Five years after the Charlie Hebdo murders, free expression on religion still needs promoting

Posted: Tue, 7th Jan 2020 by Chris Sloggett

Half a decade after the Islamist attack on cartoonists in France, Chris Sloggett says we owe it to the victims and those left behind to reject blasphemy taboos.

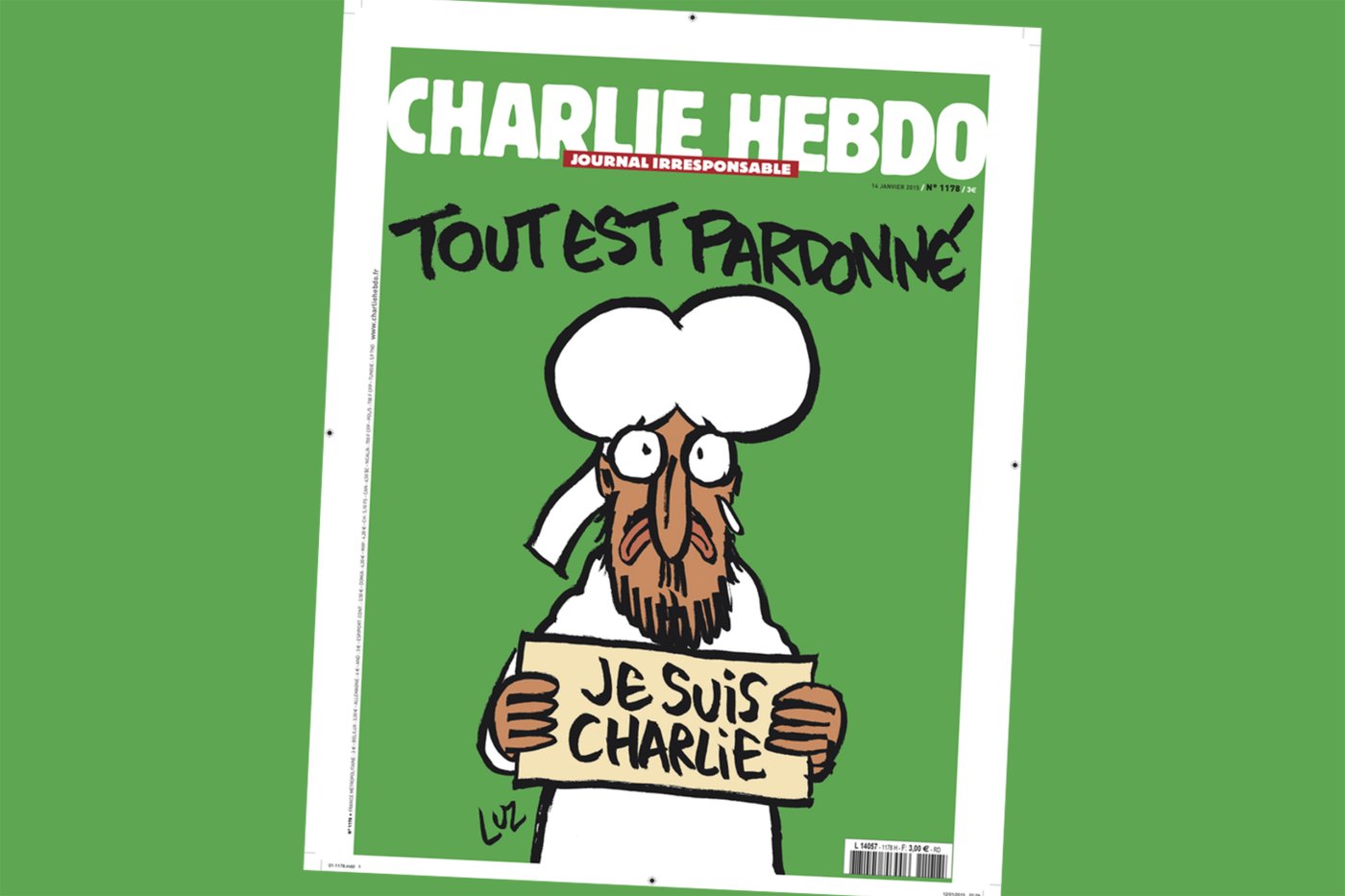

Five years ago today two Islamist gunmen walked into the office of the small satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo, shot dead 12 people and declared they had "avenged the prophet Muhammad".

In response politicians from around the world marched in Paris, supposedly in defence of free expression – leaving themselves open, in some cases, to charges of glaring hypocrisy. Meanwhile the phrase 'Je suis Charlie' became ubiquitous on social media. But this wasn't enough to convince leading publications to reprint Charlie Hebdo's work widely, and the taboo on depicting Muhammad remained largely in place.

So the actions of world leaders and ordinary social media users represented little more than statements of sorrow at the atrocity and expressions of solidarity with the victims. Even so, some saw them as too supportive. With the victims freshly unable to defend themselves, some mainstream commentators quickly and shamefully hung them out to dry. It proved remarkably acceptable to push unsubstantiated and highly selective critiques of the victims' work, and effectively demand it be buried with their bodies.

Half a decade on, there have been some small signs of progress. Over the Christmas break Ireland officially repealed its blasphemy law, following a referendum in 2018. Since 2015 seven other liberal democracies have done the same, giving an official nod to the fact that there's no right to stop someone criticising your religion. (It's worth noting that Scotland and Northern Ireland still retain blasphemy laws.)

But blasphemy laws remain the source of grave injustice and even deadly threat across much of the world. A recent report from Humanists International found that 69 countries have blasphemy laws on their books. Eighteen countries outlaw 'apostasy'. In 12 of them it's punishable by death. And people can effectively be put to death for expressing atheism in 13 countries.

Less than three weeks ago the academic Junaid Hafeez was sentenced to death for blasphemy in Pakistan. He joins around 40 people currently on death row for this non-crime in the country. Meanwhile the UK government, when questioned about Pakistan's blasphemy laws, only critiques their 'misuse', as it regularly and diligently avoids any criticism of their existence. The National Secular Society raised concerns about this with the Foreign Office last year, and received a bland response which didn't address the points we put forward.

The Charlie Hebdo murderers didn't use the law to enforce their blasphemy taboos: they preferred to try extra-judicial terrorist violence. That tactic could easily be used again, and not necessarily only by Islamists. Two weeks ago the office of a Brazilian comedy group which had depicted Jesus as gay in a TV show was firebombed, with a far-right group claiming responsibility. The echoes of the firebombing of Charlie's offices in 2011 were alarming. (Update, 10 Jan: since this blog was published a Brazilian judge has ordered Netflix to remove the show and that decision has quickly been overturned by the country's Supreme Court).

Some have tried to drum up outrage or threatened economic consequences against those who criticise or mock their religious outlook. In recent weeks Christian and Muslim petitioners have sought to prevent the new Netflix show Messiah being broadcast on the basis that it's 'blasphemous'. The methods may be different, but these are still attempts to weaponise religious identity to prevent the criticism of ideas which bullies hold dear.

Then there are softer but perhaps more pervasive forms of censorship. A society which gives free speech on religion the value it deserves should seek to ensure all religions are fair game for mockery, and criticism of it is as ordinary as criticism of any other set of ideas. But the victim-blaming that followed the Charlie Hebdo attack highlighted how difficult it is to bring criticism of religion away from the fringes of public conversation.

We still need to be vigilant of this. Over the last 14 months many political parties, local authorities and public bodies have adopted a censorious definition of 'Islamophobia'; the government has come under pressure to follow suit. The parliamentary group behind the definition dismissed or failed to engage with concerns about the erosion of free speech on Islam, and has spoken approvingly of efforts to prevent "reckless" speech on it. Is that the language that would be used to smear another Charlie Hebdo?

Five years on from the Charlie attack, it remains remarkable that merely showing solidarity with the victims became controversial. But the fact it did, and the energy that free speech defenders had to spend pushing back against the apologists, risks blinding us to the fact there was harder work to do.

That work is ongoing. And it involves not only defending, but actively promoting, the principle that was under attack that day. We owe it not only to the victims but to those left behind – whatever our personal religious outlook or affiliation – to stand for free expression on religion.

While you're here

Our news and opinion content is an important part of our campaigns work. Many articles involve a lot of research by our campaigns team. If you value this output, please consider supporting us today.