Secular Education Forum

The Secular Education Forum (SEF) provides expert and professional advice and opinion to the National Secular Society (NSS) on issues related to education and provides a forum for anyone with expertise in the intersection of education and secularism.

The SEF's main objective is to advocate the value of secularism/religious neutrality as a professional standard in education. The SEF welcomes supporters of all faiths and none. It provides expert support for the NSS working towards a secular education system free from religious privilege, proselytization, partisanship or discrimination.

Want to get involved?

Sign upJoin our mailing list to apply to join the forum. You'll be kept up to date with news, meetups and opportunities to contribute or volunteer.

Membership of the Secular Education Forum is intended for education professionals (including current, former and trainee professionals) and those with a particular expertise in the intersection of secularism and education. All requests to join will be considered after signing up to the mailing list.

Education blogs and commentary

A selection of blogs and comment pieces on education and secularism. For education news from the NSS, please click here.

Talk of a public appetite for religion is wishful thinking

Posted: Thu, 22nd Sep 2022

The established church's proclivity to insert itself into the secular realm should not go unchallenged, argues Stephen Evans.

Events around the Queen's death have led several commentators to become excited about what they see as enthusiasm for Christianity in Britain.

Under the headline "Britain is yearning for traditional Christianity", Telegraph columnist Madeline Grant remarked that "this traditional funeral – an unambiguous statement of Anglican faith – drew one of the biggest audiences in TV history." She opined that Queen Elizabeth's funeral "proved" the public doesn't want a dumbed down version of the Church.

Meanwhile, religion commentator Catherine Pepinster likened the queue to a "pilgrimage", remarking that people "crossing themselves, bowing and making other religious gestures before the coffin" (not that bowing before a coffin is a religious gesture) means "Britain is not as secular as we might assume".

In a Religion Media Centre briefing, the public's response was described as "religious". Professor Rev Ian Bradley, Emeritus Professor of Cultural and Spiritual History at the University of St Andrews, said "events of the last week have exposed and unleashed a latent spirituality".

All of this will be no doubt be utilised to promote more religion in public life.

But I'm not convinced people tuning in for the Queen's funeral reveals a hidden and untapped yearning for Christianity. It did attract a massive audience (at 29 million only slightly less that the Euro 2020 football finals). Given the national shut-down and the only other thing on television being The Emoji Movie, this isn't surprising.

As the Queen was a practising Christian and 'Defender of the Faith', her funeral was inevitably a religious event. But it was also perhaps the grandest state occasion in living memory. A national event to bid farewell to the longest-reigning and much-admired British monarch. My guess is people were watching for a variety of reasons. Many may have 'tuned out' of the religious bits.

It's also important to note that ritualism should not be mistaken for religiosity. It's clear that most people's tributes to the Queen, while full of symbolism and tradition, were secular in nature - noticeably so, in fact.

As Peter Stanford, a former editor of the Catholic Herald noted in The Guardian: "The need for ritual to mark a death has been with us since before religion came along. It is hard-wired into the human psyche to yearn for something more when a life comes to an end, whether for the person who has left us, or for ourselves. The genius of religions – consciously or not – has been to develop whole theologies and funeral rituals around that urge."

So, is there an appetite for more Christianity in public life, or there is a lot of wishful thinking going on? My money's on the latter.

The reality is attendance at Anglican services has been declining since the mid-19th century. The latest available Church of England data shows that average Sunday attendance is around 600,000 adults, or fewer than 1% of the population. A third of those attending church are aged 70 or over.

Figures from the 2018 British Social Attitudes survey showed that 52% of the UK public said they did not belong to any religion, while only 38% identified as Christian. We're likely to see the drift away from Christianity continue when the national census figures are published later this year.

The entanglement between religion and monarchy means the Queen's death has provided a significant national platform for the Church of England. But its message is unlikely to resonate.

Earlier this year, the Archbishop of Canterbury reaffirmed a 1998 declaration asserting that gay sex is a sin, and that same-sex marriage is illegitimate. Meanwhile, a soon to be concluded Independent Inquiry into Child Sex Abuse has found the Church of England has failed abuse survivors and victims by defending alleged perpetrators instead of protecting children and young people from sexual predators.

Is it any wonder that surveys show as few as one percent of 18- to 24-year-olds now identify as Anglican?

The Church's lavish spending on evangelism (£248 million was spent between 2017 and 2020 as part of the church's "renewal and reform" programme to attract new worshippers) is looking like money down the drain.

With pews emptying the Church is increasingly keen to insert itself into public life. Last week, the Anglican Dioceses of London and Southwark dispatched chaplains to 'the queue', to offer pastoral support, introduce themselves, have conversations, and, "only if requested, pray with people." Thousands of Great North Run participants were kept waiting at the start line while an Anglican priest read a prayer urging them to "run together… through Jesus Christ our Lord."

Schools are already a key part of its evangelism via faith schools and mandatory worship, but the CofE is now seeking to gain a foothold in further education colleges to try and "build a younger and more diverse church". The Church is also hoping, with support from religious MPs, to play a much greater role in delivering healthcare and other public services.

Most of the above is inappropriate. It's legitimised by the Church of England being the established church. But the concept of national church is divorced from reality and modernity. The Church of England likes to see itself as a church for all. But Britain is too diverse to sustain such a vision. Citizens and communities can coalesce around many things. But Christianity is not one of them.

For the most part, the British public has put up with the Church's encroachment. But the Church's ability to insert itself into the secular realm and impose itself upon a largely indifferent population should not go unchallenged. It should of course be free to compete in the marketplace of ideas, but on terms of equality, not privilege. Freedom of religion should always be balanced against freedom from religion. Secular spaces should be protected.

Image: The queue for Queen Elizabeth's lying-in-state. Frank Carman, CC BY 2.0

Blasphemy laws, not books, belong on the bonfire

Posted: Wed, 21st Sep 2022

During Banned Books Week, Helen Nicholls examines the impact of blasphemy laws on those who write about religion – both in the past and today.

In the Middle Ages, it was not only books that were burnt but also authors and publishers. Anyone connected with a heretical or blasphemous work could potentially be burned at the stake.

In 1524 William Tyndale was forced to flee Britain for the 'crime' of translating the Bible into English. He was captured in Belgium and was strangled and burnt at the stake in 1536. His work could not be suppressed and was a major influence on later authorised Bibles, including the King James Bible.

As Britain became more liberal, the penalties for blasphemy became less severe, although fines and prison sentences could still be ruinous for those targeted. The last person to be imprisoned for blasphemy in Britain was John William Gott in 1922. His health was so badly affected that he died later that year.

Blasphemy laws were repealed in England and Wales in 2008 and in Scotland in 2021. They remain in force in Northern Ireland. But the existence of blasphemy laws anywhere can have a devastating impact on freedom of expression globally.

In 1989 Ayatollah Khomeini, the supreme leader of Iran, issued a fatwa that invited Muslims worldwide to kill the author Salman Rushdie and anyone involved with his book The Satanic Verses. Rushdie went into hiding for many years. In 1991 Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses, was found murdered at his university. Others involved with the production and sale of the book faced violence. Rushdie himself was stabbed onstage at an event in New York in August but thankfully survived.

One consequence of the fatwa was that The Satanic Verses has been far more widely read than it otherwise would have been. However, the fatwa nevertheless had a chilling effect on free speech as few writers or publishers would be prepared to risk suffering the same fate as Igarashi or Rushdie.

This was demonstrated in 2008 when The Jewel of Medina, a historical novel about Aisha, the wife of the Islamic prophet Mohammed, was dropped by its publisher due to fears that the book would be considered inflammatory. Martin Rynja, founder of Gibson Square publishers, announced his intention to publish it but changed his mind after his home was firebombed. The book was never published in the UK although the American edition is available here.

In recent years, there have been further attacks on those perceived to have insulted Islam. The most notable is the attack on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015 following its publications of cartoons of Mohammed. In 2020, teacher Samuel Paty was murdered in France for showing his high school class a Charlie Hebdo cartoon of Mohammed during a discussion on free expression. The following year, a UK teacher was forced into hiding after doing the same thing.

In the UK, no-one fears being killed by the state for blasphemy, but many fear being murdered if they are accused of insulting Islam. This de facto blasphemy law is perhaps harder to counter than a judicial one as there is no due process or mechanism for repeal. However, we can start by challenging those who claim that violence is an acceptable response to a novel or cartoon and support those who find themselves targeted by violent extremists. Otherwise, we risk having a right to free speech that exists in law but not in fact.

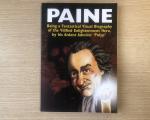

An exciting and unique introduction to the life of Thomas Paine

Posted: Thu, 1st Sep 2022

Paul 'Polyp' Fitzgerald's Paine: A fantastical visual biography is a new graphic novel on the life of Thomas Paine, a key figure in the history of secularism. Helen Nicholls explores how the book's unique approach helps keep Paine's story – and legacy – alive.

"He who dares not offend cannot be honest", wrote Thomas Paine in response to a critic. Paine's determination to speak his mind had serious consequences. In 1792, the British Attorney General prosecuted Paine for seditious libel for his book, The Rights of Man, which argued for a constitution based on democracy and human rights. Paine avoided imprisonment by escaping to France but his booksellers and publishers each received a sentence of three years' imprisonment. Paine was burned in effigy throughout England. He declared that the government had "honoured [him] with a thousand martyrdoms".

Paine's advocacy of freedom of expression and human rights is just as relevant today: religious fundamentalism continues to oppress and subjugate individuals, communities and societies around the world. Yet the life of Paine is not well known outside academic circles.

However, a new "visual biography" of Paine by cartoonist Paul Fitzgerald, also known as "Polyp", seeks to remedy this by telling his story in graphic novel format. Polyp said he produced Paine: A fantastical visual biography "as a way of paying homage to the world's least known revolutionary freethinking hero, and hopefully rescuing him from oblivion".

While Paine was a deist, believing in non-interventionist creator, his legacy has been largely preserved by atheists and secularists. In keeping with this tradition, the National Secular Society was a contributor to Polyp's crowdfunder to produce Paine's biography.

The book is narrated entirely through extracts from historical sources. Many are quotes from Paine's own writings. The rest come from his contemporaries, both supporters and detractors. It is beautifully illustrated and gives a vivid portrayal of its settings.

Most panels faithfully depict Paine's era - but with an irreverent streak. Paine is portrayed in one panel as Mr Spock, while another places him on the cover of Charlie Hebdo, reminding the reader that the struggle for the freedom to criticise religion persists to the present.

Paine would not have called himself a secularist as the word did not exist in his lifetime. However, he espoused the principles that form the basis of secularist thought. His greatest skill was his ability to communicate his ideas to the general public. But he was a victim of his own success as the popularity of his ideas and the threat they posed to the political and religious establishment meant that he was widely hated in his lifetime. The graphic novel brings this struggle to life, showing Paine as a brilliant but obstinate man who suffered personally for his work.

The book ends on an optimistic note, with quotations from admirers ranging from Abraham Lincoln to Christopher Hitchens. Polyp also includes quotations from G.J. Holyoake, who coined the term "secularist", and former National Secular Society President G.W. Foote, who said of Paine: "The keenness of his intellect was matched by the brilliancy of his imagination. His name stands for mental freedom and moral courage".

Paine: A fantastical visual biography is an excellent introduction to Paine for anyone interested in the history of secularist thought in an entertaining and accessible format.

Paine: A fantastical visual biography is available on Polyp's website here.

Watch NSS council member and historian Bob Forder tell Paine's story:

The Ayatollah will not have the last word

Posted: Tue, 16th Aug 2022

Salman Rushdie's battle is the battle of all of us who stand on the right side of history, says Pragna Patel.

The television images of the ferocious knife attack on Salman Rushdie on Friday 12 August 2022 have left me - like many others - in a state of shock and horror. It seems incomprehensible that decades after the fatwa pronounced by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, Rushdie has been attacked by a 24-year-old man who wasn't even born when The Satanic Verses was published. Fortunately, it appears that Rushdie will survive and, with him, our hope for humanity's freedom and progress.

For me, this attack on Rushdie is a particularly sobering moment. Like the fatwa in the first instance, it marks another milestone in my political journey as a black feminist, a journey divided into two distinct periods: Pre-Rushdie and post-Rushdie.

The pre-Rushdie period of the 70s and 80s represented a time when many minorities in the UK mobilised around the secular term 'black' on the basis of our common histories of colonialism and racism. Inspired by the American civil rights movement and other progressive global movements for independence and social justice, we sought to challenge prejudice, bigotry and discrimination, and to forge a form of anti-racist politics that was capable of bridging the gap between anti-racism, feminism and socialism. We sought to build solidarity based on challenging all kinds of oppression anywhere, everywhere and all at once.

The post-Rushdie period followed the Ayatollah's fatwa against Rushdie amidst the rise and consolidation of regressive and even violent forms of identity politics, especially but not solely in minority communities. It is a communal politics marked by a rejection of the secular and universal principles of human rights and democratic freedoms, including the right to autonomy and freedom of conscience and expression. Disturbingly, it is embraced not only by the Right, but also by many on the Left: those who have often allied with the most reactionary forces in the belief that fighting racism and imperialism is the only game in town.

Women Against Fundamentalism (WAF) was formed in the wake of the fatwa against Rushdie. By publicly defending Rushdie we sought to disrupt a developing public consensus that this was merely a battle between freedom of speech and freedom of religion. We organised a counter protest – attended by black and white feminist women in Parliament Square – against thousands of enraged and mostly young male Muslim demonstrators calling for Rushdie's death.

In fear of our own lives, we held up placards and chanted slogans and songs that conveyed our political perspective, because this was a battle between theocrats and democrats in which we as feminists had a key stake. Feminism, we said, is in the business of dissenting from the patriarchal order which, in the name of religion and culture, justifies violence against women and restricts our right to our own bodies and minds. We argued that fundamentalist forces in every religion, if uncontested, will go on the offensive, and women will be amongst the first casualties of their bid for absolute power.

Ironically, that moment also encapsulated our simultaneous struggle against racism when we found ourselves challenging a white racist and fascist mob who, having arrived at the scene, saw as us the easier targets upon which to focus their own politics of hatred and exclusion.

Three decades later, we are living with the legacy of failure: the failure of democratic states and the Left alike to challenge religious fundamentalism and to safeguard the principles of democracy and citizenship. The lurch towards political and religious authoritarianism has brought with it the normalisation, and even celebration, of a culture of intolerance and censorship - one aimed at silencing any dissent, from women as well as religious and sexual minorities, writers, journalists, artists and all who refuse to submit.

In the wake of the assault on Rushdie, we understand now, as we understood in 1989, that Rushdie's battle is every woman's battle. It is the battle of all of us who stand on the right side of history. The Ayatollah will not have the last word.

Read the Feminist Dissent statement here, echoing the 1989 WAF statement.

Pragna Patel will talk more on the issue of feminism and secularism, including Southall Black Sisters' support of Salman Rushdie, at the 2022 Bradlaugh Lecture at Manchester Art Gallery on October 1st. Find out more and book your place.

The silencing of Salman Rushdie must not succeed

Posted: Sat, 13th Aug 2022

The best way to show solidarity with Salman Rushdie is by making sure his voice continues to be heard, says Stephen Evans.

The attack on Salman Rushdie on Friday was another in a long line of attacks on the very bedrock of liberal democracy: free expression.

It was a shocking attack. One of Britain's most successful authors, violently and repeatedly stabbed as he was taking the stage at a bastion of free speech – the Chautauqua Institution, which describes itself as "a community of artists, educators, thinkers, faith leaders and friends dedicated to exploring the best in humanity".

Ever since the publication of The Satanic Verses in September 1988, Salman Rushdie has come to symbolise the battle between two conflicting ideas: freedom of expression and a medieval concept of blasphemy.

Rushdie's novel, inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, instantly enraged reactionary Muslims who found the book offensive and accused Rushdie of blasphemy. India banned the book just nine days after it was published in the UK. Pakistan and Saudi Arabia swiftly followed suit. In 1989 the Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran issued a 'fatwa' calling on "all valiant Muslims" to kill Rushdie "without delay, so that no one will dare insult the sacred beliefs of Muslims henceforth." The British government placed Rushdie under police protection, and he was forced into hiding.

The events marked a low point for community relations in Britain. British Muslims were poorly served by their self-appointed community leaders. Iqbal Sacranie, a former Secretary General of the Muslim Council of Britain, remarked: "Death, perhaps, is a bit too easy for him, his mind must be tormented for the rest of his life unless he asks for forgiveness to Almighty Allah."

Rushdie resurfaced in the late 1990s after almost ten years of isolation and cautiously resumed more public appearances. Since then, he has lived openly and courageously, refusing to submit. "How to defeat terrorism? Don't be terrorised. Don't let fear rule your life. Even if you are scared," he reasoned.

But the 'Rushdie affair' gave rise to an insidious new stealth blasphemy code, with transgressions punished not by law, but by death, or at least the threat of it. As Rushdie himself identified: "'Respect for religion' has become a code phrase meaning 'fear of religion'. Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect."

But a string of Islamist atrocities has scared many into submission. Images of Muhammad are routinely censored. Criticism of Islamic practices is branded 'Islamophobic', and anything deemed offensive by fundamentalists is quickly shut down. A climate of self-censorship has emerged.

But Rushdie recognises that we cannot, as individuals or a society, be cowed by violent extremism or afford to place religion off limits for critical examination, literature, art or satire.

Pandering to fundamentalism is not a road to an open, tolerant or peaceful society. The Islamist demands will never be satiated. As the late Christopher Hitchens, a close friend of Rushdie, said: "We cannot possibly adjust enough to please the fanatics, and it is degrading to make the attempt."

We can't match their fanaticism, but we must match their resolve. Citizens of all faiths and beliefs need to stand side by side and demonstrate that we hold as firmly to our core values and freedoms as they hold to their warped extremist ideologies.

And political leaders must show leadership. That means no more half-hearted commitments to free speech. No more panicked pandering to offence takers. And no more victim blaming. Let's never lose sight of the fact that the responsibility for violence lies with those who perpetrate it.

Salman Rushdie once said that the writer's great weapon is the truth and integrity of their voice. The best way to show solidarity with him is by never allowing that voice to be silenced.