The continued effort to silence Charlie Hebdo is shameful

Posted: Fri, 18th Sep 2020 by Chris Sloggett

It is outrageous to try to force this small magazine to give the 2015 killers what they wanted, says Chris Sloggett.

Earlier this month 14 people went on trial over the 2015 attacks on the offices of Charlie Hebdo.

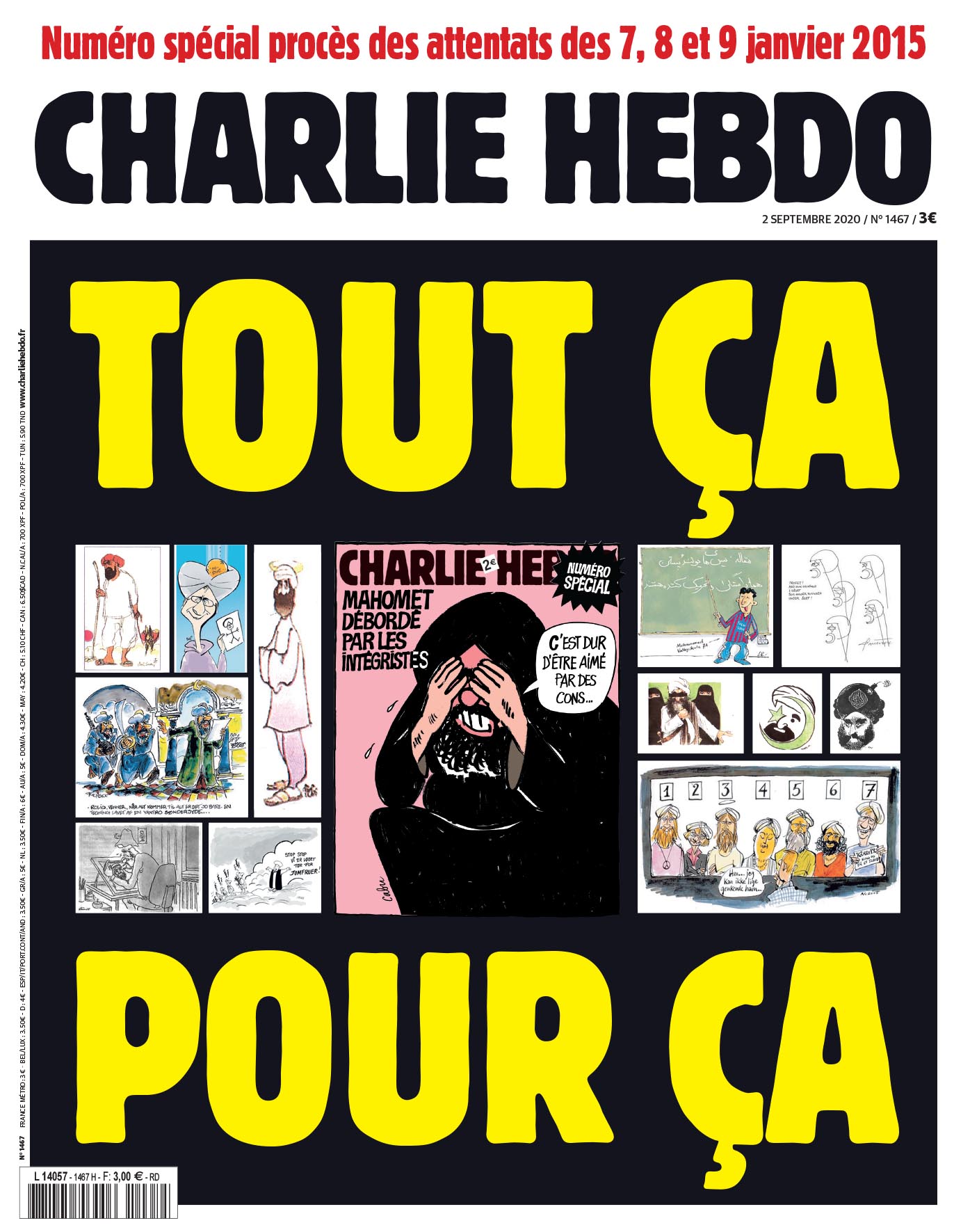

The magazine, unsurprisingly, considered this worth a front page response. Alongside a set of cartoons featuring Islam's prophet Muhammad came a simple message: Tout ça pour ça (All that for this).

This wasn't just a legitimate editorial decision; it was also entirely understandable. A trial focused on the killings of Charlie's staff was opening, and the surviving staff used the magazine's front page to comment on it. That included reprinting the cartoons that their colleagues died for.

But predictably, it was followed by a flurry of pearl-clutching. The government of Pakistan – where a man was sentenced to death for sending 'blasphemous' text messages just last week – quickly condemned Charlie's decision in "the strongest terms". People there, and in countries including France, Nigeria, Indonesia, Iran, Chechnya and Yemen, took to the streets to protest.

A craven opinion piece in Al-Jazeera asked: "If it is easy enough to understand why some Muslims respond violently to derogatory tropes about Islam, the prophet and the Quran, what does it say about those who compulsively keep recycling these?"

Meanwhile in Britain, the headlines of stories on the BBC and the Independent, and the top line of a Guardian report, again told us the cartoons were "controversial". This was true, of course, but also very much beside the point.

We were also treated to a curious intervention from Qari Asim, an imam at a mosque in Leeds and – more importantly – the government's adviser on 'Islamophobia'.

You may recognise his name. Earlier this year The Sunday Times reported that there were calls for him to step down from his advisory role, amid criticism of comments he'd previously made about free speech. He'd suggested some Muslims want exceptions to free speech where they find it "distasteful". His supporters vociferously defended his comments, and his critics' case was left looking flimsy.

The following month he secured an apology from the Mail on Sunday and Mail Online, which had falsely accused him of supporting the hanging of the Christian woman Asia Bibi in Pakistan.

But his response to Charlie Hebdo's decision to republish the Muhammad cartoons was, to put it lightly, questionable. In a deeply confused, rambling letter to The Independent, he wrote that it was "disgraceful to see Prophet Mohammad being used in such a derogatory way" and described the magazine's decision as "deliberately insulting and offensive".

He went on to say Muslims should not be scapegoated as terrorists; Muslims respect freedom of speech "but not when it incites hatred"; and people shouldn't play into the "hateful rhetoric" of extremists. The relevance of these points to Charlie's decision to republish – the subject of the letter – was left unclear (at least in the published version).

It's also worth noting the similarities between his language and that used in Scotland's current hate crime bill. The bill would criminalise expression which is "threatening or abusive" and intended or "likely" to 'stir up hatred' on the basis of religion. It's legitimate to ask – as The Spectator's Stephen Daisley, Murdo Fraser MSP and the NSS's own Stephen Evans have – whether those who publish Charlie's cartoons could be prosecuted under the bill.

But even absent of criminal sanction, the ongoing rows over Charlie Hebdo are deeply disturbing. It's bizarre to see so many people trying to appoint themselves as editorial advisers to a small French magazine which many of them probably hadn't even heard of until its staff were gunned down. And it's deeply shameful to see them trying to use that position to tell the magazine to bury the work of the dead with their bodies.

There is a straightforward option for those who dislike the cartoons but who also respect the right to publish them. When they were republished this month the head of the French Council of Muslim Worship, Mohammed Moussaoui, urged people to ignore them. The council itself responded by condemning terrorism and tweeting: "The freedom to make caricatures and the freedom to dislike them is guaranteed and nothing can justify violence."

This is correct, and it shouldn't be difficult. People are free to dislike Charlie's cartoons, and to say so. But in this context the obsessive, utterly disproportionate outrage at a small magazine's decision to publish a few drawings represents an attempt to create a climate where those drawings can't be published at all.

We should say again that it's outrageous to try to force the survivors of this massacre to give those responsible for it what they wanted. At the very least these people could leave Charlie alone to stick two fingers up to those who slaughtered its staff.

What the NSS stands for

The Secular Charter outlines 10 principles that guide us as we campaign for a secular democracy which safeguards all citizens' rights to freedom of and from religion.