The BMA’s opportunity to rethink its position on assisted dying

Posted: Fri, 23rd Oct 2020 by Dr Antony Lempert

The British Medical Association's opposition to assisted dying is at odds with its members' views. There's now a chance for the BMA and parliamentarians to stand up to religious obstructionism, says Dr Antony Lempert.

On 8th October, the British Medical Association (BMA) published details of the largest ever survey of UK doctors on the subject of physician-assisted dying. The results of the survey paint a picture, as nuanced as it is, which is nevertheless starkly at odds with the BMA's long-term policy of absolute opposition to assisted dying (AD). That the survey happened at all was in spite of attempts by a minority of doctors to frustrate the process. What can no longer be hidden is that there is significant support within the medical profession for the legalisation of AD.

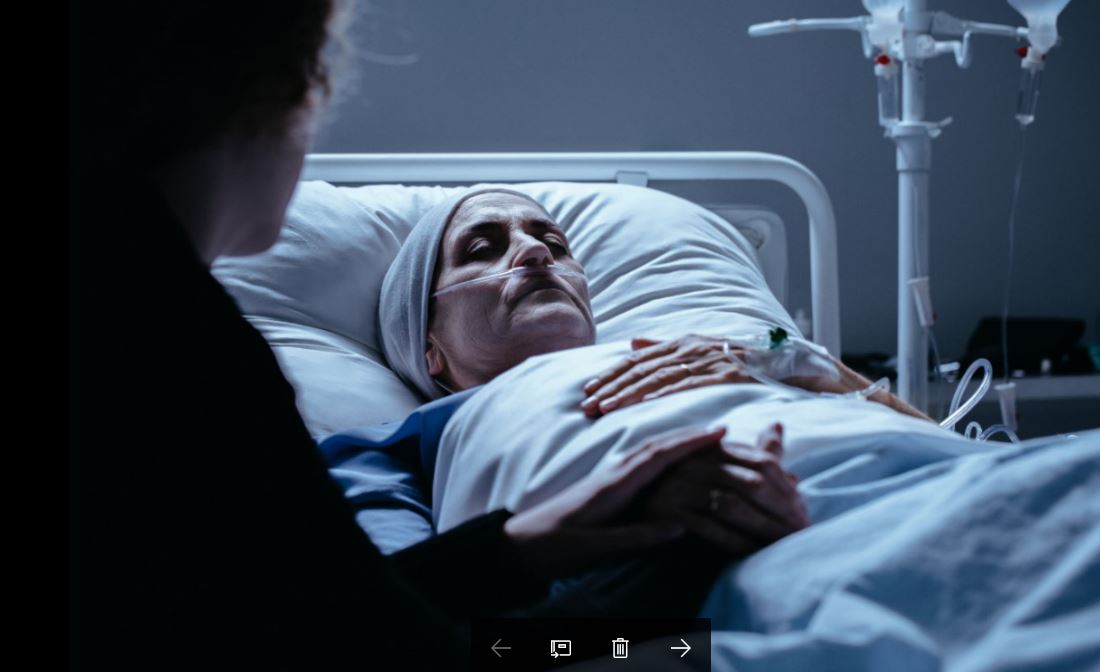

Current AD legislation dates from 1961. Although suicide itself was decriminalised, anyone found guilty of assisting someone else to take their own life is guilty of a crime. In 2012, the director of public prosecutions further clarified that doctors who assist patients to die would be at most risk of prosecution. Patients' options are thus restricted, leaving some in avoidable torment feeling desperate and abandoned; open, honest doctor-patient communication is hindered, with the risk of botched suicides and the additional risk of prosecution faced by relatives if they respect the patient's own wishes and help them to end their suffering.

The influence of medical professional bodies' historic opposition to AD cannot be understated. Opponents of AD, arguing in favour of the status quo, have long relied on claims that doctors oppose AD in order to bolster their arguments and to persuade parliamentarians to maintain opposition. Since the majority of BMA policy is decided by BMA representatives at its annual representatives meeting (ARM), this survey does not force the BMA's hand. Nor will it necessarily convince politicians that the time is now right to listen to the overwhelming majority of the public who consistently support properly-regulated, legalised AD for people suffering unbearably and with no realistic prospect of relief. It does, though, burst the bubble of those who have fought so hard to prevent the wide variety of doctors' views from seeing the light of day.

In February this year, almost 30,000 BMA members, approximately one fifth of the membership, responded to the survey questions posed by the independent research organisation, Kantar. The questions were subdivided into doctors' personal opinions and their views as to the position they would like to be adopted by the BMA, the main UK trade union and professional body for doctors. Comments were also included in the summary if at least five per cent of respondents made the same point, allowing for a greater understanding of the reasoning behind doctors' decisions.

When asked for their views regarding a change in the law that would "permit doctors to prescribe drugs for eligible patients to self-administer to end their own life" only one third of respondents expressed support for the BMA's current position of active opposition. This leaves twice as many doctors unrepresented by the BMA's existing oppositional stance. Forty per cent of respondents thought the BMA should actively support AD legislative change with 21% in favour of BMA neutrality and six per cent undecided.

Doctors' personal views on the same question showed that half were in favour of legalising AD, 39% were opposed with 11% undecided. It is not surprising that doctors' opinions are more conservative than public opinion in this matter. Should the law change and a regulatory process be adopted in any way similar to the increasing number of other jurisdictions where AD has been legalised, then some doctors would be personally involved in the process; currently a UK doctor whose patient wishes to discuss AD must instead simply advise them that it is illegal.

An overwhelming majority (93%) of survey respondents felt that individual doctors should be guaranteed the right to exercise a conscientious objection to participation in AD should it be legalised. Nevertheless, with 36% of doctors expressing personal willingness to prescribe and 26% willing to administer life-ending drugs, it is likely that those patients who express a wish to consider AD to end their suffering would be able to find a supportive doctor.

No-one should claim from these statistics that there is a clear mandate of UK doctors either for or against legalisation of assisted dying. This is precisely why so many of us who personally support legalising AD would still prefer our professional bodies to adopt a neutral position. Neutrality recognises that this is primarily a societal decision, and enables medical bodies to advise government on the medical implications of all options rather than offering a partisan viewpoint.

The last substantive ARM debate on AD took place in 2016, reaffirming policy made in 2012. In response to the 2012 motion calling for neutrality, that I had written and submitted via my local BMA division, the then BMA chair Dr Hamish Meldrum opined that a neutral position would leave the BMA unable to contribute to the debate. He recommended to representatives that they vote against neutrality, which sufficient numbers duly did to defeat the motion.

It was curious therefore that, in 2014, in response to proposals in Rob Marris MP's assisted dying bill, the BMA commented: "For reasons of inconsistency with BMA policy it would be inappropriate to engage with the detailed proposals in the Assisted Dying Bill." In other words, far from neutrality leaving the BMA unable to engage with parliamentarians, it was precisely the rigid binary opposition that prevented MPs from hearing from the medical profession a balanced view of the risks, benefits, practical problems and solutions that might pertain to the introduction of assisted dying legislation.

Whatever the motivation for the chair's recommendation to vote against neutrality, religious influence has certainly played a large part in the AD debate, wherever it takes place. The evening prior to the 2012 ARM debate on AD, the newly installed BMA president Baroness Hollins used the privileged platform of her inauguration speech to BMA representatives to influence the next day's debate by focusing on her opposition to AD. This was particularly disappointing considering what she had said just one month previously, when she had featured on Radio 4's Desert Island Discs (start: 23:30). Asked explicitly about the relationship between her personal religious (Catholic) beliefs opposing AD and her then role as president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in drawing up AD policy, she had replied: "As president of a secular organisation I wouldn't let my particular religious beliefs interfere with that." She had additionally gone on to comment how some might find that difficult to believe.

Recently, other medical colleges have been undertaking similar exercises to understand their members' views with regard to AD. Earlier this year, the Royal College of GPs (RCGP) released limited details of its 2019 survey of members' views about AD. Here too, in a college positionally opposed to AD, only a minority of GP respondents concurred. The subsequent RCGP decision to maintain its active opposition despite these results has resulted in a legal challenge (still ongoing) against the RCGP from two senior members. A few months previously, the Royal College of Physicians' (RCP) survey on AD had also shown that there was no clear mandate from its members in either direction. The RCP took the rational step of switching from opposition to neutrality in order to better represent all its members' views.

At last year's BMA ARM, held in Belfast in June 2019, where I was honoured to propose the successful motion calling for the BMA to support the decriminalisation of abortion across the UK - another bête noire of the pro-life brigade - AD was on the agenda again. The 2019 AD motion was to debate whether or not to survey all members' views about moving the BMA to a position of neutrality. Both debates were particularly noticeable for the dearth of religious argumentation used by representatives opposed to the motions. Anyone attending their first ARM might have been forgiven for taking at face value the concerns of those who opposed both motions.

Two or three familiar faces from previous years' debates who had spoken strongly against AD itself, now turned their gaze to the process (start: 55:12). We heard that a poll would be too expensive, and AD wasn't a 'binary' issue which could easily be put to the BMA membership; the irony that existing BMA policy is unashamedly binary was perhaps lost on the speaker? In the event, the vote to survey all members was passed by a small majority, which precipitated this year's survey.

The current pattern of avoidance of the use of religious arguments by opponents of AD is neither incidental nor coincidental. The 2006 Lords debate of the late Lord Joffe's assisted dying bill was peppered with the noble lords' religious objections to AD. Nine years later, and religion featured sparingly during the 2015 debates about the Marris AD bill. Over the past few years, there is evidence that religious people have been advised to try to win over the increasingly-secularised majority with secular-sounding arguments and to avoid using religious terminology. They have been tutored to reframe the AD debate in terms of plausible sounding arguments such as the focus on patient vulnerability, slippery slopes, the importance of alleviating pain, the risks to society and to the medical profession.

The problem is not that these important arguments do not need to be discussed - they do - it is that most of the assertions made around these arguments by pro-life proponents are fear-mongering, and often grossly distorted to fit the argument. For example, patient vulnerability is often cited as a prime reason why AD should remain illegal. Whereas supporters of properly-regulated AD legislation recognise that vulnerable people who request AD do need strict safeguards, opponents regularly fail to acknowledge the evident fact that many people are already extremely vulnerable under the current legislation. They do not speak of the minority of patients whose suffering simply cannot be relieved even with gold standard palliative care, instead offering unhelpful, arrogantly presumptive platitudes about their needing more love or better treatment which would somehow magic away their suffering.

Most people who contemplate AD are in unbearable torment and are therefore inherently vulnerable. Equally, without AD legislation, with no legal avenue to approach, the only time that relatives may be questioned as to whether the person they may have (illegally) assisted to die is after the person is dead when it is too late to offer a possible remedy and the deceased's views can no longer be known with certainty. Strictly regulated legalised AD would reduce the vulnerability both of the suffering patient and of the rare patient whose unscrupulous relatives might later try to claim that their death was voluntary rather than murder.

Nobody is arguing that anyone should disrespect or disregard the personal views of patients or doctors who oppose AD; quite the opposite. In contrast, however, the views of many suffering people who are in favour of AD for sound reasons, and who do not agree with the scare-mongering of the pro-life brigade, are being disrespected and frustrated by people not content with personal disagreement, but who are actively engaged in enforcing their (religious) world-view.

In recent times, we have heard that some religious authorities believe they are acting 'in the greater good' by pushing religious ideology even where it is not wanted. Some religious people genuinely believe that the ends justify the means in order to prevent what they regard as the evil of assisted dying.

Similar 'greater good' arguments were used by the Church of England and by the Catholic Church in the recently exposed long-term practice of covering up child abuse. The justification later offered was that reporting of clerical child abuse might have caused people to lose faith in the church's assumed moral authority. Pushing religious ideology where it is not wanted, whether by fair means or foul, is unacceptable, denies patients their personal autonomy, and leads to physical and moral harm.

The BMA had initially intended to publish the AD survey results in time for them to be debated at the June 2020 ARM. In the event, the extraordinary circumstances of the Covid-19 pandemic caused the postponement of the usual four-day ARM. Many of us still wanted the results to be published and a debate to go ahead so any change in BMA policy would not have to wait another year. Instead, the ARM was held as a one-day virtual meeting in September with a decision to withhold the survey results until after the ARM. Most likely, therefore, AD will be debated at the ARM in June 2021.

Given the views of the BMA's members, adopting a neutral position would be eminently reasonable. And should it do so, this would be a golden opportunity for the BMA to demonstrate professional leadership and to inform the parliamentary debate around assisted dying with principles based on medical evidence, patient autonomy and medical ethics, rather than religious dogma.

Dr Lempert is a BMA member and has been a representative since 2009, though he writes here in a personal capacity.

While you're here

Our news and opinion content is an important part of our campaigns work. Many articles involve a lot of research by our campaigns team. If you value this output, please consider supporting us today.