By 1880 Bradlaugh had emerged as undisputed leader of the secularist cause and the leading radical of his time. He was famous for his oratory and could attract audiences of thousands. His books and pamphlets on a variety of radical themes commanded huge sales and he was known nationally for his campaign to publish Charles Knowlton's birth control pamphlet.

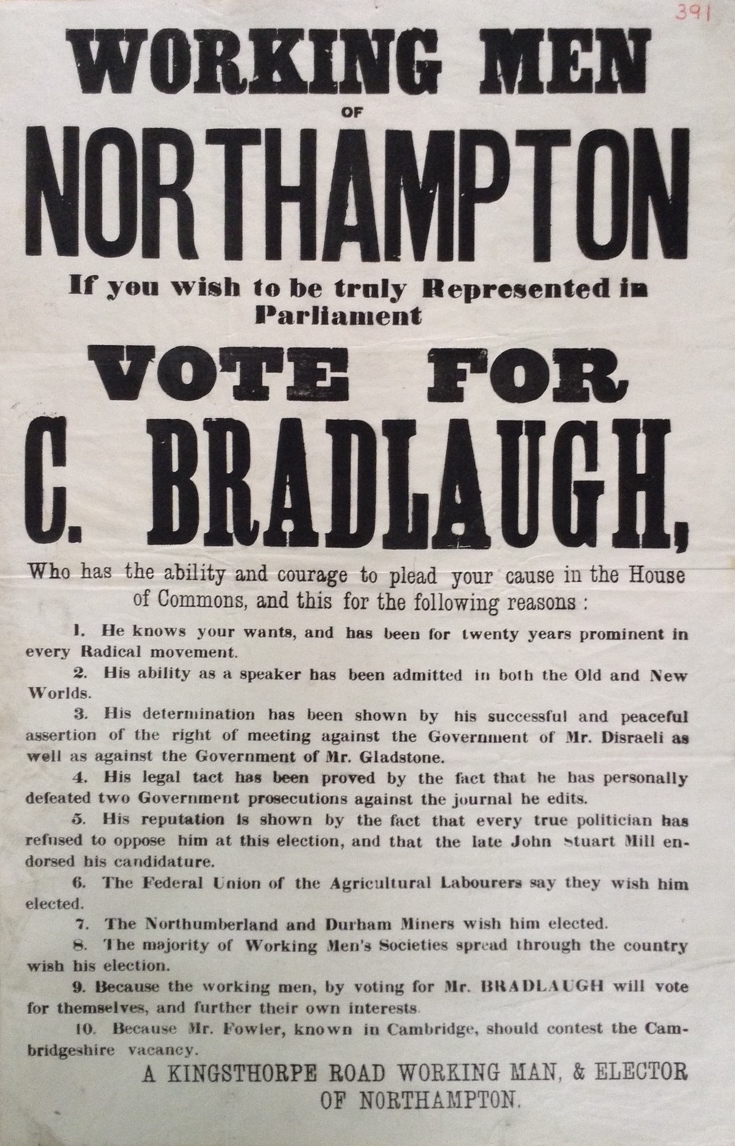

As a constitutionalist Bradlaugh was convinced that the way to change society was through parliament. In 1868 he first stood for election for the Northampton constituency which was then a single constituency electing two MPs. He chose Northampton, a town of shoemakers, for the radical traditions associated with that trade.

In 1880 Bradlaugh was adopted as a Liberal candidate alongside Henry Labouchere. The timing was fortunate. In 1880 the Liberals achieved their biggest general election victory of all time and William Gladstone formed his second ministry. Bradlaugh and Henry Labouchere were returned as Northampton's MPs.

Since 1870 non-believers had had the legal right to make a secular affirmation in the English and Welsh courts. Bradlaugh believed this qualified him to affirm when taking his seat in the House of Commons and informed the Speaker of his intention. As an atheist and republican he preferred not to take an oath of allegiance to God and the Queen – although he would do so if it meant he could take his seat, the words of the oath being meaningless to him.

The House of Commons refused to allow his affirmation, so Bradlaugh applied to take the oath. Again he was refused. Bradlaugh was effectively barred from taking his hard-won seat. To Bradlaugh and many others this was a grievous breach of democratic rights. He was being refused his seat because of what others thought of his opinions and parliament was ignoring the wishes of his constituents.

At one time, and to further complicate matters, the House of Commons took the perverse position of allowing Bradlaugh to affirm, subject to penalty in the courts. There followed legal actions which sought to bankrupt him and disqualify him as an MP. Bradlaugh acted for himself, taking on the finest lawyers in the country, eventually emerging victorious. However, this was at a huge personal cost.

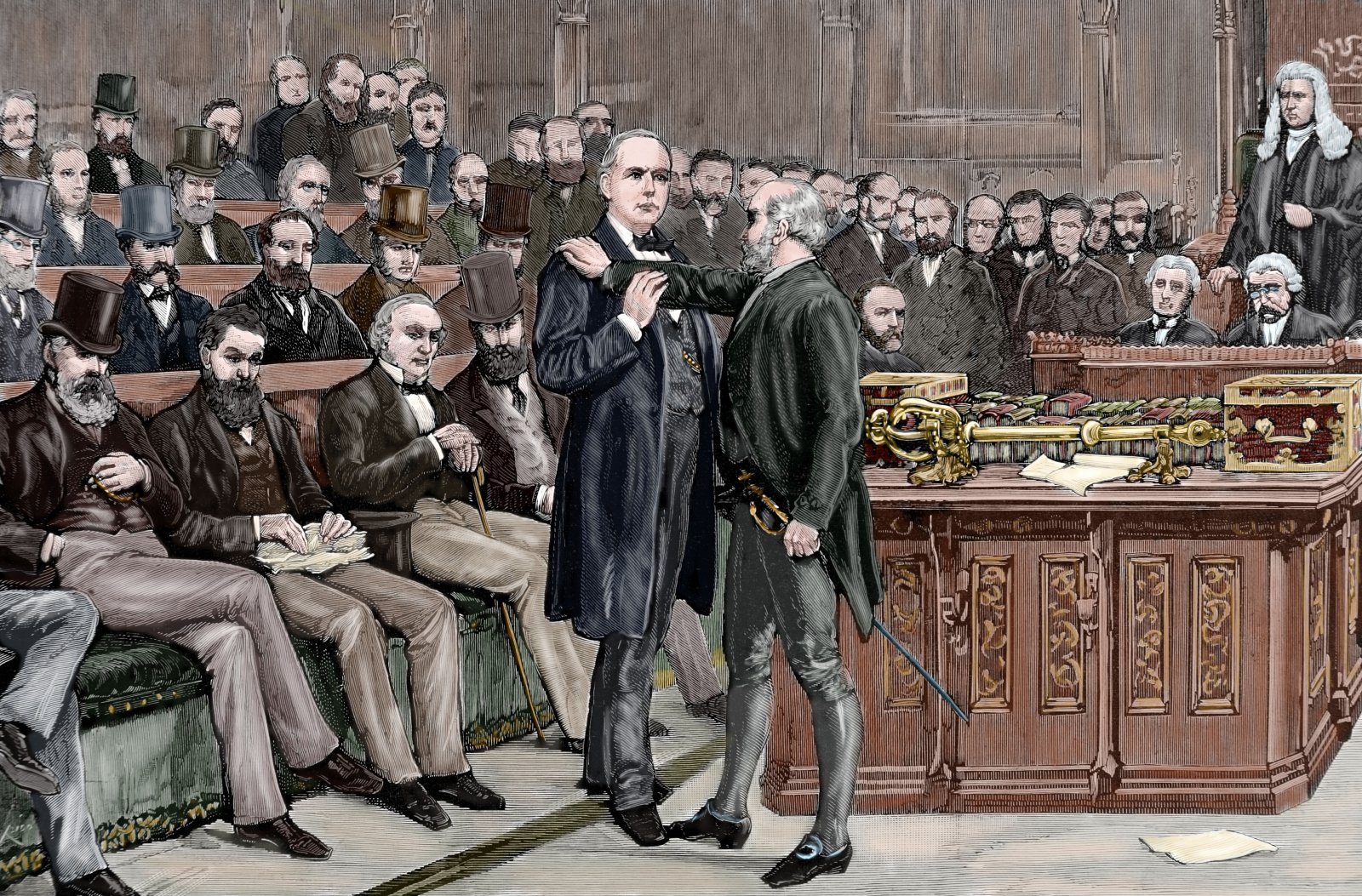

In the years that followed he continued his fight to take the oath. Four times in the early 1880s his constituents re-elected him; four times he made passionate speeches at the Bar of the House. The Bar marked the boundary of the House – he was allowed to speak to MPs there, because he was not strictly within the House of Commons.

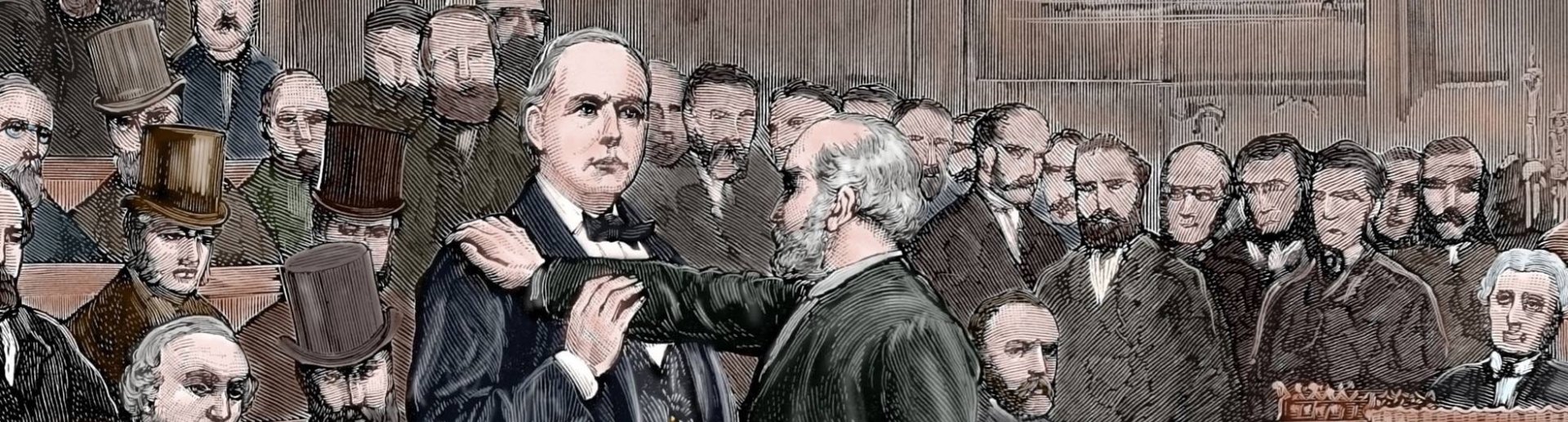

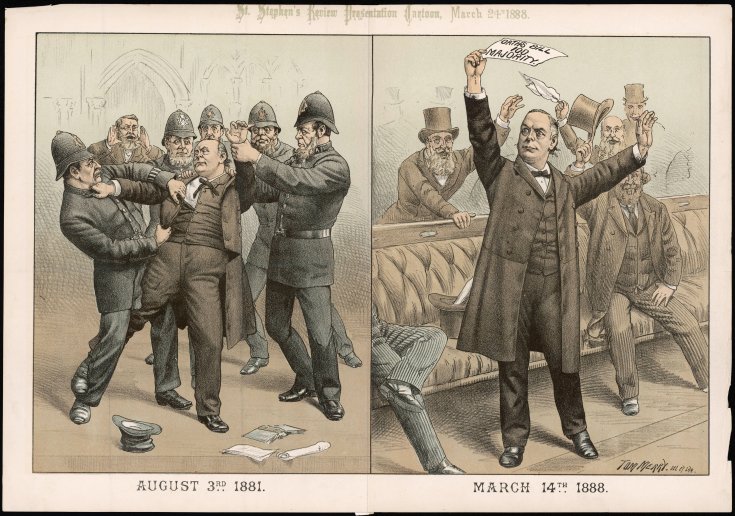

Charles Bradlaugh at the Bar of the House of Commons

On one occasion he refused to withdraw from the Chamber when commanded to do so by the Speaker. He was taken into custody and confined to the prison room of the Clock Tower before being released the next day. On another, Bradlaugh came to the House of Commons at the head of a vast crowd demanding that he be allowed to take his rightful place. He was physically ejected by the police and parliamentary officials, suffering injuries in the process. Despite this provocation he used his power over the crowd to urge them to disperse peacefully.

Eventually the impasse was resolved after the General Election of 1885 when a new Speaker took the dramatic decision of allowing Bradlaugh to take the oath, which he did on 13 January 1886. Almost six years after being first elected Bradlaugh had won, but at immense personal financial and physical cost.

His victory was further underlined by Parliament passing an Oaths Act (1888) which extended the civil rights of freethinkers and secured the their right to affirm when taking their seat in parliament. Many MPs take advantage of this today.

Bradlaugh triumphs with the passing of the Oaths Act in 1888

In the years that remained to him, Bradlaugh championed much reformist legislation and received the accolade of becoming known as The Member for India for championing Indian people's interests. Charles Bradlaugh was always the underdog's friend.

Perhaps the greatest recognition of his victory and achievement occurred as he lay on his deathbed. On 27 January 1891 the House of Commons resolved that its original decision preventing him from taking the oath "be expunged from the journals of the House, as being subversive of the rights of the whole body of electors of this Kingdom".

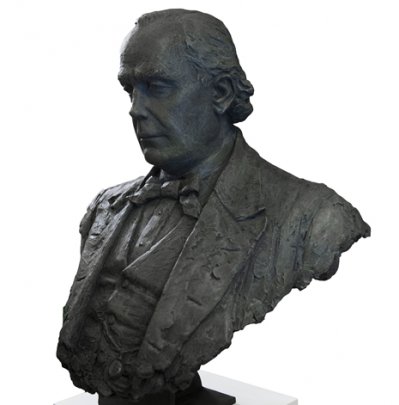

Charles Bradlaugh died from kidney disease on 30 January 1891 aged 57 without knowing of the resolution. Today his achievements are commemorated by his statue in Abingdon Square, Northampton and by his grave in Brookwood Cemetery. Perhaps most poignantly, in 2016 Suzie Zamit's portrait bust was unveiled in the Palace of Westminster during the NSS's 150th year. Today it is displayed alongside other celebrated reformers and radicals. Charles Bradlaugh's heroism and self-sacrifice has not been forgotten. His example remains an inspiration to a new generation.

The portrait bust of Charles Bradlaugh as displayed in the Palace of Westminster. The bust was donated by the National Secular Society in 2016 to mark the Society's 150th anniversary.