The British people deserve better than the fawning over Michael Curry

Posted: Thu, 21st Jun 2018 by Chris Sloggett

As a poll shows public ambivalence to a much-hyped sermon at the royal wedding, Chris Sloggett says the fuss around Michael Curry has distracted from an opportunity to ask critical questions about religion's public role.

In March the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse spent three weeks hearing evidence about the Church of England's handling of abuse in just one of its dioceses, Chichester. The inquiry heard of institutional cover-up and collusion with abusers. It heard that church doctrine, and its historic opposition to homosexuality and female bishops, may have fuelled the abuse. Meanwhile, as if it were a casual aside, there were reports that both the archbishop of York and a former archbishop of Canterbury could face police investigation for covering up sexual abuse.

But no matter what the C of E does, it can usually find an unearned good news story from somewhere. Last month's wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle was technically a private event. But thanks to the fawning and disproportionate media coverage it generated the wedding became, de facto, a major free advert for the established church that hosted it.

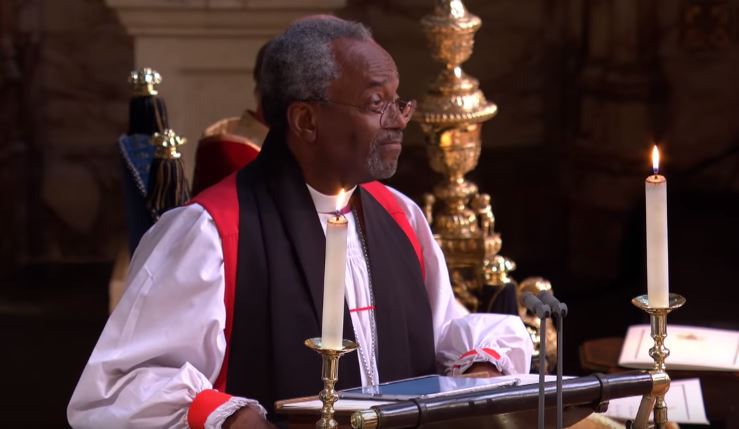

And if you believe much of what you read, Britons were apparently enraptured during the wedding by a sermon delivered by Michael Curry, an American bishop in the Episcopal Church. The supposedly republican press united with the royalist to reinforce this message. The Observer and Sunday Times led their front pages the following day with Curry's words: "Two people fell in love and we all showed up" (it was unclear to which 'we' the papers were referring). The Mail called Curry's sermon "powerful". The Express said he "stole the show".

And if you were expecting the Guardian to challenge hereditary privilege or the cosy relationship between church and state, you could forget it. Opinion writers put identity politics before genuinely liberal principles, telling us the sermon would "go down in history" and had "swiftly and decisively answered" any doubts about the speaker's influence.

The Washington Post said the wedding had made Curry a "superstar". And in the last month that, at least, has borne true. Curry has given a special Christian blessing to open the final of Britain's Got Talent, appeared on the Today programme and Good Morning Britain and featured on several US TV shows.

The C of E has jumped at the chance to enjoy a bit of positive coverage. After the wedding the archbishop of Canterbury posed with Curry, saying his sermon "blew the place open". The Today programme's interview with Curry focused on "making the Church of England less boring".

But the British public doesn't seem to be buying it. According to a new poll from ComRes, on behalf of the Christian think tank Theos, just 16% of Brits said they would be more likely to go to church if the preaching was similar to Curry's. Only 12% thought the sermon improved their understanding of Christianity.

Just 22% said it was appropriate to mix religion and politics on occasions such as royal weddings. And even the warmest response – 34% of people said Curry's sermon had "expressed ideas that people can easily agree with" – was hardly a ringing vote of confidence.

Most of those who gave positive responses were already Christians. Thirty-one per cent of weekly church–attenders thought the sermon improved their understanding of Christian beliefs; just eight per cent of non–attenders agreed. Only 22% of those who didn't go to church thought the sermon's tone and content were appropriate for the occasion (as opposed to 55% of weekly churchgoers).

For many the sermon simply inspired a shrug of ambivalence. Sixty per cent of respondents, for example, were either unsure or indifferent about whether the sermon improved their understanding of Christian beliefs.

Many Britons seem to think the sermon was not as interesting or profound as it was made out to be. And if you watch Curry telling the audience "love is the way" for 14 minutes you may think they have a point. So why has the coverage implied so strongly that they were wrong?

For those whose job is to hold the powerful to account, the royal wedding was a chance to ask a series of critical questions – particularly about the role the established church plays in public life. Why do we have a state religion, why is our head of state also the head of the Church of England and why do those who marry in to her family effectively have no choice but to be baptised and married into that church? Why is this institution allowed to pose as our country's moral guardians when it has shielded sexual abusers?

Why does the church's grip on marriage laws in England and Wales make it significantly harder and more expensive to arrange a same-sex or non-religious wedding than a religious one? Why can the church tell people who reject its teachings what they may or may not include in their civil marriage ceremonies?

And do we really want our taxes to pay for preachers like Curry to tell our children what to think in the C of E's schools?

Instead we had puff pieces wondering whether the archbishop of Canterbury would drop the rings before the wedding and hype around Curry after it. The press largely abandoned its duty. No matter what harm religion may do, it seems we must find positive things to say about it.

But perhaps people in Britain are seeing through this and we have a chance to move the conversation on to territory which will make the C of E less comfortable. Next time the church spots the chance for an easy bit of positive publicity, we should be less willing to play its game.