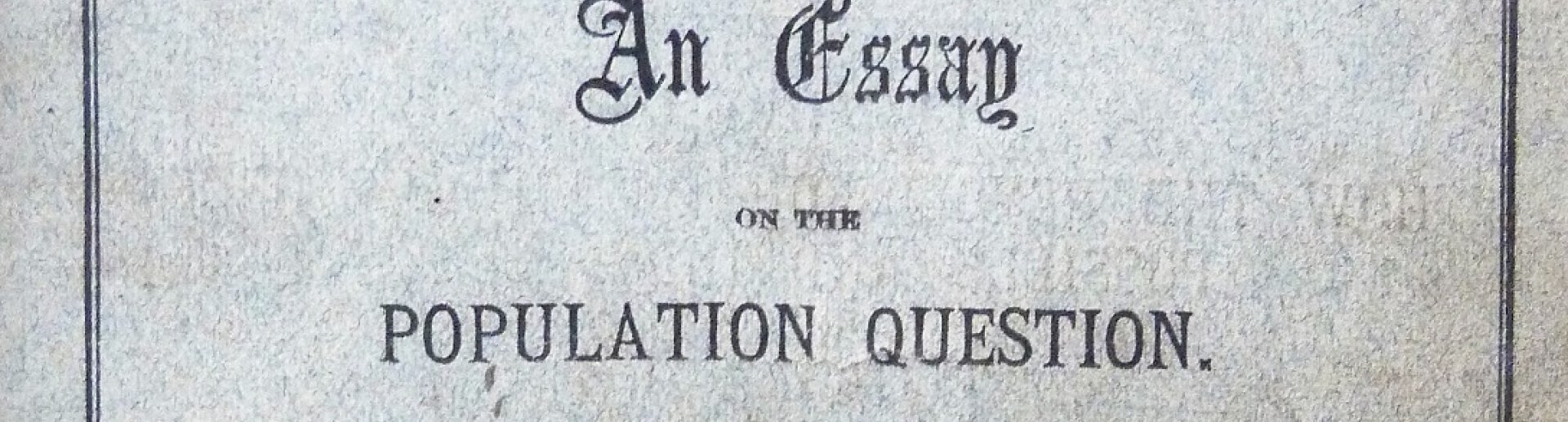

The Bradlaugh and Besant edition of Knowlton's 'Fruits of Philosophy'.

The Fruits of Philosophy was a relatively obscure publication which provided elementary (but not entirely accurate) contraceptive information. It was originally published by a New England doctor named Dr Charles Knowlton in 1832.

In 1834 James Watson brought out the first English edition. It achieved steady if unspectacular sales in the years that followed. In 1875 the plates were purchased by Charles Watts, who had helped Bradlaugh found the NSS. Watts became the new publisher.

The pamphlet was propelled into the public eye in 1876 when a Bristol bookseller, Henry Cook, was sentenced to two years' hard labour for selling it. To Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant's consternation, Watts – their close associate – agreed to the destruction of the printer's plates and his stock. Confronted with the prospect of a prison sentence, he argued that the pamphlet was not worth fighting over.

Bradlaugh and Besant responded by founding their own Freethought Publishing Company at 28 Stonecutter Street (near Fleet Street). This publishing works and radical booksellers was to become the NSS headquarters for the rest of the century. Bradlaugh and Besant republished the pamphlet, modified the text a little, and attempted to bring it up to date with medical footnotes by Dr George Drysdale. From the outset they were determined to test the law.

There was nothing in the pamphlet that was unknown to medical practitioners or which had not been published before. The issue was that it was being published at a price (sixpence) that made it available to ordinary working people.

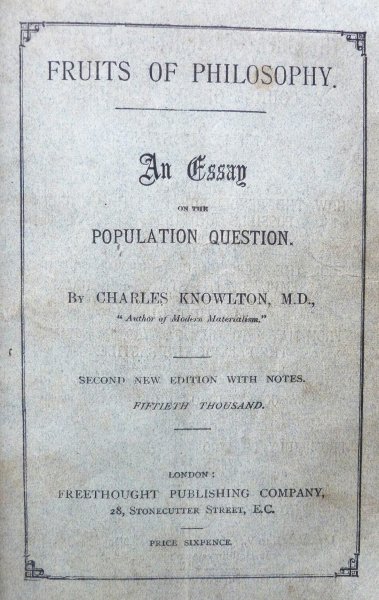

Annie Besant at the time of the Knowlton pamphlet trial

At 4 p.m. Saturday 24 March the new edition went on sale and 500 copies were sold in the first twenty minutes, including some to the police.

On Thursday 5 April 1877, Bradlaugh and Besant were arrested and charged for breaching the Obscene Publications Act 1857. They were committed to trial at the Old Bailey and the case was brought before the Queen's Bench on 18 June amidst great publicity. The case was tried by the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Alexander Cockburn. The Solicitor General, Sir Hardinge Giffard, led the prosecution. This highlighted the importance of the case.

Both Bradlaugh and Besant conducted their own defence; this was unusual in any event, but remarkable for a woman in the 1870's. The trial lasted four days before a divided jury returned a qualified guilty verdict. However, the story did not end there because Bradlaugh then managed to have the judgment set aside on a technicality concerning the wording of the original indictment.

Another veteran freethought bookseller was not so fortunate. Edward Truelove received a sentence of four months in prison and a fine of £50.

Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant had become household names. In the eyes of some they were notorious. To others they were heroes.

During the last 20 years of the 19th century the birth rate began to decline. The Fruits of Philosophy was replaced by more modern birth control pamphlets such as Annie Besant's own The Law of Population and Henry Allbutt's The Wife's Handbook. These were widely sold and distributed in their hundreds of thousands by booksellers and publishers associated with the NSS.

There had been a cost, because not all secularists had agreed with the stance taken by Bradlaugh and Besant. But by 1880 all that changed: secularists reunited behind Bradlaugh over his struggle to enter parliament.

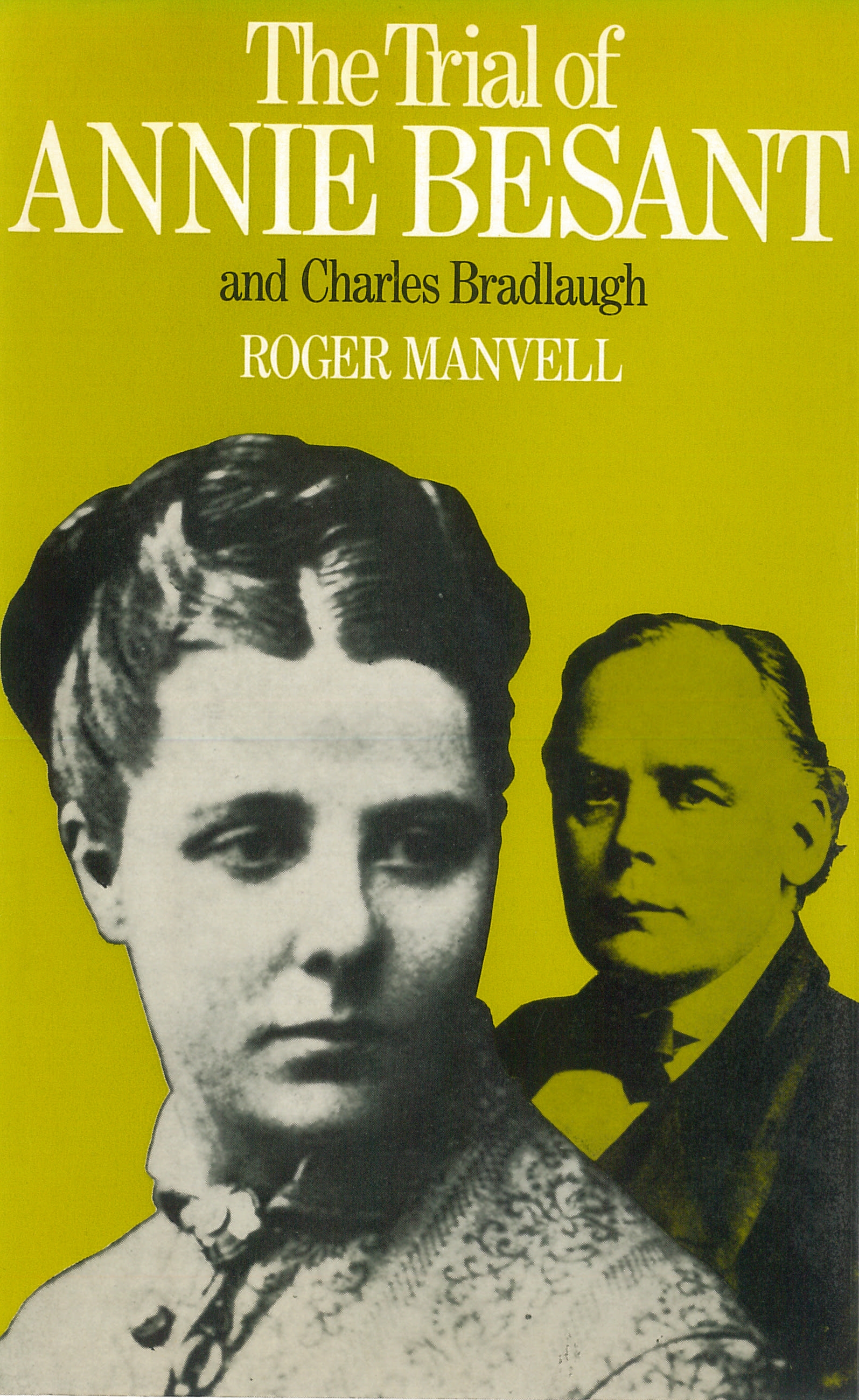

A book by Roger Manwell documented the trial of Besant and Bradlaugh