Talk of a public appetite for religion is wishful thinking

Posted: Thu, 22nd Sep 2022 by Stephen Evans

The established church's proclivity to insert itself into the secular realm should not go unchallenged, argues Stephen Evans.

Events around the Queen's death have led several commentators to become excited about what they see as enthusiasm for Christianity in Britain.

Under the headline "Britain is yearning for traditional Christianity", Telegraph columnist Madeline Grant remarked that "this traditional funeral – an unambiguous statement of Anglican faith – drew one of the biggest audiences in TV history." She opined that Queen Elizabeth's funeral "proved" the public doesn't want a dumbed down version of the Church.

Meanwhile, religion commentator Catherine Pepinster likened the queue to a "pilgrimage", remarking that people "crossing themselves, bowing and making other religious gestures before the coffin" (not that bowing before a coffin is a religious gesture) means "Britain is not as secular as we might assume".

In a Religion Media Centre briefing, the public's response was described as "religious". Professor Rev Ian Bradley, Emeritus Professor of Cultural and Spiritual History at the University of St Andrews, said "events of the last week have exposed and unleashed a latent spirituality".

All of this will be no doubt be utilised to promote more religion in public life.

But I'm not convinced people tuning in for the Queen's funeral reveals a hidden and untapped yearning for Christianity. It did attract a massive audience (at 29 million only slightly less that the Euro 2020 football finals). Given the national shut-down and the only other thing on television being The Emoji Movie, this isn't surprising.

As the Queen was a practising Christian and 'Defender of the Faith', her funeral was inevitably a religious event. But it was also perhaps the grandest state occasion in living memory. A national event to bid farewell to the longest-reigning and much-admired British monarch. My guess is people were watching for a variety of reasons. Many may have 'tuned out' of the religious bits.

It's also important to note that ritualism should not be mistaken for religiosity. It's clear that most people's tributes to the Queen, while full of symbolism and tradition, were secular in nature - noticeably so, in fact.

As Peter Stanford, a former editor of the Catholic Herald noted in The Guardian: "The need for ritual to mark a death has been with us since before religion came along. It is hard-wired into the human psyche to yearn for something more when a life comes to an end, whether for the person who has left us, or for ourselves. The genius of religions – consciously or not – has been to develop whole theologies and funeral rituals around that urge."

So, is there an appetite for more Christianity in public life, or there is a lot of wishful thinking going on? My money's on the latter.

The reality is attendance at Anglican services has been declining since the mid-19th century. The latest available Church of England data shows that average Sunday attendance is around 600,000 adults, or fewer than 1% of the population. A third of those attending church are aged 70 or over.

Figures from the 2018 British Social Attitudes survey showed that 52% of the UK public said they did not belong to any religion, while only 38% identified as Christian. We're likely to see the drift away from Christianity continue when the national census figures are published later this year.

The entanglement between religion and monarchy means the Queen's death has provided a significant national platform for the Church of England. But its message is unlikely to resonate.

Earlier this year, the Archbishop of Canterbury reaffirmed a 1998 declaration asserting that gay sex is a sin, and that same-sex marriage is illegitimate. Meanwhile, a soon to be concluded Independent Inquiry into Child Sex Abuse has found the Church of England has failed abuse survivors and victims by defending alleged perpetrators instead of protecting children and young people from sexual predators.

Is it any wonder that surveys show as few as one percent of 18- to 24-year-olds now identify as Anglican?

The Church's lavish spending on evangelism (£248 million was spent between 2017 and 2020 as part of the church's "renewal and reform" programme to attract new worshippers) is looking like money down the drain.

With pews emptying the Church is increasingly keen to insert itself into public life. Last week, the Anglican Dioceses of London and Southwark dispatched chaplains to 'the queue', to offer pastoral support, introduce themselves, have conversations, and, "only if requested, pray with people." Thousands of Great North Run participants were kept waiting at the start line while an Anglican priest read a prayer urging them to "run together… through Jesus Christ our Lord."

Schools are already a key part of its evangelism via faith schools and mandatory worship, but the CofE is now seeking to gain a foothold in further education colleges to try and "build a younger and more diverse church". The Church is also hoping, with support from religious MPs, to play a much greater role in delivering healthcare and other public services.

Most of the above is inappropriate. It's legitimised by the Church of England being the established church. But the concept of national church is divorced from reality and modernity. The Church of England likes to see itself as a church for all. But Britain is too diverse to sustain such a vision. Citizens and communities can coalesce around many things. But Christianity is not one of them.

For the most part, the British public has put up with the Church's encroachment. But the Church's ability to insert itself into the secular realm and impose itself upon a largely indifferent population should not go unchallenged. It should of course be free to compete in the marketplace of ideas, but on terms of equality, not privilege. Freedom of religion should always be balanced against freedom from religion. Secular spaces should be protected.

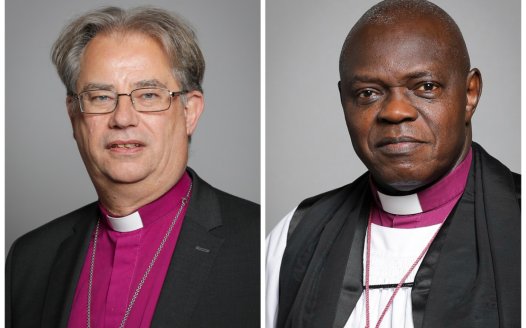

Image: The queue for Queen Elizabeth's lying-in-state. Frank Carman, CC BY 2.0

What the NSS stands for

The Secular Charter outlines 10 principles that guide us as we campaign for a secular democracy which safeguards all citizens' rights to freedom of and from religion.