Why make a spectacle out of religion in the courtroom?

Posted: Fri, 24th Jul 2020 by Stephen Evans

Stephen Evans argues that the current system of religious oaths and affirmations should be replaced by a universal secular declaration of the solemn duty to tell the truth.

The Republic of Ireland looks set to take another step towards secular modernity by removing a requirement for witnesses to indicate their religious faith when filing an affidavit.

The changes are being proposed in the Civil Law and Criminal Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill 2020, under which witnesses would instead make a "statement of truth".

However, as is the case in the UK, jurors and witnesses giving evidence in person in court will still be required to swear a religious oath or make a secular affirmation.

So, whilst the reforms in Ireland are welcome, they don't go far enough – as the president of the Law Society of Ireland, Michele O'Boyle, has pointed out.

Ireland's Law Society has been advocating for abolition of religious oaths since 1990. According to Ms O'Boyle: "The current system of oaths and affirmations, which dates back to 1888, is contrary to the right to privacy and contrary to a person's dignity in legal proceedings.

"Requiring a person to either declare one's religious conviction, or lack thereof, is, by any standard entirely inappropriate in a progressive, 21st century legal system." Quite right.

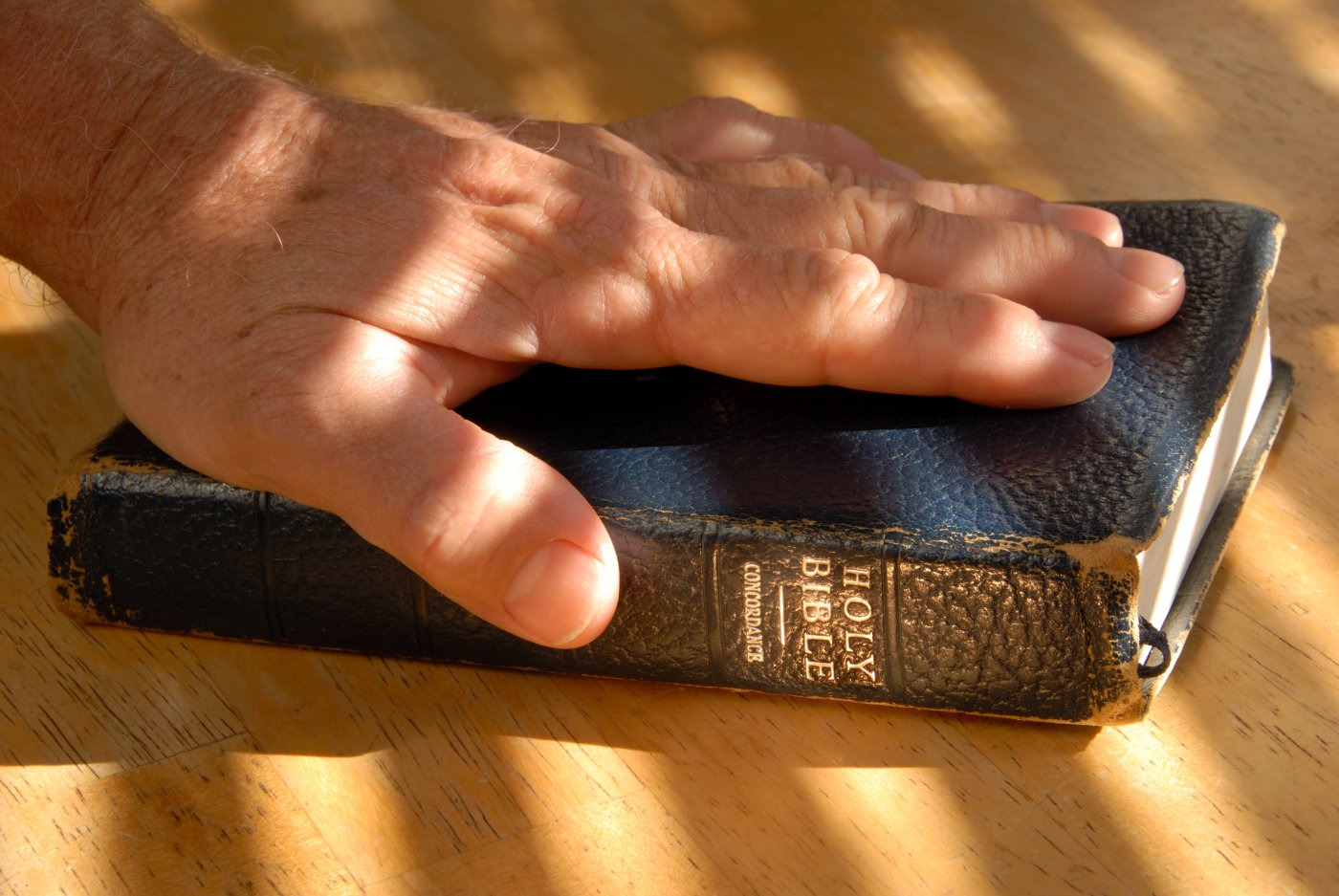

This system of different religious oaths on various holy books and secular affirmations unnecessarily makes an issue out of people's religiosity in the courtroom. Why on earth should a defendant's or witness's religious affiliations be the first thing a jury finds out about them?

An individual's religious beliefs are essentially a private matter and (usually) entirely irrelevant to the legal process. But there is also the risk that making a performative display of a person's religious or atheistic convictions may actually impede the administration of justice. According to O'Boyle, the current system of oaths and affirmations can "give rise to unfair perceptions on the credibility of the evidence given where individuals decline to take a religious oath".

This is backed up by academics, who have argued that a procedure that signals someone's belief or disbelief in God "is an influential cue of morality or immorality" that could bias trial outcomes in any number of ways.

According to Ryan McKay at Royal Holloway and Colin Davis, chair in Cognitive Psychology at the University of Bristol: "There is a real risk that defendants who take the religious oath when giving evidence may, by that very fact, enjoy more favourable verdicts and sentencing decisions than those who opt for the secular affirmation."

"The different potency of the religious oath and secular affirmation as signals of a witness's credibility is precisely the reason the oath should be abolished", they argue.

But it's not only the non-religious who stand to be disadvantaged. Any juror harbouring a prejudice may be influenced by someone swearing on a holy book, and regard them with suspicion, consciously or unconsciously.

A single affirmation to tell the truth, and acknowledgment that knowingly giving false evidence may result in prosecution for perjury, removes any unnecessary distinction between witnesses. It introduces a level playing field that takes away the need for a person to reveal their religious beliefs before they even give evidence. This would put all witnesses on an equal footing, making it more likely that cases would be decided on the evidence heard rather than the prejudices of those hearing it.

A proposal to end the swearing of oaths on the Bible and other holy books in courts in England and Wales was considered, but ultimately rejected by magistrates in 2013. The motion called for oaths and affirmations to be replaced by a promise to "very sincerely tell the truth". Magistrates Association members who backed it argued it would make the justice system fairer, more relevant and help to convey the importance of what witnesses are saying.

Senior figures in the Church of England called it "another attempt to chip away at the country's Christian foundations" and at least one who member who rejected the motion expressed concern that that magistrates would "pilloried for going against centuries of tradition". Church leaders also argued that religious oaths strengthen the value of witnesses' evidence. This argument, which has more than a whiff of prejudice about it, is as unconvincing as it is unsupported by evidence.

Some evangelicals would probably argue that to deny people the opportunity to swear on the Bible in court would restrict their religious freedom. But any person making a secular 'statement of truth' can of course privately call on God to witness the truth of their statements if they so desire. And any tension with human rights is created by a legal system that requires individuals to reveal personal beliefs. Replacing religious oaths and affirmations with a single declaration would best protect everyone's right to respect for private life, which is enshrined in Article 8 of the Human Rights Act.

There is a value in requiring witnesses to acknowledge publicly before they give evidence that they are under a solemn duty to tell the truth – and commit a serious criminal offence if they do not. But the process for achieving this should be universal, rather than the multifaith mishmash of oaths and affirmations we have now.

Tradition is all good and well, but it shouldn't stand in the way of a secular legal system which treats everyone equally and which prioritises the fair administration of justice above all.

While you're here

Our news and opinion content is an important part of our campaigns work. Many articles involve a lot of research by our campaigns team. If you value this output, please consider supporting us today.