redress to help to compensate for the terrible harm caused by abuse. The Church of England, a very wealthy organisation, has been promising a national redress scheme for some time, but keeps delaying its introduction, leaving some survivors in a desperate position. I hope that IICSA will force the pace on this, so that compensation can become easier for survivors, whilst prohibiting any removal of the opportunity for a civil claim, should the survivor wish to proceed with one.

Of course, these are not the only changes we need to see. Lots of other issues have been highlighted by IICSA, for example the dangers of unregistered religious schools.

An issue which needs much more attention is the Church of England's unjustified exemptions from statutes governing other public sector bodies such as freedom of information laws. But for survivors and those who represent them, the changes highlighted above particularly important.

During the hearings, IICSA's chair, Professor Alexis Jay, has been tight lipped about what reforms she has in mind, and the various reports issued by IICSA so far have been similarly unrevealing. The under-resourcing of society's response to child abuse has been the 'elephant in the room' throughout IICSA, and many survivors fear that the 'dead hand of the Home Office' may deter the inquiry panel from recommending the necessary reforms; we shall see. Despite several years of hearings we have no real idea as to whether IICSA will embrace these reforms or not.

And of course even if it does, we face a political battle to ensure that the reforms are implemented by government, and not watered down or abandoned. However, when the final report comes out on 20 October, IICSA will be judged primarily on how it addresses these key issues.

Our head of state should not have constitutional ties with religion

As King Charles assumes the title of Defender of the Faith, Stephen Evans argues that the role of head of state in a modern democracy should have no constitutional ties to religion.

In his first address to the nation as monarch, King Charles said he would endeavour to serve all his subjects whatever their "background or beliefs" with loyalty, respect and love.

It would be easier to give credence to the sincerity of this statement if our head of state didn't also assume the dual role of head of the Church of England.

Upon the death of Queen Elizabeth, King Charles immediately became the Church's Supreme Governor and "Defender of the Faith". For the avoidance of doubt, that faith is the "one true protestant faith".

His coronation in Westminster Abbey next year will be a deeply religious affair. He will be anointed with holy oil, blessed, and consecrated by the archbishop of Canterbury. Holy Communion will be celebrated.

Ours is the only monarch left in Europe still crowned in a religious ceremony. All others have abandoned coronations or replaced them with simpler ceremonies to mark an accession.

A religious coronation is a peculiar way to inaugurate a head of state in one of the least religious countries on Earth. The UK's religious landscape has changed out of all recognition since the last coronation in 1953. We now have a non-religious majority and a significant proportion of citizens who follow non-Christian religions.

Many of them will feel alienated by a ceremony purporting to legitimise a new head of state where he pledges to protect the privileges and doctrine of a church they don't belong to. And let's not forget, the doctrine King Charles will swear an oath to preserve asserts that gay sex is a sin, and that same-sex marriage is illegitimate.

It is also a Church that represents just one UK country whose weekly attendance is only one per cent of the UK population.

We expect our monarchs to remain strictly neutral with respect to political matters. So why the double standard when it comes to religion?

Is it really appropriate for the UK prime minister to have a weekly meeting with the Supreme Governor of the Church of England to discuss government matters? With Anglicanism so deeply entrenched in our constitution it's hardly surprising that religious privilege runs through Britain like the letters in a stick of Blackpool rock.

King Charles has made clear his intention to be a defender of faith generally, not only the faith. This fits with the role the Church of England has assumed for itself as a means by which other denominations and faith communities can be elevated in public life.

It's not clear to what extent members of other faiths are content to ride on the coattails of the Anglican establishment. But clearly many faith leaders enjoy the enhanced status granted by the Church of England holding the door open for them. Humanists may on occasion be invited along, but ultimately, the favouritism shown to the Church of England, with 'crumbs from the table' for other religious groups, demeans minority faiths and almost entirely neglects and disenfranchises the nonreligious and religiously unconcerned majority.

Both the late Queen Elizabeth and King Charles have been advocates for religious freedom. They have nevertheless seemed unconcerned that the role of head of state in our democracy is reserved exclusively for practising Christians. The monarchy's religious role is underpinned by an assumption that all future monarchs will be believing Anglicans – indeed, the constitution prevents Catholics from becoming the monarch. How is this compatible with concepts of fairness or freedom of religion or belief?

The accession of a new King will inevitably raise questions about the relevance of monarchy in a modern democracy. After all, inherited power and privilege by virtue of birth is an affront to everything modern Britain claims to stand for.

Turning a blind eye to a morally unjustifiable institution at the heart of our constitution, which claims a 'divine right' to rule over the rest of us, can't be good for our national psyche. Nor can cleaving to our past in the absence of any confidence in our ability to carve out a democratic future.

It will therefore be interesting to see the extent to which apparent support for the monarchy has been tied up with an admiration and respect for Queen Elizabeth. But for as long as the monarchy remains, it is right and reasonable to initiate reforms to ensure our head of state has no constitutional entanglement with religion.

There is clearly a fondness both at home and overseas for our costumed British pageantry. As the Queen's state funeral demonstrated, it's something we do well. But concepts of nationhood and citizenship are too important to centre around an anachronism.

If we want those living within these isles, irrespective of creed, colour or belief, to buy into Britishness and feel part of a cohesive collective, our national identity must be meaningful and inclusive. It too often feels like a pretence, cherished by some, but alienating to others. Even our religious and monarchical national anthem, God Save the King, is exclusionary, lacking meaningfulness for nonbelievers and republicans.

A constitutional settlement based on Anglican supremacism is a non-starter for a country that aspires to be a beacon of freedom and equality. It's time we had a serious debate about the kind of country we want to be.

A version of this article was originally published by The Independent.

Iran protests are a reminder that the hijab is symbol of subjugation

In a country where removing the headscarf is a punishable crime, women burning their hijabs deserve our solidarity.

Something at once heartening and deeply depressing is happening in Iran.

Amid a rising death toll, brave Muslim women are taking to the streets, burning their hijabs, and claiming their freedom not to wear them.

The protests erupted following the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian Kurdish woman, shortly after being detained by the 'morality police' for allegedly not complying with the regime's strict hijab rules. Activists say Amini was beaten by police officers while in detention, causing her serious injuries that led to her death. Police deny the allegations.

Protests have since spread from the capital Tehran to at least 50 cities and towns nationwide.

Iranian authorities and a Kurdish rights group have reported rising death tolls. Amnesty International say security forces have used metal pellets, tear gas, water cannons, and beatings with batons to disperse protesters.

Ever since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, authorities in Iran have imposed a mandatory dress code requiring all women to wear a headscarf and loose-fitting clothing that disguises their figures in public. The law has been strictly enforced by Gasht-e Ershad agents, better known as the 'morality police', who have been have admonishing and terrorising women for decades.

Now the Islamic regime is rattled. To placate protesters, Iran's minister of culture, Mohammad Mehdi Esmaili, said on Wednesday the regime was already considering changing the morality police before Amini's death. "We recognise criticisms… and many of the existing problems will be addressed." The head of the morality police has reportedly been suspended from his post. But few will be reassured.

Meanwhile, the regime has placed restrictions on social media and there are signs that it may be poised to use even more force against protesters.

Despite often being touted as an expression of Muslim women's empowerment, the situation in Iran is a reminder that the hijab is symbol of subjugation. Iran's requirement that women – and only women – cover their head is rooted in the misogyny of the fundamentalist religion at the heart of the country's theocracy. It is misogyny that too many religious institutions, included some that are registered charities in the UK, are only too happy to promote in order to maintain the patriarchal status quo.

To wear a hijab or not should be a personal choice. For many Muslim women and girls around the world, it simply isn't. Choice can be restricted in many ways, through laws, coercion, or community pressure.

And in a country where removing the hijab is a punishable crime, the protestors deserve international support and solidarity. May their voices undermine theocracy in Iran and herald a new dawn for women's rights and freedoms.

Image from Isaac Nowroozi, via Twitter.

Talk of a public appetite for religion is wishful thinking

The established church's proclivity to insert itself into the secular realm should not go unchallenged, argues Stephen Evans.

Events around the Queen's death have led several commentators to become excited about what they see as enthusiasm for Christianity in Britain.

Under the headline "Britain is yearning for traditional Christianity", Telegraph columnist Madeline Grant remarked that "this traditional funeral – an unambiguous statement of Anglican faith – drew one of the biggest audiences in TV history." She opined that Queen Elizabeth's funeral "proved" the public doesn't want a dumbed down version of the Church.

Meanwhile, religion commentator Catherine Pepinster likened the queue to a "pilgrimage", remarking that people "crossing themselves, bowing and making other religious gestures before the coffin" (not that bowing before a coffin is a religious gesture) means "Britain is not as secular as we might assume".

In a Religion Media Centre briefing, the public's response was described as "religious". Professor Rev Ian Bradley, Emeritus Professor of Cultural and Spiritual History at the University of St Andrews, said "events of the last week have exposed and unleashed a latent spirituality".

All of this will be no doubt be utilised to promote more religion in public life.

But I'm not convinced people tuning in for the Queen's funeral reveals a hidden and untapped yearning for Christianity. It did attract a massive audience (at 29 million only slightly less that the Euro 2020 football finals). Given the national shut-down and the only other thing on television being The Emoji Movie, this isn't surprising.

As the Queen was a practising Christian and 'Defender of the Faith', her funeral was inevitably a religious event. But it was also perhaps the grandest state occasion in living memory. A national event to bid farewell to the longest-reigning and much-admired British monarch. My guess is people were watching for a variety of reasons. Many may have 'tuned out' of the religious bits.

It's also important to note that ritualism should not be mistaken for religiosity. It's clear that most people's tributes to the Queen, while full of symbolism and tradition, were secular in nature - noticeably so, in fact.

As Peter Stanford, a former editor of the Catholic Herald noted in The Guardian: "The need for ritual to mark a death has been with us since before religion came along. It is hard-wired into the human psyche to yearn for something more when a life comes to an end, whether for the person who has left us, or for ourselves. The genius of religions – consciously or not – has been to develop whole theologies and funeral rituals around that urge."

So, is there an appetite for more Christianity in public life, or there is a lot of wishful thinking going on? My money's on the latter.

The reality is attendance at Anglican services has been declining since the mid-19th century. The latest available Church of England data shows that average Sunday attendance is around 600,000 adults, or fewer than 1% of the population. A third of those attending church are aged 70 or over.

Figures from the 2018 British Social Attitudes survey showed that 52% of the UK public said they did not belong to any religion, while only 38% identified as Christian. We're likely to see the drift away from Christianity continue when the national census figures are published later this year.

The entanglement between religion and monarchy means the Queen's death has provided a significant national platform for the Church of England. But its message is unlikely to resonate.

Earlier this year, the Archbishop of Canterbury reaffirmed a 1998 declaration asserting that gay sex is a sin, and that same-sex marriage is illegitimate. Meanwhile, a soon to be concluded Independent Inquiry into Child Sex Abuse has found the Church of England has failed abuse survivors and victims by defending alleged perpetrators instead of protecting children and young people from sexual predators.

Is it any wonder that surveys show as few as one percent of 18- to 24-year-olds now identify as Anglican?

The Church's lavish spending on evangelism (£248 million was spent between 2017 and 2020 as part of the church's "renewal and reform" programme to attract new worshippers) is looking like money down the drain.

With pews emptying the Church is increasingly keen to insert itself into public life. Last week, the Anglican Dioceses of London and Southwark dispatched chaplains to 'the queue', to offer pastoral support, introduce themselves, have conversations, and, "only if requested, pray with people." Thousands of Great North Run participants were kept waiting at the start line while an Anglican priest read a prayer urging them to "run together… through Jesus Christ our Lord."

Schools are already a key part of its evangelism via faith schools and mandatory worship, but the CofE is now seeking to gain a foothold in further education colleges to try and "build a younger and more diverse church". The Church is also hoping, with support from religious MPs, to play a much greater role in delivering healthcare and other public services.

Most of the above is inappropriate. It's legitimised by the Church of England being the established church. But the concept of national church is divorced from reality and modernity. The Church of England likes to see itself as a church for all. But Britain is too diverse to sustain such a vision. Citizens and communities can coalesce around many things. But Christianity is not one of them.

For the most part, the British public has put up with the Church's encroachment. But the Church's ability to insert itself into the secular realm and impose itself upon a largely indifferent population should not go unchallenged. It should of course be free to compete in the marketplace of ideas, but on terms of equality, not privilege. Freedom of religion should always be balanced against freedom from religion. Secular spaces should be protected.

Image: The queue for Queen Elizabeth's lying-in-state. Frank Carman, CC BY 2.0

Blasphemy laws, not books, belong on the bonfire

During Banned Books Week, Helen Nicholls examines the impact of blasphemy laws on those who write about religion – both in the past and today.

In the Middle Ages, it was not only books that were burnt but also authors and publishers. Anyone connected with a heretical or blasphemous work could potentially be burned at the stake.

In 1524 William Tyndale was forced to flee Britain for the 'crime' of translating the Bible into English. He was captured in Belgium and was strangled and burnt at the stake in 1536. His work could not be suppressed and was a major influence on later authorised Bibles, including the King James Bible.

As Britain became more liberal, the penalties for blasphemy became less severe, although fines and prison sentences could still be ruinous for those targeted. The last person to be imprisoned for blasphemy in Britain was John William Gott in 1922. His health was so badly affected that he died later that year.

Blasphemy laws were repealed in England and Wales in 2008 and in Scotland in 2021. They remain in force in Northern Ireland. But the existence of blasphemy laws anywhere can have a devastating impact on freedom of expression globally.

In 1989 Ayatollah Khomeini, the supreme leader of Iran, issued a fatwa that invited Muslims worldwide to kill the author Salman Rushdie and anyone involved with his book The Satanic Verses. Rushdie went into hiding for many years. In 1991 Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses, was found murdered at his university. Others involved with the production and sale of the book faced violence. Rushdie himself was stabbed onstage at an event in New York in August but thankfully survived.

One consequence of the fatwa was that The Satanic Verses has been far more widely read than it otherwise would have been. However, the fatwa nevertheless had a chilling effect on free speech as few writers or publishers would be prepared to risk suffering the same fate as Igarashi or Rushdie.

This was demonstrated in 2008 when The Jewel of Medina, a historical novel about Aisha, the wife of the Islamic prophet Mohammed, was dropped by its publisher due to fears that the book would be considered inflammatory. Martin Rynja, founder of Gibson Square publishers, announced his intention to publish it but changed his mind after his home was firebombed. The book was never published in the UK although the American edition is available here.

In recent years, there have been further attacks on those perceived to have insulted Islam. The most notable is the attack on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015 following its publications of cartoons of Mohammed. In 2020, teacher Samuel Paty was murdered in France for showing his high school class a Charlie Hebdo cartoon of Mohammed during a discussion on free expression. The following year, a UK teacher was forced into hiding after doing the same thing.

In the UK, no-one fears being killed by the state for blasphemy, but many fear being murdered if they are accused of insulting Islam. This de facto blasphemy law is perhaps harder to counter than a judicial one as there is no due process or mechanism for repeal. However, we can start by challenging those who claim that violence is an acceptable response to a novel or cartoon and support those who find themselves targeted by violent extremists. Otherwise, we risk having a right to free speech that exists in law but not in fact.

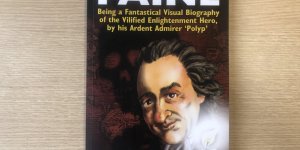

An exciting and unique introduction to the life of Thomas Paine

Paul 'Polyp' Fitzgerald's Paine: A fantastical visual biography is a new graphic novel on the life of Thomas Paine, a key figure in the history of secularism. Helen Nicholls explores how the book's unique approach helps keep Paine's story – and legacy – alive.

"He who dares not offend cannot be honest", wrote Thomas Paine in response to a critic. Paine's determination to speak his mind had serious consequences. In 1792, the British Attorney General prosecuted Paine for seditious libel for his book, The Rights of Man, which argued for a constitution based on democracy and human rights. Paine avoided imprisonment by escaping to France but his booksellers and publishers each received a sentence of three years' imprisonment. Paine was burned in effigy throughout England. He declared that the government had "honoured [him] with a thousand martyrdoms".

Paine's advocacy of freedom of expression and human rights is just as relevant today: religious fundamentalism continues to oppress and subjugate individuals, communities and societies around the world. Yet the life of Paine is not well known outside academic circles.

However, a new "visual biography" of Paine by cartoonist Paul Fitzgerald, also known as "Polyp", seeks to remedy this by telling his story in graphic novel format. Polyp said he produced Paine: A fantastical visual biography "as a way of paying homage to the world's least known revolutionary freethinking hero, and hopefully rescuing him from oblivion".

While Paine was a deist, believing in non-interventionist creator, his legacy has been largely preserved by atheists and secularists. In keeping with this tradition, the National Secular Society was a contributor to Polyp's crowdfunder to produce Paine's biography.

The book is narrated entirely through extracts from historical sources. Many are quotes from Paine's own writings. The rest come from his contemporaries, both supporters and detractors. It is beautifully illustrated and gives a vivid portrayal of its settings.

Most panels faithfully depict Paine's era - but with an irreverent streak. Paine is portrayed in one panel as Mr Spock, while another places him on the cover of Charlie Hebdo, reminding the reader that the struggle for the freedom to criticise religion persists to the present.

Paine would not have called himself a secularist as the word did not exist in his lifetime. However, he espoused the principles that form the basis of secularist thought. His greatest skill was his ability to communicate his ideas to the general public. But he was a victim of his own success as the popularity of his ideas and the threat they posed to the political and religious establishment meant that he was widely hated in his lifetime. The graphic novel brings this struggle to life, showing Paine as a brilliant but obstinate man who suffered personally for his work.

The book ends on an optimistic note, with quotations from admirers ranging from Abraham Lincoln to Christopher Hitchens. Polyp also includes quotations from G.J. Holyoake, who coined the term "secularist", and former National Secular Society President G.W. Foote, who said of Paine: "The keenness of his intellect was matched by the brilliancy of his imagination. His name stands for mental freedom and moral courage".

Paine: A fantastical visual biography is an excellent introduction to Paine for anyone interested in the history of secularist thought in an entertaining and accessible format.

Paine: A fantastical visual biography is available on Polyp's website here.

Watch NSS council member and historian Bob Forder tell Paine's story:

The Ayatollah will not have the last word

Salman Rushdie's battle is the battle of all of us who stand on the right side of history, says Pragna Patel.

The television images of the ferocious knife attack on Salman Rushdie on Friday 12 August 2022 have left me - like many others - in a state of shock and horror. It seems incomprehensible that decades after the fatwa pronounced by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, Rushdie has been attacked by a 24-year-old man who wasn't even born when The Satanic Verses was published. Fortunately, it appears that Rushdie will survive and, with him, our hope for humanity's freedom and progress.

For me, this attack on Rushdie is a particularly sobering moment. Like the fatwa in the first instance, it marks another milestone in my political journey as a black feminist, a journey divided into two distinct periods: Pre-Rushdie and post-Rushdie.

The pre-Rushdie period of the 70s and 80s represented a time when many minorities in the UK mobilised around the secular term 'black' on the basis of our common histories of colonialism and racism. Inspired by the American civil rights movement and other progressive global movements for independence and social justice, we sought to challenge prejudice, bigotry and discrimination, and to forge a form of anti-racist politics that was capable of bridging the gap between anti-racism, feminism and socialism. We sought to build solidarity based on challenging all kinds of oppression anywhere, everywhere and all at once.

The post-Rushdie period followed the Ayatollah's fatwa against Rushdie amidst the rise and consolidation of regressive and even violent forms of identity politics, especially but not solely in minority communities. It is a communal politics marked by a rejection of the secular and universal principles of human rights and democratic freedoms, including the right to autonomy and freedom of conscience and expression. Disturbingly, it is embraced not only by the Right, but also by many on the Left: those who have often allied with the most reactionary forces in the belief that fighting racism and imperialism is the only game in town.

Women Against Fundamentalism (WAF) was formed in the wake of the fatwa against Rushdie. By publicly defending Rushdie we sought to disrupt a developing public consensus that this was merely a battle between freedom of speech and freedom of religion. We organised a counter protest – attended by black and white feminist women in Parliament Square – against thousands of enraged and mostly young male Muslim demonstrators calling for Rushdie's death.

In fear of our own lives, we held up placards and chanted slogans and songs that conveyed our political perspective, because this was a battle between theocrats and democrats in which we as feminists had a key stake. Feminism, we said, is in the business of dissenting from the patriarchal order which, in the name of religion and culture, justifies violence against women and restricts our right to our own bodies and minds. We argued that fundamentalist forces in every religion, if uncontested, will go on the offensive, and women will be amongst the first casualties of their bid for absolute power.

Ironically, that moment also encapsulated our simultaneous struggle against racism when we found ourselves challenging a white racist and fascist mob who, having arrived at the scene, saw as us the easier targets upon which to focus their own politics of hatred and exclusion.

Three decades later, we are living with the legacy of failure: the failure of democratic states and the Left alike to challenge religious fundamentalism and to safeguard the principles of democracy and citizenship. The lurch towards political and religious authoritarianism has brought with it the normalisation, and even celebration, of a culture of intolerance and censorship - one aimed at silencing any dissent, from women as well as religious and sexual minorities, writers, journalists, artists and all who refuse to submit.

In the wake of the assault on Rushdie, we understand now, as we understood in 1989, that Rushdie's battle is every woman's battle. It is the battle of all of us who stand on the right side of history. The Ayatollah will not have the last word.

Read the Feminist Dissent statement here, echoing the 1989 WAF statement.

Pragna Patel will talk more on the issue of feminism and secularism, including Southall Black Sisters' support of Salman Rushdie, at the 2022 Bradlaugh Lecture at Manchester Art Gallery on October 1st. Find out more and book your place.

The silencing of Salman Rushdie must not succeed

The best way to show solidarity with Salman Rushdie is by making sure his voice continues to be heard, says Stephen Evans.

The attack on Salman Rushdie on Friday was another in a long line of attacks on the very bedrock of liberal democracy: free expression.

It was a shocking attack. One of Britain's most successful authors, violently and repeatedly stabbed as he was taking the stage at a bastion of free speech – the Chautauqua Institution, which describes itself as "a community of artists, educators, thinkers, faith leaders and friends dedicated to exploring the best in humanity".

Ever since the publication of The Satanic Verses in September 1988, Salman Rushdie has come to symbolise the battle between two conflicting ideas: freedom of expression and a medieval concept of blasphemy.

Rushdie's novel, inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, instantly enraged reactionary Muslims who found the book offensive and accused Rushdie of blasphemy. India banned the book just nine days after it was published in the UK. Pakistan and Saudi Arabia swiftly followed suit. In 1989 the Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran issued a 'fatwa' calling on "all valiant Muslims" to kill Rushdie "without delay, so that no one will dare insult the sacred beliefs of Muslims henceforth." The British government placed Rushdie under police protection, and he was forced into hiding.

The events marked a low point for community relations in Britain. British Muslims were poorly served by their self-appointed community leaders. Iqbal Sacranie, a former Secretary General of the Muslim Council of Britain, remarked: "Death, perhaps, is a bit too easy for him, his mind must be tormented for the rest of his life unless he asks for forgiveness to Almighty Allah."

Rushdie resurfaced in the late 1990s after almost ten years of isolation and cautiously resumed more public appearances. Since then, he has lived openly and courageously, refusing to submit. "How to defeat terrorism? Don't be terrorised. Don't let fear rule your life. Even if you are scared," he reasoned.

But the 'Rushdie affair' gave rise to an insidious new stealth blasphemy code, with transgressions punished not by law, but by death, or at least the threat of it. As Rushdie himself identified: "'Respect for religion' has become a code phrase meaning 'fear of religion'. Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect."

But a string of Islamist atrocities has scared many into submission. Images of Muhammad are routinely censored. Criticism of Islamic practices is branded 'Islamophobic', and anything deemed offensive by fundamentalists is quickly shut down. A climate of self-censorship has emerged.

But Rushdie recognises that we cannot, as individuals or a society, be cowed by violent extremism or afford to place religion off limits for critical examination, literature, art or satire.

Pandering to fundamentalism is not a road to an open, tolerant or peaceful society. The Islamist demands will never be satiated. As the late Christopher Hitchens, a close friend of Rushdie, said: "We cannot possibly adjust enough to please the fanatics, and it is degrading to make the attempt."

We can't match their fanaticism, but we must match their resolve. Citizens of all faiths and beliefs need to stand side by side and demonstrate that we hold as firmly to our core values and freedoms as they hold to their warped extremist ideologies.

And political leaders must show leadership. That means no more half-hearted commitments to free speech. No more panicked pandering to offence takers. And no more victim blaming. Let's never lose sight of the fact that the responsibility for violence lies with those who perpetrate it.

Salman Rushdie once said that the writer's great weapon is the truth and integrity of their voice. The best way to show solidarity with him is by never allowing that voice to be silenced.

The 2015 General Election

GP who leads proscribed Islamist group suspended by NHS

NSS urges General Medical Council to consider whether Dr Wahid Shaida is fit to practice.

Michaela shows the need to end collective worship laws

The Michaela case demonstrates why we need a change in law to enable schools to promote a secular, inclusive ethos, says Megan Manson.

Peer calls for more secular democracy in RE debate

Lord Warner challenges prayers in parliament and schools, bishops' bench, and faith schools.

Hindu group threatens secularists with police over “offensive” talk

Hindu charity told Leicester Secular Society it would report talk on caste to local Hindu community and police.

Lives “endangered” at school which restricted prayer rituals

NSS calls for government action after school subjected to death threats and bomb scares.

NSS highlights religious barriers to inclusive education in NI

NSS response to inquiry calls for more integrated schools and more secular education system in Northern Ireland.

Ritual slaughter: is the government about to renege on its commitment to consult?

Stephen Evans criticises the government's U-turn on animal welfare and says food labelling policy should serve consumers rather than religious interests.

Labour announces plan for register of children not in school

Proposal to record children not attending school would help tackle unregistered faith schools, NSS says.

Faith schools “most socially selective”, report finds

Faith schools admit disproportionately fewer pupils on free school meals, says Sutton Trust.

NSS to hold event on tackling abuse in religious communities

Safeguarding experts in panel discussion in Manchester this March.