It's not too late to fulfil George Holyoake's secularist vision

Posted: Thu, 30th Jul 2020 by Ray Argyle

With secularist principles under siege across much of the world, it's worth reconsidering the vision of the man who coined the term 'secularism' in the 19th century, says his biographer Ray Argyle.

This article is available in audio format, as part of our Opinion Out Loud series.

When I was a schoolboy in British Columbia we began our day by reciting the lord's prayer. I accepted this small duty as a normal ritual of the classroom. Then, two things happened. First, I asked one of my classmates to give me some evidence for the truth of stories in the Bible. He insisted they were true, but could offer no support for their veracity. Second, two members of the Jehovah's Witnesses sect arrived at my home one Friday after school. I was home alone. These emissaries had a powerful story and I was willing to hear it.

Over the weekend, I plunged into the literature they had given me. I was caught up in the exhilarating evangelism that Jesus Christ supposedly taught and that his apostles practiced. On Monday, I returned home from school anxious to resume my religious reading. Perhaps five or six hours of secular boyhood, or an instinctive scepticism about most of what my elders told me, brought everything into focus. I came to the jolting decision that all I'd been told or read over the weekend was not believable.

Later, as I examined more closely religious practices around the world I also learned about secularism, a practical system that fulfills the idea of separation of church and state by removing religious control of public institutions – the schools, courts, government, and all public endeavours.

While growing numbers in western countries are content to live outside the church, many people of faith also support secularism for its contribution to social order and its hands off attitude toward religion. But secularism's future, like the struggle to achieve it, is subject to the dynamics of public opinion and the pressures of social change. The most relentless opposition to secularism stems from the polar opposites of Christian evangelism and Islamic extremism, one seeking to restore religious values to the public realm, the other engaged in terrorism to advance its interests. Mix these conflicting ingredients and the result is a contest of which no one can predict the outcome.

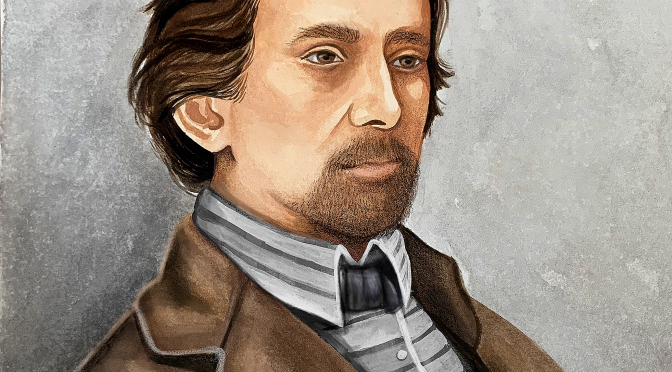

George Jacob Holyoake, a radical English social reformer and atheist, invented the word secularism in 1851, propagandised its message, and struggled to raise the moral standards and material conditions of his countrymen. Yet for some unknowable reason, Holyoake has virtually vanished from history, unheard of by the public. There is no mention of his name in one of the most eminent of books on secularism, Charles Taylor's A Secular Age.

In order to bring Holyoake the recognition he deserves, I have written his first modern biography, Inventing Secularism: the radical life of George Jacob Holyoake. It will be published in spring 2021 by McFarland & Co., USA.

George Jacob Holyoake was born in Birmingham in 1817 and died in Brighton in 1906. Notwithstanding his origins in the 19th century, Holyoake was a man for the modern age. His vision encompassed ideals of social justice that would become universally accepted nearly 200 years after he first expressed them. Through a long, controversial, and conflict-filled life, marked by as many mistakes as triumphs, he was in the vanguard of almost every struggle to improve the lives of ordinary people – public education, the co-operative movement, freedom of the press, trade unions, women's rights, and universal suffrage.

He was hailed after his death as "one of the men who fought for and won for Englishmen that freedom of speech which we take as a matter of course today". For a man largely neglected in popular history, he played a transformative role in the evolution of modern life and the rise of democratic rule in Britain and the west.

Holyoake came to the idea of secularism after enduring hardship, persecution, and imprisonment as a social missionary for capitalist turned reformer Robert Owen and his socialist utopian movement, the Society of Rational Religionists. After a Christian upbringing, George Holyoake fell into atheism with the imprisonment of a friend for blasphemy and his own arrest for a speech in which he declared he no longer believed in such a thing as a god. Convicted of blasphemy, Holyoake reflected on the conditions of English life during his six months in the Gloucester County Gaol. He came out convinced of the need for a new social order that would release the individual from the grasp of enforced religious doctrine.

Upwards of 100 countries now affirm support for secularism. The United States has functioned as a largely secular state despite a continuing presence of religiosity in its public life; the United Kingdom, secular in many respects, retains an established church with appointed bishops in its House of Lords, religious schools, and a monarch who is head of both the church and the state.

Canada, nominally secular, recognises "the supremacy of God" in its constitution and provides public funding for Roman Catholic schools. Quebec's bans on the wearing of hijabs by public sector workers in positions of authority may go too far, in the opinion of many. British-controlled India adopted secularism for its promise of harmony between Hindus and Muslims, a hope that has receded under the long-reigning Modi government.

Religious belief is in free fall everywhere in the west. People of no religion (the 'nones') account for 52% of the population of England and Wales, and one-quarter of the population of the United States and Canada. Only 12% of Britons are affiliated with the Church of England, down from 40% in 1983. There is strong support for the secularist tradition in France, and for secularist principles in the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Australia. China pays lip service to secularism but uses its atheist ethos to oversee its Christian citizenry and oppress its Muslim minority.

In contrast to these trends, secularism finds itself in a state of siege in many countries. Christian evangelists in the United States are pushing to have their religious ideas enacted into public policy in fields as diverse as health, education, foreign aid, and law. President Trump's attorney general has openly declared war on secularism and hundreds of millions of dollars of coronavirus aid have been transferred to churches, in violation of the US constitution. In Turkey, long the most secular Muslim country, the famed Hagia Sophia, a museum since 1935, was recently reestablished as a mosque. Three states that were once secular – Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan – have enshrined Islam as their official religion.

Meanwhile, Islamic fundamentalism uses the blunt force of terrorism to attack rival faiths and the infidel idea of secularism. Secular states must respond to the pressures of 21st century migrations and the accommodation of non-secular traditions.

George Holyoake looked beyond his own time, confident that "secularist principles involve for mankind a future". It would be a future of moral as well as material good, offering an infinite diversity of intellect with equality among humanity, and "all things – noble society, the treasures of art, and the riches of the world – to be had in common".

His was a vision of a secularism that rises above sectarian differences or economic rivalries, and places universal opportunity, and individual freedom, in the hands of all who inhabit our rich and beautiful – but endangered – planet Earth. It is not too late for us to fulfill his vision.

This is a lightly edited version of a piece which was originally posted on the Humanist Freedoms blog. It's reprinted here with kind permission.

Photo courtesy of Ray Argyle: Portrait of George Holyoake, by Sarah Watson.

Please join us for a free online event Inventing Secularism: The Radical Life of George Jacob Holyoake – book launch with Ray Argyle, Thursday 22 April 2021

While you're here

Our news and opinion content is an important part of our campaigns work. Many articles involve a lot of research by our campaigns team. If you value this output, please consider supporting us today.