Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change

The time has come to rethink religion's public role in order to ensure equality and fairness for believers and non-believers alike, says a major new report launched by the National Secular Society.

The report says that Britain's "drift away from Christianity" coupled with the rise in minority religions and increasing non-religiosity demands a "long term, sustainable settlement on the relationship between religion and the state".

Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change has been sent to all MPs as part of a major drive by the Society to encourage policymakers and citizens of all faiths and none to find common cause in promoting principles of secularism.

It calls for Britain to evolve into a secular democracy with a clear separation between religion and state and criticises the prevailing multi-faithist approach as being "at odds with the increasing religious indifference" in Britain.

Terry Sanderson, National Secular Society president, said: "Vast swathes of the population are simply not interested in religion, it doesn't play a part in their lives, but the state refuses to recognise this.

"Britain is now one of the most religiously diverse and, at the same time, non-religious nations in the world. Rather than burying its head in the sand, the state needs to respond to these fundamental cultural changes. Our report sets out constructive and specific proposals to fundamentally reform the role of religion in public life to ensure that every citizen can be treated fairly and valued equally, irrespective of their religious outlook."

Read the report:

Rethinking religion and belief in public life: a manifesto for change

Add your endorsement to the manifesto for change

Add your endorsementComplete list of recommendations

Our changing society – Multiculturalism, secularism and group identity

1. The Government should continue to move away from multiculturalism and instead emphasise individual rights and social cohesion. A multi-faith approach should be avoided.

2. The UK is a secularised society which upholds freedom of and from religion. We urge politicians to consider this, and refrain from using "Christian country" rhetoric.

The role of religion in schools

Faith schools

3. There should be a moratorium on the opening of any new publicly funded faith schools.

4. Government policy should ultimately move towards a truly inclusive secular education system in which religious organisations play no formal role in the state education system.

5. Religion should be approached in schools like politics: with neutrality, in a way that informs impartially and does not teach views.

6. Ultimately, no publicly funded school should be statutorily permitted, as they currently are, to promote a particular religious position or seek to inculcate pupils into a particular faith.

7. In the meantime, pupils should have a statutory entitlement to education in a non-religiously affiliated school.

8. No publicly funded school should be permitted to prioritise pupils in admissions on the basis of baptism, religious affiliation or the religious activities of a child's parent(s).

9. Schools should not be able to discriminate against staff on the basis of religion or belief, sexual orientation or any other protected characteristics.

Religious education

10. Faith schools should lose their ability to teach about religion from their own exclusive viewpoint and the law should be amended to reflect this.

11. The Government should undertake a review of Religious Education with a view to reforming the way religion and belief is taught in all schools.

12. The teaching of religion should not be prioritised over the teaching of non-religious worldviews, and secular philosophical approaches.

13. The Government should consider making religion and belief education a constituent part of another area of the curriculum or consider a new national subject for all pupils that ensures all pupils study of a broad range of religious and non-religious worldviews, possibly including basic philosophy.

14. The way in which the RE curriculum is constructed by Standing Advisory Councils on Religious Education (SACREs) is unique, and seriously outdated. The construction and content of any subject covering religion or belief should be determined by the same process as other subjects after consultation with teachers, subject communities, academics, employers, higher education institutions and other interested parties (who should have no undue influence or veto).

Sex and relationships education

15. All children and young people, including pupils at faith schools, should have a statutory entitlement to impartial and age-appropriate sex and relationships education, from which they cannot be withdrawn.

Collective worship

16. The legal requirement on schools to provide Collective Worship should be abolished.

17. The Equality Act exception related to school worship should be repealed. Schools should be under a duty to ensure that all aspects of the school day are inclusive.

18. Both the law and guidance should be clear that under no circumstances should pupils be compelled to worship and children's right to religious freedom should be fully respected by all schools.

19. Where schools do hold acts of worship pupils should themselves be free to choose not to take part.

20. If there are concerns that the abolition of the duty to provide collective worship would signal the end of assemblies, the Government may wish to consider replacing the requirement to provide worship with a requirement to hold inclusive assemblies that further pupils' 'spiritual, moral, social and cultural education'.

Independent schooling

21. All schools should be registered with the Department for Education and as a condition of registration must meet standards set out in regulations.

22. Government must ensure that councils are identifying suspected illegal, unregistered religious schools so that Ofsted can inspect them. The state must have an accurate register of where every child is being educated.

Freedom of expression - Freedom of expression, blasphemy and the media

23. Any judicial or administrative attempt to further restrict free expression on the grounds of 'combatting extremism' should be resisted. Threatening behaviour and incitement to violence is already prohibited by law. Further measures would be an illiberal restriction of others' right to freedom of expression. They are also likely to be counterproductive by insulating extremist views from the most effective deterrents: counterargument and criticism.

24. Proscriptions of "blasphemy" must not be introduced by stealth, legislation, fear or on the spurious grounds of 'offence'. There can be no right to be protected from offence in an open and free secular society.

25. The fundamental value of free speech should be instilled throughout the education system and in all schools.

26. Universities and other further education bodies should be reminded of their statutory obligations to protect freedom of expression under the Education (No 2) Act 1986.

Religion and the law

Civil rights, 'conscience clauses' and religious freedom

27. We are opposed in principle to the creation of a 'conscience clause' which would permit discrimination against (primarily) LGBT people. This is of particular concern in Northern Ireland.

28. Religious freedom must not be taken to mean or include a right to discriminate. Businesses providing goods and services, regardless of owners' religious views, must obey the law.

29. Equality legislation must not be rolled back in order to appease a minority of religious believers whose views are out-of-touch with the majority of the general public and their co-religionists.

30. The UK Government should impose changes on the rest of the UK in order to comply with Human Rights obligations. Every endeavour should be made by to extend same sex marriage and abortion access to Northern Ireland.

Conscience 'opt-outs' in healthcare

31. Efforts to unreasonably extend the legal concept of 'reasonable accommodation' and conscience to give greater protection in healthcare to those expressing a (normally religious) objection should be resisted.

32. Conscience opt-outs should not be granted where their operation impinges adversely on the rights of others.

33. Pharmacists' codes should not permit conscience opts out for pharmacists that result in denial of service, as this may cause harm. NHS contracts should reflect this.

34. Consideration should be given to legislative changes to enforce the changes to pharmacists codes recommended above.

The use of tribunals by religious minorities

35. The legal system must not be undermined. Action must be taken to ensure that none of the councils currently in operation misrepresent themselves as sources of legal authority.

36. Work should be undertaken by local authorities to identify sharia councils, and official figures should be made available to measure the number of sharia councils in the UK to help understand the extent of their influence.

37. There needs to be a continuing review by the Government of the extent to which religious 'law', including religious marriage without civil marriage, is undermining human rights and/or becoming de facto law. The Government must be proactive in proposing solutions to ensure all citizens are able to access their legal rights.

38. All schools should promote understanding of citizenship and legal rights under UK law so that people – particularly Muslim women and girls – are aware of and able to access their legal rights and do not regard religious 'courts' as sources of genuine legal authority.

Religious exemptions from animal welfare laws

39. Laws intended to minimise animal suffering should not be the subject of religious exemptions. Non-stun slaughter should be prohibited and existing welfare at slaughter legislation should apply without exception.

40. For as long as non-stun slaughter is permitted, all meat and meat products derived from animals killed under the religious exemption should be obliged to show the method of slaughter.

41. In public institutions it should be unlawful not to provide a stunned alternative to non-stun meat produce.

Religion and public services

Social action by religious organisations

42. The Equality Act should be amended to suspend the exemptions for religious groups when they are working under public contract on behalf of the state.

43. Legislation should be introduced so that contractors delivering general public services on behalf of a public authority are defined as public authorities explicitly for those activities, making them subject to the Human Rights Act legislation.

44. It should be mandatory for all contracts with religious providers of publicly-funded services to have unambiguous equality, non-discrimination and non-proselytising clauses in them.

45. Public records of contracts with religious groups should be maintained and appropriate measures for monitoring their compliance with equality and human rights legislation should be put in place.

46. There should be an enforcement mechanism for the above, which would for example receive and adjudicate on complaints without complainants having to take legal action.

Hospital chaplaincy

47. Religious care should not be funded through NHS budgets.

48. No NHS post should be conditional on the patronage of religious authorities, nor subject directly or indirectly to discriminatory provisions, for example on sexual orientation or marital status.

49. Alternative funding, such as via a charitable trust, could be explored if religions wish to retain their representation in hospitals.

50. Hospitals wishing to employ staff to provide pastoral, emotional and spiritual care for patients, families and staff should do so within a secular context.

Institutions and public ceremonies

Disestablishment

51. The Church of England should be disestablished

52. The Bishops' Bench should be removed from the House of Lords. Any future Second Chamber should have no representation for religion whether ex-officio or appointed, whether of Christian denominations or any other faith. This does not amount to a ban on clerics; they would eligible for selection on the same basis as others.

Remembrance

53. The Remembrance Day commemoration ceremony at the Cenotaph should become secular in character. Ceremonies should be led by national or civic leaders and there should be a period of silence for participants to remember the fallen in their own way, be that religious or not.

Monarchy and religion

54. The ceremony to mark the accession of a new head of state should take place in the seat of representative secular democracy, such as in Westminster Hall and should not be religious.

55. The monarch should no longer be required to be in communion with the Church of England nor ex officio be Supreme Governor of the Church of England, and the title "Defender of the Faith" should not be retained.

Parliamentary prayers

56. We believe Parliament should reflect the country as it is today and remove acts of worship from the formal business of the House.

Local democracy and religious observance

57. Acts of religious worship should play no part in the formal business of parliamentary or local authority meetings.

Public broadcasting, the BBC and religion

58. The BBC should rename Thought for the Day 'Religious thought for the day' and move it away from Radio 4's flagship news programme and into a more suitable timeslot reflecting its niche status. Alternatively it could reform it and open it up to non-religious contributors.

59. The extent and nature of religious programming should reflect the religion and belief demographics of the UK.

Add your endorsement to the manifesto for change

Add your endorsementThe 2017 General Election

The Church of England is legitimising spiritual abuse

The Exorcist director William Friedkin died at the age of 87 this week. His seminal film immortalised the concept of exorcism in our popular culture. But you may be surprised to learn the practice is alive and well in our established church.

The Church of England – the church which our head of state swears to maintain and which has formal representation in parliament – practises a "deliverance ministry" to this day. As of 2011, the Church of England had 44 exorcists, one per diocese, each appointed by the archbishop of Canterbury.

Indeed, the late Anglican exorcist Ken Gardiner said: "I have seen exorcisms succeed. People came to me in a state and, in the name of Jesus, I've commanded whatever was there to leave."

The Church's 2023 guidance allows parents to consent to "formal rites of deliverance" for their children, "including those involving touch". The "laying on of hands" may be deemed necessary to cast out "demons", it says.

Traumatising a child by telling them they are possessed with a demon, and that a priest needs to touch them to cast the demon out, is surely inherently abusive.

On top of this, the guidance asserts that, in the "majority of cases" of 16-17 year olds, the consent of parents does not need to be obtained. Medical advice must be sought but there is no explicit requirement to follow it. Perversely, there is only one third party whose permission is required: the local bishop.

In recent months, the Church has been publicly shamed by its abysmal record on child safeguarding: the ever-mounting allegations of sexual abuse at Soul Survivor church, the suspension of the former archbishop of York, the decision to sack its own Independent Safeguarding Board – to name but a few. One might expect they would know better by now.

Exorcism is also linked to the harmful and homophobic practice of so-called 'gay conversion therapy'. Just last year, Matthew Draper alleged he had been subjected to exorcism by a church in Sheffield in order to rid him of "the demons of homosexuality". The claims are now being investigated by the Diocese of Sheffield.

For the avoidance of doubt, Professor Sir Robin Murray of Kings College's Institute of Psychiatry has said he knows of no "scientific evidence that exorcism works".

The probable harms of Anglican exorcism are not limited to its own congregations. The Church's "deliverance ministry" legitimises more extreme forms of spiritual abuse by other faith groups.

Earlier this year, a newly registered religious charity in Belfast posted a Facebook picture laying out the "five kinds of witches". The post draws on a sermon given by Nigerian pastor Daniel Kolawole Olukoya. In an unhinged screed, Olukoya pontificates on "eaters of flesh and blood" and "the register of darkness" as parishioners nod approvingly. He enjoins his rapt followers to receive "deliverance" from demonic witches and wizards.

It would be easy to dismiss these beliefs as eccentric but they are, in fact, treated with deadly seriousness by some adherents here in the UK.

In 2000, Victoria Climbie was tortured to death after a Christian preacher convinced her family she was possessed by "evil spirits". The pathologist who examined her body said it was the worst case of abuse he had ever seen.

In 2015, Kristy Bramu was accused by his sister and her boyfriend of 'kindoki' - a Congolese form of witchcraft. He drowned in a "ritual cleansing" bath after being subjected to "sadistic" and "prolonged" torture.

In 2021, as part of an Islamic ruqya exorcism, anaesthetist Hossam Metwally put his partner Kelly Wilson into a coma and nearly induced cardiac arrest.

To our knowledge, Anglican exorcisms have not, in recent years, had fatal consequences. But they are inspired by the same sinister belief: that people can be by possessed by demonic forces and these forces can be overcome through religious intervention. The deliverance ministry of the established church, an arm of the British state, gives succour to the most dangerous forms of spiritual abuse.

Today, August 10, is the World Day against Witch Hunts – a day for standing up against the abuse and killing of people believed to be witches or 'possessed' by evil spirits. What better occasion for us to challenge the Church's perpetuation of spiritual abuse? Exorcism should be the preserve of fiction and future Friedkins, not the established church.

Image: Francisco Goya, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sexist state church should be disestablished

Imagine if a colleague of yours, due to his deeply held religious beliefs, refused to follow his manager's instructions because that manager is a woman. What would happen?

In almost all cases this would be unacceptable; places of work which tolerated it would probably find themselves on the wrong side of the law. Although both sex and religion or belief are protected characteristics under the Equality Act 2010, the law is clear that individuals cannot discriminate against their colleagues just because their religion says they should.

But there still exist niches where such obvious sexism is permitted – and one of those is the established church.

It is quite incredible that in the 21st century, 500 Church of England churches ban female priests. This is thanks partly to religious exemptions in the Equality Act, and partly to the 2014 House of Bishops' Declaration on the Ministry of Bishops and Priests issued when the Church finally decided to let women be bishops. The declaration includes the principle that the Church "remains committed to enabling" those who are "unable to receive the ministry of women bishops or priests" to "flourish".

In other words, men who don't want to suffer the indignity of accepting a woman's authority don't have to and will be continued to be welcomed by the Church with open arms.

Increasing numbers of CofE members find the Church's stance on female clergy abhorrent. The church of St Fimbarrus in the Cornish town of Fowey has recently u-turned on its prohibition of female vicars following a backlash from parishioners. Ironically, Fowey was once home to The Vicar of Dibley star Dawn French.

Growing numbers of parliamentarians are also challenging the Church's sexism. Last month Labour MP Diana Johnson challenged the Church's representative in the House of Commons, Andrew Selous, on this issue.

Selous' response? "The Church of England is fully committed to all orders of ministry being open equally to all without reference to gender. The Church is also committed to ensuring that those who cannot in good conscience receive the ministry of women priests or bishops are able to flourish".

Two mutually exclusive commitments, if ever there were. The Church will not be equally open to clergy of both sexes as long as it allows parishes to reject one of those sexes.

Some may argue that, unlike the Church's homophobic approach to gay marriage, this is a strictly internal affair which only affects female CofE clergy, not the wider public. But the established Church's commitment to helping misogynists within their ranks "flourish" has broader implications. It tacitly implies that there's something so subversive about women with authority that it's reasonable for men to reject them.

While women's rights in the UK have inarguably progressed, women are still underrepresented in positions of power and overrepresented as victims of domestic violence. The UK's gender pay gap stands at nearly 15%. A meagre nine percent of FTSE 100 companies and just under five percent of FTSE 250 companies had female CEOs in 2022. Only 35% of members of the House of Commons and 29% of the Lords are female. According to Refuge, one in four women in England and Wales will experience domestic abuse in her lifetime, two women a week are killed by a current or former partner, and domestic abuse drives three women a week to suicide. Ninety-three percent of defendants in domestic abuse cases are male while 84% of victims are female.

Religious promotion of female subordination upholds and feeds narratives fuelling discrimination and violence against women. Religiously sanctioned notions that women exist to serve men translate into decision making which limits women's opportunities, and into relationships which are coercive, controlling and abusive.

With church attendance rapidly dwindling, supporters of establishment are running out of justifications for the extraordinary privileges granted to the CofE. One often repeated justification is that the Church offers moral leadership with some sort of 'ethical insight' denied to the secular arms of the state.

But a church which prioritises keeping conservative male clergy appeased to the detriment of women who just want equal treatment doesn't seem particularly moral. Rather, it seems to be putting its own interests above those of the nation it claims to serve.

Just as the Church cannot credibly claim commitment to equality while allowing parishes to discriminate against female clergy, it cannot serve the needs of the nation while clinging to outdated dogma which holds back women's rights.

Parliamentarians know this, and they're weaponising the Church's established status against the Church itself. On the issue of female clergy, father of the house Peter Bottomly MP delivered an ultimatum: "The Church Commissioners should understand that either the Church of England gets rid of what ought to have been temporary exemptions from the Equality Act 2010 or Parliament will do that for it".

Perhaps parliamentarians ought to go one further and begin the disestablishment process themselves. After all, do we really want a religion with such an appalling record of homophobia and child abuse, as well as misogyny, as part of the architecture of our constitution?

The dignified and principled thing would be for the Church to jump before it is pushed: it should initiate disestablishment. That would give it the theological independence it craves while clearing our 21st democracy of the aberration of a state religion.

Now that would be serving the needs of the nation.

Image: gazlast92, Shutterstock

From Barbie to blasphemy: how religion muzzles free speech

This week, religious groups have found ways to be offended by both of the summer's biggest blockbusters. In Pakistan the Punjab censor board, widely believed to be in thrall to religious fanatics, has delayed the release of Barbie over "objectional content".

And in India, Hindu nationalists have called for a boycott of Oppenheimer, which features a reading from the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita during a sex scene. Cillian Murphy and Florence Pugh's lovemaking has been branded "a direct assault on religious beliefs" and a "conspiracy by anti-Hindu forces".

Petty grievances like these may appear inconsequential but they are the thin end of the wedge: they lay the turf for the growing global backlash against so-called blasphemy.

Earlier this month, the UN Human Rights Council passed a resolution banning the burning of religious texts. The resolution, backed by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, came in response to an Iraqi refugee burning a Quran outside a mosque in Stockholm. Muslim protestors in Iraq made their dissatisfaction known by storming the Swedish embassy and, seemingly without irony, burning Swedish and LGBT pride flags.

Book burning is an unedifying spectacle – better to combat an idea with reasoned critique than destruction – but freedom of expression ceases to be meaningful if it only protects those acts we agree with.

And by accepting the physical sanctity of a religious text, we begin to accept the sanctity of the dogmas therein, many of which fly in the face of liberal values and are contemptuous of human rights.

It would be a mistake to think this is a far-flung issue. Blasphemy laws, both official and de facto, are alive and well here in the UK. Earlier this year, a 14 year-old autistic pupil in Yorkshire received death threats after a Quran he brought into school was dropped and scuffed. With local councillors and imams baying for blood, the student was suspended and issued with a non-crime hate incident by the police.

And in a chilling echo of the beheading of Samuel Paty, a teacher at Batley Grammar School was driven into hiding after he showed students a caricature of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The school prostrated itself before protestors, offering a "sincere and full apology" for the "great offence" caused.

When we as a society cede ground on seemingly less important issues – take, for example, allowing religious extremists to cancel the film The Lady of Heaven – we lose our appetite for the fights that matter most. To quote the Home Secretary: "Timidity does not make us safer; it weakens us."

We are 'lucky' that in the UK, blasphemy-motivated murders are rare (although they do occur). But we cannot and should not take this for granted. We need only look across the Channel to the attack on Charlie Hebdo to appreciate the blood-stained zeal with which fundamentalists treat blasphemy. Indeed, a newly published Henry Jackson Society report warns anti-blasphemy actions in this country could "inspire intimidation, violence and even mass killings".

So let's stand united for freedom of expression and oppose notions of blasphemy in all its forms.

Image by Anderson Menezes from Pixabay

Taxpayers shouldn't be burdened with propping up the Church

Faced with dwindling congregations, the Church of England is looking for ways to fund the growing repair bill of its aging buildings. Could your taxes be the answer?

Quite possibly, yes. Because the Church has successfully lobbied the government to allow more money to flow from cash-strapped local authorities to places of worship.

Using her seat in the House of Lords to further the Church's interests, the bishop of Bristol Vivienne Faull argued that legal uncertainly was preventing parish and town councils from funding church repairs.

The uncertainty stems from two conflicting bits of legislation – the Parish Councils Act 1894, which says that funds cannot be given to churches, and the Local Government Act 1972, which says that they can.

Now, faith and communities minister Baroness Scott has added an amendment to the Levelling Up Bill which will abolish a clause in the 1894 act to make clear that local authorities can fund churches and other places of worship.

Many churches hold historical and architectural significance. Few would want to see them fall into a state of disrepair. But who should foot the bill for their maintenance? Before any public money is spent, questions need to be asked about whether the organisation responsible for their upkeep has the means to do so.

England's 16,000 Anglican places of worship are the responsibility of the Church of England. The CofE is one of the largest private landowners in the UK and sits on £10.3 billion investment fund. Its assets were estimated in 2016 at £23 billion, since when the fund has grown by £3.6 billion.

Speaking in the House of Lords, Lib Dem peer Paul Scriven argued that if any of the Acts should be withdrawn, it should be the 1972 Act, not the 1894 Act. When it comes to maintaining religious buildings "the first port of call should be the reserves which the Church of England holds", he argued.

This view was echoed by Baroness Lorely Burt, who suggested more state subsidies would be an "inappropriate use of taxpayers' money" given the "extreme wealth" of the Church of England.

Despite its significant wealth, the CofE frequently pleads poverty. Due its fragmented financial and organisational structure, the Church can hide its money in plain sight, leaving many parishes in dire financial difficulty and struggling to afford repairs.

But the CofE can certainly find money when it wants to. Between 2017 and 2020, £248 million was allocated to evangelism as part of the Church's (so far unsuccessful) efforts to attract new worshippers. This has included splashing the cash on 'planting' new churches, hiring 'social media pastors', converting a nightclub in Bradford into a church with a gym to attract students, and recruiting children and young people's 'mission enablers' to "bring Christ to young people".

This year it also announced a £100m fund to make reparations for its slave trade links. And in a bid to tempt couples back to church weddings (which fell by half between 1999 and 2019) the Church has just voted to trial dropping its £500 fee for weddings. So, while lobbying for easier access to public funds for church buildings, the church is turning its back on a reliable source of income.

Churches, like any other organisation, should be responsible for their financial sustainability.

The Church of England received £750 million of public money between 2016 and 2021. This level of reliance on government funding risks creating dependency and discouraging financial accountability.

Britain is no longer a majority Christian nation. Fewer that 1% of the English population attend Anglican services on the average Sunday. With emptying pews and ageing congregations, the Church needs to face up to reality and downsize to survive. Until it learns this lesson, taxpayers shouldn't be further burdened with propping up an ailing yet wealthy religious institution.

As well as the practical reasons for resisting state grants to religion, there is also an important one of principle. Taxpayers at odds with the Church's doctrine and those it discriminates against, such as same sex couples who aren't even permitted to marry in their churches, may well have reasonable objections to their money funding a religion they reject. Providing financial support to religious institutions blurs the lines between the government and religions and undermines the state's commitment to treating all citizens equally.

So, when local churches come knocking for local authority grants, councils should remind them of the Church's wealth and refer them back to their powers above.

Image: UKgeofan at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

Don’t let the Church dictate how we marry

In justifying its uniquely privileged position as the established religion, the Church of England likes to portray itself as "an advocate for freedom of religion or belief". But its recent outburst on plans to liberalise wedding law tells a different story.

Last week bishop of Durham Paul Butler spoke out against the Law Commission's recommendations to reform wedding law in England and Wales, warning they are "likely to undermine the Christian understanding of marriage".

What are these proposed recommendations? They are to make our wedding laws simpler, fairer, and easier for anyone – of any religion or belief – to be married in a ceremony that's right for them.

Wedding laws in England and Wales are archaic. Different rules and restrictions apply depending on whether your wedding is Church of England, Jewish, Quaker, a different religion entirely, or not religious at all. If the wedding isn't Jewish or Quaker, you must get married in a building licensed for weddings. That strictly limits where most couples can get married, and there's no way to have a legally binding wedding ceremony led by an independent celebrant.

The statistics reflect the need to update wedding law. In 2019, marriage rates for opposite-sex couples fell to their lowest on record since 1862. Religious ceremonies accounted for less than one in five of opposite-sex marriages, the lowest percentage on record before the pandemic. These figures aren't too surprising since the 2021 Census revealed England and Wales are less religious than ever.

The Law Commission's proposals are designed to stop the decline in marriage by removing barriers to weddings suitable for people from all walks of life. They recommend streamlining the law so all weddings, whatever their religious or non-religious nature, take place according to broadly similar rules. Crucially, the 'buildings-based system' would be replaced with an 'officiant-based' one, meaning couples could get married anywhere provided the officiant was authorised.

This would greatly expand the possibilities of legally recognised weddings for religion or belief groups who don't tend to congregate or marry in dedicated buildings, including Muslims, Pagans and Humanists. The majority who want civil weddings would also benefit from having a much wider choice of venues, including "gardens, beaches, forests, parks, village halls and cruise ships."

Furthermore, the Law Commission has proposed a scheme for independent celebrants to become officiants and hold legally binding weddings. This makes sense; independent celebrants are in demand. Although the weddings they hold currently have no legal standing, there are at least 1,000 independent celebrants in England and Wales performing over 10,000 wedding ceremonies each year. The number of such ceremonies has more than doubled since 2015.

Wedding reforms would maximise freedom of religion or belief for all – especially if independent celebrants are included. They offer freedom for personal and spiritual expression quite unlike any other wedding provider. As Sophie Easton of the Association of Independent Celebrants says: "Many of the couples we work with are non-religious, but equally, many are spiritual in outlook, or in mixed-faith relationships, so it's our job to ensure their ceremony reflects them to a tee."

But the Church of England doesn't seem to like the idea of giving people the weddings they want, even if this would inherently deliver greater religious freedom.

Butler's fretting over the "Christian understanding of marriage" reveals the Church thinks weddings belong to them. They don't and they never did. Marriage institutions exist across cultures and religions – no single religion has a monopoly on weddings. It should be noted that the Church used this same argument in its opposition to legalise same-sex civil marriage.

Butler also argued that moves to "commercialise" weddings would lead to ceremonies that are not "dignified". This perhaps refers to the fact that for independent celebrants, holding weddings is their vocation and livelihood – they have to charge money for it.

The idea that allowing for greater choice in weddings would lead to 'undignified' weddings is scaremongering. The Law Commission has said the reforms are designed to "preserve the dignity of weddings" and said all officiants should be duty-bound to "uphold the dignity and significance of marriage". That Butler assumes the Church can do this, but other officiants can't be trusted to do so, may reveal the Church's own prejudice against heathens who dare to wade into what the Church thinks is its own territory.

And let's not forget the Church does charge a fee for officiating weddings; this can reach over £600. It is hypocritical for any religion or belief group to criticise independent celebrants for charging money for officiating weddings when they do the same thing.

What's more, every other aspect of weddings, from the venue to the catering to the clothing to the entertainment, is open to the free market. It seems entirely unreasonable to exclude the officiant alone.

So, what's the real reason for the Church's opposition to wedding reform?

Perhaps it's because allowing more groups and individuals to conduct weddings with far fewer restrictions will present significant competition to Church weddings, which are already in a drastic state of decline. In 2017, the average church only held one wedding that year, which isn't too surprising considering less than 1% regularly attend CofE services.

And while the Church's self-imposed ban on gay marriage remains, it cannot capitalise on same-sex weddings to bolster its numbers. No doubt many opposite-sex couples find the Church's homophobia distasteful, which puts them off marrying in a church too.

The Church's opposition to making it easier for others to hold weddings – weddings that don't have all the religious baggage of Church weddings – looks like petty protectionism. It knows it can't beat the competition, so it must discredit them.

The government is now considering the Law Commission's recommendations. The established Church, with all its privileged access to political power (as bishop of Durham, Paul Butler sits in the House of Lords), may put it under immense pressure to retain the unequal and restrictive status quo.

We can only hope the government can resist this pressure and reform the law based on principles of equality, fairness and freedom of religion or belief for everyone. The Church may not welcome that, but the British public would.

Faith schools foster unfairness and discrimination

Fairness and freedom should be central to state education. Recommendations from the UN child rights committee lay bare faith schools' failings, argues Stephen Evans.

On any given Sunday countless numbers of nonbelievers dutifully trapse off to church, not in search of sermons or salvation, but school places.

The bizarre phenomenon of parents attending church to secure a place at their local school stems from around a third of state funded schools being faith schools. Many of these may, when oversubscribed, give preferential treatment to children from families deemed sufficiently pious.

Faith-based admissions exist to ensure religious organisations running state schools can 'serve their own'. But the system also benefits the 'pew-jumping' middle class, who are willing and able to game the system by feigning faith to gain a place in a sought-after selective school.

It's often claimed that church schools deliver better academic outcomes. But the evidence shows that any educational advantages are small and are explained by factors around pupil intakes, such as religiously selective admissions arrangements.

Religious selection acts as a form of socioeconomic selection – and it's this, rather than a religious ethos, which compels many middle class parents to turn up at church to gain a place at a well performing school, without paying for a place at a private school. 'On your knees, avoid the fees', as the saying goes.

One such parent who admitted to doing this appeared on a local BBC radio debate I took part in last weekend. He explained that, unsatisfied with the schools in his catchment area, and unable to avoid private school fees, he attended services at an evangelical church once a month for five years to gain the necessary 'points' for a school place. He stopped going the moment his child's application was submitted.

That parents are willing to jump through such hoops to get their child into a particular school is a sad reflection on our state school system. Ideally, all children would have access to a good local school. By siphoning off the children from wealthier families at the expense of the rest, faith schools exacerbate the attainment gap between non-selective and selective education.

Gaming the system may be morally dubious, but rather than blame parents, we should reserve our indignation for a system that allows taxpayer funded schools to operate discriminatory admissions and select pupils on religious grounds.

The Equality Act exemptions that allow faith schools to give preferential treatment to worshippers legitimises faith-based discrimination. Thirteen years after the passing of landmark legislation to protect people from unfair treatment, religion's influence in state education is ensuring 19th century-style religious discrimination remains a feature of 21st century schooling.

Making religious leaders the gatekeepers to publicly funded services has other unintended consequences, too.

Whilst Church of England and Catholic schools usually require church attendance to gain the school's blessing, religious requirements in the oversubscription criteria of some minority faith schools' policies impose extreme religious ideology on families.

National Secular Society research revealed how some religious authorities use faith-based admission requirements to control how their students' families dress, whether they can use the internet, what they can eat, and even when they have sex.

Surely, it's time to consign this form of discrimination to history.

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) certainly thinks so. In its concluding observations to its latest periodic examination of child rights in the UK, the CRC called on the UK to guarantee the right of all children to freedom of expression and to practise freely their religion or belief, including by repealing archaic school worship laws and preventing the use of religion as a selection criterion for school admissions.

Those campaigning for a fairer and more inclusive school system often ignore faith schools and focus instead on grammar schools. The government has admitted it does not know how many schools apply religious discrimination in their admissions. But it's clear that far more school places in England are subject to religious selection than academic selection. So, if you want to achieve a fairer and more inclusive education system, faith schools are the obvious place to start.

That means standing up to entrenched religious interests by insisting the schools we all pay for are open equally to all children, without regard to religion or belief – and that they respect and protect all their pupils' freedom of religion or belief.

Despite the lack of evidence that faith schools do this any better than other schools, faith school enthusiasts like to wax lyrical about the values they instil in children – honesty, kindness, compassion, justice. But the values they actually entrench in society are privilege, unfairness, and discrimination.

One Conservative MP characterised the UN's recommendations as "intolerant" and an "attack on people and institutions of faith". Vested interests lined up to echo those sentiments. But tackling human rights violations and discrimination takes aim not at religion, but at the negatives that flow from organising public services around it.

A pluralist society should both tolerate and celebrate all forms of diversity, but that diversity should be represented within schools, not be a marker of division and a basis for educating and segregating children.

Adopting the UN child rights committee's recommendations would go a long way to putting things right.

Image: Rawpixel.com, Shutterstock

It’s religion’s critics, not believers, who are being pushed out of politics

Christian politicians have recently claimed they cannot talk openly about their faith. Megan Manson says recent events show politicians who criticise religion are far more likely to be silenced.

At a recent discussion hosted by religious think tank Theos, evangelical Christian Miriam Cates MP (pictured) lamented that it is "incredibly difficult" for politicians to talk openly about faith.

Cates was referring to Kate Forbes MSP, and her failed bid to succeed Nicola Sturgeon as leader of the Scottish National Party – and first minister of Scotland. Forbes has also given a recent BBC interview where she echoed the sentiment that religious people are being forced out of politics.

Cates asked the room: "Which part of the Christian religion is so hideous to people now? Is it helping the poor?"

It was a disingenuous question that conveniently ignored what the public actually find so concerning about Forbes: the views of the church she belongs to, the Free Church of Scotland.

This is a fundamentalist church which has opposed abortion, gay marriage, and children playing on swings on Sundays. Most people would consider these to be controversial positions to say the least. It is perfectly reasonable for the public to question a politician who belongs a group which espouses such views, religious or not.

As it happens, the leadership went to a Muslim, Humza Yousaf. If the highest seat of office in Scotland can go to a member of a conservative religion, surely that's evidence enough that the public doesn't find faith as off-putting as Cates makes out.

Nevertheless, Cates is right – it is difficult for politicians to talk openly about faith.

But perhaps not in the way she meant.

Within the space of a month, we've seen two politicians pushed out of their role for talking about religion. More specifically, for criticising religion.

In May, councillor Mike Gilbert was refused the mayoralty of Boston Borough Council because of Facebook posts in which he condemned Islam's stance on homosexuality and women's rights. The comments were made during the football World Cup hosted by Qatar, which at the time prompted widespread public debate about the human rights record of Qatar's Islamic regime.

The serving mayor implied Gilbert's legitimate criticisms were "hate speech" during the council's annual general meeting and told other councillors that failure to condemn such speech could be interpreted as expressions of "approval or support".

And this month, in an eerily similar case, Neyland town councillor Andrew Lye was stripped of his mayoralty after a blog he wrote in 2008 came to light, in which he questioned the religious circumcision of babies. It should be noted over 60% of Brits would support a law against non-medical circumcision of boys - a painful, permanent and non-consensual procedure which can have serious complications, including death.

Fellow councillor Brian Rothero called Lye's comments "nothing short of antisemitic and anti-Muslim". The council subsequently voted to remove Lye from the mayoralty. Lye has since resigned from the council.

Both cases spell grave danger for democracy and free speech. It only takes the silencing of one politician to silence them all. The message is clear: don't criticise religion, or you'll lose your job.

If politicians can't raise concerns about the human rights of gay people, women or children where religion is involved, what does that mean for the future of those human rights?

Religious fundamentalists are highly motivated to make it difficult for outsiders to talk honestly and critically about their religion. The all-party parliamentary group on British Muslims have aggressively pushed for institutions including local councils and political parties to adopt their definition of 'Islamophobia'. Organisations including the National Secular Society have warned the definition, which easily conflates criticism of Islam with anti-Muslim bigotry, would chill free speech and conflict with equality law. The recent incidents at two local councils prove this point all too well.

While local councillors are forced from their jobs for challenging the more egregious aspects of faith, religion (and especially Christianity) basks in a privileged position at all levels in government. As the established church, the Church of England enjoys unparalleled access to our head of state and the houses of parliament. It even has 26 bishops appointed to the House of Lords as of right, all of whom have full voting rights and are generally given deference during debates. Sittings in both houses open with prayers – as do many council meetings.

This is hardly an environment where religion fears government. As recent cases demonstrate, the opposite is true.

Cates did make a surprisingly secularist point during the discussion, however. Defending Forbes, she said: "There should be a separation between personal faith and what happens in a democracy".

It is heartening to see an understanding here that separating the democratic process from personal religion is key to protecting everyone's freedom of speech and freedom of conscience, whether religious or not.

But it's a process which goes both ways. Just as religious people should be free to express their beliefs, others shouldn't be afraid to criticise them.

And the best framework for this is a secular democracy, where religion is neither privileged nor disadvantaged, and just one of many stalls in the marketplace of ideas.

Why are councillors doing Islamists’ work for them?

After a councillor was denied mayoralty for criticising Islam, Jack Rivington warns politicians are playing into the hands of Islamist fundamentalists.

Last week, members of Boston Borough Council decided that the principle of free expression, and the traditions of their mayoralty, were less important than potentially offended religious feelings.

By convention as the longest serving member, Councillor Mike Gilbert was due to be appointed mayor of Boston for a one year term. However, following an intervention by several fellow councillors, he was blocked from taking up the position last month on the grounds that he had made past comments criticising aspects of Islamic religious doctrine.

These comments, posted on social media during the football World Cup in Qatar, drew attention to several features of Islam which Cllr Gilbert considered to be in conflict with the rights of women and LGBT people. Namely that in Islam, homosexuality is punishable by death, and women are considered to be of a lower status than men.

Despite Cllr Gilbert very clearly stating that his criticisms were not of Muslims themselves but of particular religious doctrines, a number of borough councillors saw fit to denounce him for what they characterised as 'hate speech'.

Cllr Anne Dorrian, who was serving as mayor at the time, said councillors had a political and moral obligation to "refrain from using hate speech". Failure to condemn such speech, Cllr Dorrian warned, could be interpreted as expressions of "approval or support". Cllr Dale Broughton also criticised the remarks, saying that they did "little to bring about social integration" in Boston.

It's disappointing that our elected representatives don't consider themselves at least equally obligated to defend the right to freedom of expression, integral as it is to our democratic society, or to advance the cause of secularism, which is the best guarantee of social cohesion and integration that we know of.

Through their actions, the councillors have signalled that religion, and in particular Islam, should be beyond the realm of reasonable public debate. Although attempts by religious fundamentalists to impose blasphemy codes and suppress freedom of expression around Islam are so regular as to no longer be surprising, it is alarming to see UK politicians so readily line up to support the same cause.

No argument was presented by the councillors as to why the comments were hateful, or indeed factually incorrect. Cllr Gilbert's concerns were simply deemed unmentionable, remarks which should not have to be read, tolerated, or thought about. Cllr Gilbert's name has been unfairly smeared, and those responsible can't even be bothered provide an explanation.

Is there any justification for such censorship which does not involve the claim that criticism or even discussion of ideas amounts to a personal attack on individuals? If applied to any non-religious ideology the ridiculous nature of this claim becomes apparent. Criticising the idea of a constitutional monarchy, for example, does not amount to a grave insult to the personal dignity of committed royalists – any claim that it did would be worthy of ridicule. There is nothing to justify religious viewpoints being treated any differently.

It is worth recalling the motivation of Cllr Gilbert's posts: to highlight injustices being done to women and LGBT people by those who employ Islamic doctrine as a justification. This, of course, includes people who are themselves Muslims, many of whom are engaged in their own battles against regressive religious dogma. By the logic of Boston's councillors, expressing solidarity with a significant proportion of the Muslim community is somehow hateful towards them.

Let us imagine that Cllr Gilbert's comments had instead been made by, say, an ex-Muslim lesbian. Would the councillors have disparaged and discounted them in the same way? If not, why not? Are the comments themselves hateful, or are they only hateful in virtue of being spoken by a particular kind of person?

Following the council meeting, Cllr Gilbert was invited by the imam of Boston's mosque, Abdul Hamid Qureshi, to a meeting where they could discuss his "assumptions", which he described as "speculative rather than factual" and "out of context and selective". Irritating and patronising though this is, the opportunity for dialogue should be welcomed. It would be nice if Mr Qureshi could also make clear his position on the supposed 'hateful' nature of Cllr Gilbert's remarks, or defend the right to freedom of expression despite his disagreement with what was said.

The people most likely to be grateful to Boston's councillors are religious fundamentalists, who now don't even have to kick up a fuss for free speech to be suppressed. As Boston's councillors have made clear, there's enough useful idiots who are willing to do it for them.

Thanks, but no thanks: the US can keep its culture war

American efforts to export regressive religious views under the guise of the 'culture war' are to be resisted, argues Alejandro Sanchez.

President of US conservative thinktank The Heritage Foundation, Kevin Roberts, is a man on a mission. A keynote speaker at this year's National Conservatism (NatCon) conference in London, he bemoans the reticence of the British right to engage in "what we Americans call the culture war" – a struggle between groups with opposing and entrenched ideologies to dictate public policy. He now seeks to stoke the flames of social division here in the UK.

This should come as no surprise. Back home, Roberts champions a crusade against "woke totalitarianism" underpinned by "faith, family, freedom, and nation." And he speaks openly of his desire to overturn the constitutional right to same-sex marriage in the US, describing it as "a really bad social experiment that we're only beginning to see the rotten fruit of".

The "political success" of Florida governor Ron DeSantis, he claims, serves as a shining example of what can be achieved by harnessing the power of the culture war. And what is this success, exactly? A six-week abortion ban and the Protections of Medical Conscience Act, which allows doctors to deny gay patients treatment on the basis of a "sincerely held" religious belief.

Call me a cynic, but the spoils of Roberts' culture war and the long-standing goal of Christian nationalism – to impose conservative Christian values on our political life - seem curiously aligned. This thinly veiled rebrand makes perfect sense in the British context: for the first time in the history of the census, we are now a minority Christian nation. Theological invocations simply will not wash with the public.

Instead, religious objections to women's and gay rights are being repackaged and masqueraded as part of a broader backlash against 'wokeism'. This is not to say there are no legitimate criticisms to be made of the excesses of the left, only that regressive religious agendas should be recognised for what they truly are.

The Edmund Burke Foundation, the American organiser of NatCon, is even less subtle. Public life "should be rooted in Christianity", it says. And the "lifelong bond between a man and woman" is "the foundation of all other achievements in our civilisation". No prizes for inferring the logical conclusion of that.

Fellow speaker and evangelical Christian Danny Kruger MP said the quiet part out loud: heterosexual marriage, he proclaimed, is the "only possible basis for a safe and successful society". And though his naked homophobia was rightly rejected by the government, if the rise of Trump and attendant US Christian nationalism has taught us anything, it is this: when someone tells you who they are, believe them.

To the extent that the culture war is characterised by bad faith arguments, deliberate efforts to polarise, and the promulgation of echo chambers, it is to be opposed. Instead, we should aspire to reasoned criticism of opposing views and unsparing self-examination of our own.

In closing, I draw on the warning of NatCon's own James Orr. He implored fellow conference-goers to shield British children from the "norms and narratives from our cultural colonial overlords in the United States". We should take his advice one step further, and reject the American culture war wholesale.

Hold the Church to account for abuse – separate it from the state

The Church of England's increasingly dire record on safeguarding should have consequences for its established status, says Megan Manson.

It didn't take long for the glitz and glamour of the coronation to fade, and for the Church of England to find itself back in the quagmire of abuse scandals.

Within days of their Westminster Abbey extravaganza, the UK's established Church found itself having to answer to damning findings of an independent review into the case of Trevor Devamanikkam, a CofE priest who raped Matthew Ineson in the 1980s. Ineson was just 16 years old.

Days later, victims of alleged abuse at the hands of CofE preacher Mike Pilavachi called for an independent investigation into his actions, as they don't trust the Church's own internal inquiry.

Pilavachi's victims and survivors have every right to be sceptical of the Church's ability, in their words, to "mark its own homework". The Devamanikkam review, and responses from those implicated, make plain why.

The review paints a picture of a chaotic and bumbling Church, unclear of what to do when safeguarding disclosures are made and incapable of providing important paperwork relating to the case in a timely manner (if at all).

But most troubling of all are the bishops who failed to act despite Ineson, himself now a CofE vicar, making multiple verbal and written disclosures of abuse. Bishop of Oxford Steven Croft (pictured; left) and retired archbishop of York John Sentamu (right) in particular stand out. Both of them sit in the House of Lords thanks to the unique CofE privilege of having 26 seats reserved for their bishops. Croft is a current member of the bishops' bench and Sentamu is now a Lord Temporal; all former archbishops of Canterbury and York are offered life peerage.

Croft has admitted his inaction was wrong and, 10 years after Ineson's disclosure, has finally apologised. Ineson, not unreasonably, has called for Croft to step down: "You cannot ignore disclosures of rape by a priest and do nothing."

But Sentamu's reaction has been quite different. Let's not forget he was archbishop of York at the time of the disclosures – second only to the archbishop of Canterbury in the church hierarchy. He was copied into Ineson's letter disclosing the abuse to Croft in 2013. In any place of work, you would hope a safeguarding issue, especially one raised by a current employee, would be taken with the utmost seriousness by senior management. But Sentamu's only action was to reply to Ineson: "Thank you for copying me into the letter, which I have read. Please be assured of my prayers and best wishes during this testing time."

The review rightly criticised Sentamu for failing to use his authority to ensure Croft responded to Ineson, or to write to Ineson directly, or to seek advice from his Diocesan Safeguarding Adviser, instead of merely sending 'thoughts and prayers'.

Unlike Croft, Sentamu's reaction to the review was not to admit wrongdoing, but to double down. He said the reviewer's conclusion that no church law "excuses the responsibility of individuals not to act on matters of a safeguarding nature" is "odd and troubling". He even made the extraordinary claim that "Safeguarding is very important but it does not trump Church Law".

Sentamu appears to be incorrect; the review concluded Sentamu failed to act according to the Church's own procedures. But his statement is not only wrong – it reveals the extremely warped sense of moral priorities that many Church leaders operate under. If a church's rules meant a victim of child sexual abuse could not get justice, surely a moral person could not tolerate being a leader within that church?

Sentamu has since been asked to step down from his CofE role while the Church considers the review. But he is by no means the first CofE leader to seemingly prioritise institutional agendas over the safety and wellbeing of children and young people. Consider the case of bishop Peter Ball, whose victims of abuse were branded liars by the Church while Ball was afforded all sympathy and support – even from former archbishop of Canterbury George Carey and then-Prince Charles, who is now the Church's supreme governor.

Even former culture secretary Nadine Dorries MP, not usually a sceptic of faith groups, has criticised the Church's response to the Devamanikkam case. She was abused as a child by an Anglican priest but was met with "silence" when she disclosed what happened to her, and probably to other young girls, to bishops in the House of Lords. She rightly asks: "How many more of us — people like Matthew Ineson and myself — are there out there? People who were abused as youngsters and then ignored."

She adds: "The Roman Catholic Church has, with good cause, been the focus of much of the historic child sex abuse in recent decades, and that has suited the Church of England. But it cannot escape the evil that lurks within its own cloisters any longer."

But what is the state's response to the Church's failures on child abuse?

Very little, it seems. The Church continues to sit comfortably in the constitution as the state religion, luxuriating in the status and privilege this brings. Its bishops, even those at the heart of safeguarding failures, continue to sit in the House of Lords as of right. Our head of state must pledge to uphold the Church's privileges at an Anglican ceremony costing millions in taxpayers' money – as we speak, plans for William's coronation are already afoot. The Church is allowed to lead prayers at the start of every sitting in both houses of parliament. And it controls over a quarter of all primary schools, making it the largest academy provider in England. Hardly a responsibility we'd usually grant an institution with such an appalling record on child abuse.

The Church uses its supposed 'moral insight' to argue for its privileges. Its record on sex abuse surely shatters this argument – together with its increasingly outdated institutional homophobia and sexism.

Survivors and campaigners rightly call for a zero-tolerance approach from the Church of England towards abuse. But this responsibility should also apply to the UK state. If we want to demonstrate we take protecting children from abuse and justice for victims seriously, we must show there are consequences for institutions that repeatedly fail in safeguarding. That should include stripping the Church of its exclusive, unearned and increasingly unjustifiable privileges as the state religion.

Image: Roger Harris, CC BY 3.0

The 2015 General Election

Response unit needed to tackle blasphemy flashpoints, report says

Recommendations echo NSS calls for more support for schools facing religious intimidation and threats.

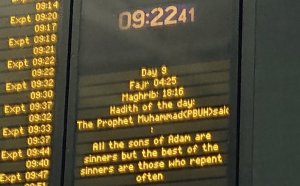

NSS welcomes Network Rail decision to remove religious messaging

Following NSS criticism, Islamic hadith calling for 'sinners to repent' removed from departure board at King's Cross station.

NSS slams government for backtracking on non-stun slaughter labels

Defra consultation on "fairer food labelling" omits slaughter, despite 97% supporting labels for slaughter method.

Experts speak out against religious abuse

Public authorities failing to tackle abuse in religious settings, panellists say at NSS event.

Majority of public support removing Isle of Man bishop’s vote

Most Manx residents back removing prayers and votes for clerics from parliament.

NSS address urges UN to call for government action on human rights

Religious privilege is undermining rights of UK citizens, NSS tells UN committee.

Anti-blasphemy extremism “gaining momentum” in UK, report warns

Counter-extremism report recommends review of religious charities linked to anti-blasphemy activism.

New extremism definition may put free speech at risk, NSS warns

Proposed definition could 'label secularists as extremists'.

A state Church is no bulwark against extremism – but secularism is

With its commitment to the separation of religion and state and safeguarding the rights of all individuals, secularism can provide an effective defence against the spread of extremism, says Stephen Evans.

Iranian support for secularism has more than doubled since 2015

Iranian support for secularism has more than doubled since 2015