Photograph of the Great Chartist Meeting on Kennington Common, London in 1848 (public domain) Image By William Edward Kilburn.

Secularists and freethinkers (as they were generally called at this time) were at the forefront of many early nineteenth century reform and protest movements.

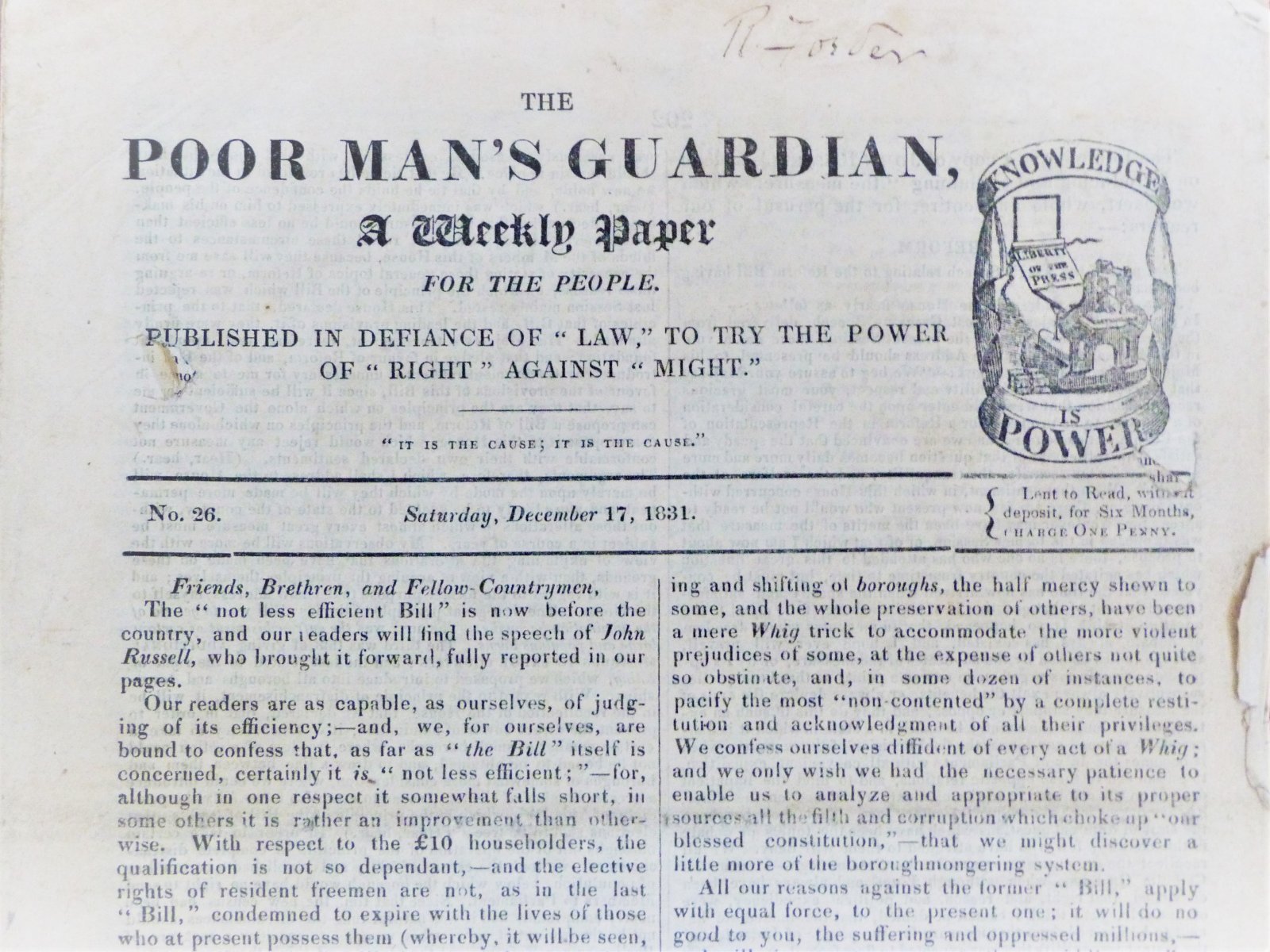

The Stamp Acts

In the years following the French Revolution British governments took highly repressive measures they considered necessary to curb the danger of revolution at home. Among the measures introduced were the Stamp Acts which imposed a punitive stamp duty on cheap, radical newspapers in an attempt to price them beyond the means of ordinary people.

Secularist publishers such as Henry Hetherington (1792-1849) with his Poor Man's Guardian and James Watson (1799-1874) with his Working Man's Friend defied the law and attempted a variety of ruses to get around it. In Hetherington's case this included the pretence that his newspaper was being loaned for the princely price of one penny, not sold. They were unsuccessful in that they both served prison sentences.

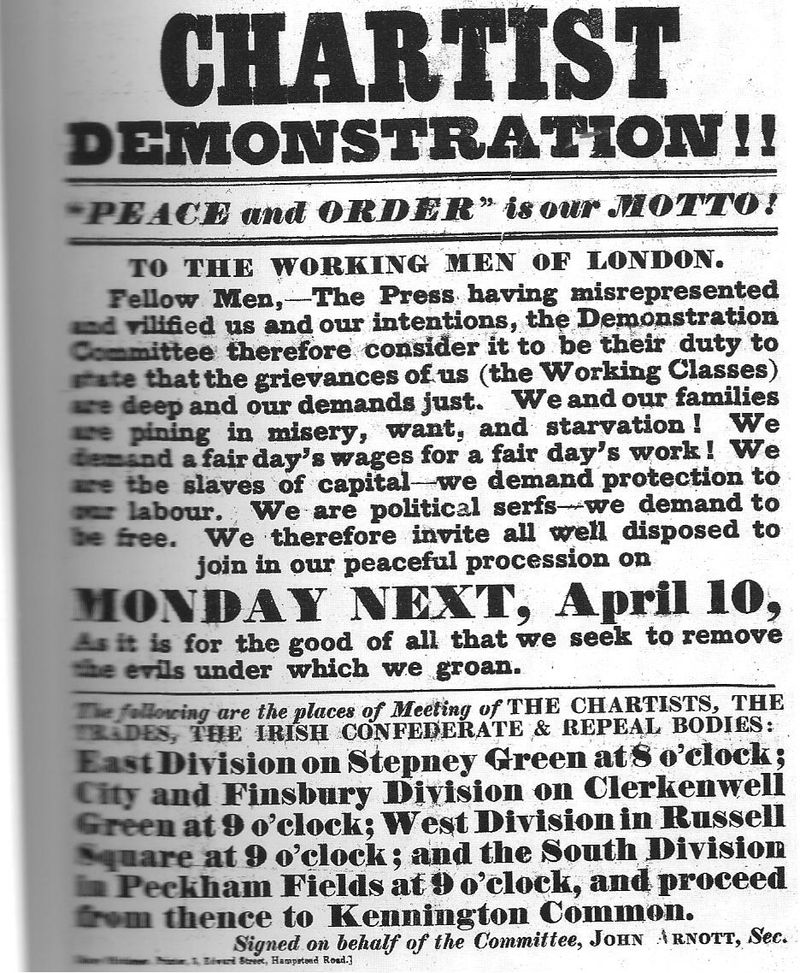

Chartism

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform that existed from 1838. Secularists, such as Henry Hetherington and James Watson and other followers of Thomas Paine, dominated its leadership. They were often particularly incensed by the opposition of the established church to their demands. To freethinkers the Church of England was nothing more than a prop to those who wielded political power which they had no intention of surrendering.

This led to many Christians who supported Chartism to oppose the Church of England, its leadership or establishment. The bishops', who then as now had seats in the House of Lords, were consistent in their opposition to reform.

Chartism took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement. Support was at its highest in 1839, 1842, and 1848, when petitions signed by millions of working people were presented to the House of Commons. The strategy employed was to use the scale of support which these petitions and the accompanying mass meetings demonstrated to put pressure on politicians. Chartism thus relied primarily on peaceful and constitutional methods to secure its aims.

The Chartists demands can be summarised as follows.

- Universal suffrage (the vote for all – later modified to universal manhood suffrage on the insistence of more cautious campaigners).

- An end to property qualifications for voters and candidates.

- Annual parliaments (general elections each year).

- Equal representation (each constituency to be roughly the same size).

- Payments of members (so ordinary people could become MPs).

- Vote by ballot (secret voting, on paper).

In their own era, the Chartists failed and the movement suffered a serious blow in 1848 when a mass meeting held on Kennington Common was prevented from crossing the Thames and marching on Parliament. When examined, the petition itself was found to be far smaller than its organisers had claimed and carried many false names.

However, secularist aspirations for reform remained. In the 1860s electoral reform was again a key issue with the Reform League being established in 1865. Charles Bradlaugh was one of the League's founders and was ultimately to benefit from the extension of the franchise which it helped bring about when he was elected to Parliament in 1880.

See also: Peterloo's heroes represented the finest traditions of secular democracy.

Unknown. Signed by John Arnott (1799 - 1868) - Scanned from Rodney Mace, British Trade Union Posters: An Illustrated History - Public Domain