Encouraging evangelism in public services will promote division, not divinity

Posted: Tue, 31st May 2022 by Megan Manson

A survey reveals members of the public generally get along well with Christians – but feel less enthusiastic about proselytism. Megan Manson says this should be a warning to politicians who want faith groups to be free to preach when delivering public services.

There have been increasingly aggressive moves to put faith groups in charge of delivering public services.

In 2020, Conservative MP and evangelical Christian Danny Kruger published a report calling for the government to "invite the country's faith leaders to make a grand offer of help" in public services, as part of the government's 'levelling up' initiatives. This, he said, should be in exchange for a "reciprocal commitment from the state".

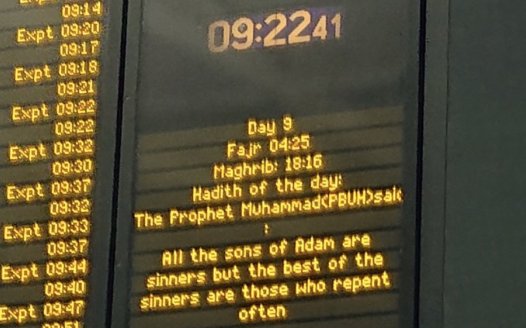

The idea of faith groups running community services makes many people uneasy. There are reasonable concerns that some faith groups can and do use these opportunities to proselytise to vulnerable members of the public, and that some groups may discriminate against service users, employees or volunteers on the basis of sex, sexuality, religion or belief. But Kruger's report dismissed such concerns as "faith illiteracy" and "faith phobia".

Hot on the heels of Kruger's report, the all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on faith and society quietly removed the non-proselytising clause from its 'faith covenant'. The faith covenant is an agreement between faith groups and local authorities which lays out a set of principles that guide interactions between them and the general public.

In the past, the NSS has publicly supported the faith covenant, particularly because the covenant specified that faith groups have to deliver their services "without proselytising". But minutes from the APPG's October meeting reveal some faith groups objected to this clause, hence its subsequent removal. This now weights the covenant very much in the favour of faith-based agendas rather than public wellbeing.

Then in September, the government announced a new £1 million ' faith new deal' pilot fund exclusively for faith groups that provide community services. Giving public money to groups on the basis that they are religious seems to fly in the face of equality law, but despite repeated requests from the NSS, the government has yet to justify discriminating against non-religious community groups in the provision of this fund.

Kruger, the APPG and all other parliamentarians so keen to roll out the red carpet to faith-based community services would do well to read a new survey from a coalition of Christian groups including the Church of England, the Evangelical Alliance and HOPE Together. The report reveals that whatever Christians feel, the non-Christian majority is in no mood for evangelism – and that proselytising can drive a wedge between Christians and their non-Christian neighbours.

The 'Talking Jesus' report, released in April, found only 6% of the 4,000 UK adults surveyed are "practising Christians", i.e. Christians who go to church at least monthly, and pray and read the Bible at least weekly. Meanwhile, 52% are not Christians – results that are consistent with other recent surveys.

But the 6% who are practising Christians feel very strongly about the need to spread their faith. Seventy-five per cent agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, "It is every Christian's responsibility to talk to non-Christians about Jesus Christ". Fifty-nine per cent said they are "always looking" for opportunities to talk to non-Christians about Jesus.

The results demonstrate that concerns about Christian groups evangelising while delivering public services are far from being the result of 'faith illiteracy' – Christians themselves are saying they consider it a duty to use every opportunity they can to share their faith with non-Christians.

And how do the non-Christians react to this? The survey results are eye-opening.

Over half (55%) of non-Christians who had conversed with practising Christians about Christianity disagreed with the statement, "I felt more positive towards Jesus Christ". Even more, 60%, disagreed with the statement "I wanted to know more about Jesus", and 73% disagreed with "I felt I was missing out by not sharing their faith". Nearly a quarter (23%) indicated that the conversation made them feel uncomfortable. Christians evangelising to non-Christians are in fact having the opposite effect of that intended – they are actively turning people off Christianity.

What's rather sad is that over half of non-Christians (51%) disagreed with the statement "I felt closer to the person in question" after having a conversation about faith with a Christian. Attempts to evangelise, however well-intended, seem to be leaving most non-Christians feeling alienated from their Christian acquaintances. A profound demonstration of how divisive unwanted proselytism can be.

This is particularly dispiriting in light of the real potential of meaningful friendship between Christians and non-Christians. Non-Christians are highly complementary of the Christians they know – the top qualities they ascribed to them were "friendly" (62%), "caring" (50%) and "good humoured" (33%).

What they don't like is the Christian church. The top two traits non-Christians ascribe to the church are "hypocritical" and "narrow minded".

The fact that non-Christians evidently have warm feelings towards the Christians they know, but feel much colder towards proselytising and to the church itself, speaks volumes about the British public. Far from being 'faith phobic', they are tolerant, even affable, towards Christians. They just don't want Christianity thrust upon them – a religion they consider hypocritical and narrow minded, which considering its treatment of LGBT+ people and women, is not an unfair assessment.

Unfortunately, the authors of 'Talking Jesus' seem oblivious of the implications of their own findings. In their conclusions, they stress the importance of continuing to evangelise – including in the public sector. The report says: "The call to churches is to work with the schools where they live to encourage and enable faith to flourish and develop as children grow in these environments". School evangelism is especially contentious – children are particularly vulnerable and unable to escape unwanted proselytising easily in the school environment.

'Talking Jesus' reveals a clash between the increasing non-Christian majority who are happy to get along with Christians provided they aren't preached at, and a shrinking Christian minority who see it as their duty to spread their faith. Regrettably, it is the latter that the government's pro-faith 'levelling up' schemes will privilege and empower. If this survey is anything to go by, letting religious groups use public service provision as a mission field will end in tears – both for the public who don't want to hear about Jesus while asking for help, and for the well-meaning Christians who will no doubt feel rejected and hurt when their 'good news' isn't well received.

What is more likely to foster good relations between faith groups and their community is to ensure offers of help are given without any religious strings attached – no proselytism, no discrimination. A secular approach to public services, regardless of the ethos of the community delivering it, is what the government should be encouraging.

Protect secular public services

Outsourcing to religious organisation threatens to undermine equal access and religious neutrality. Join our campaign to protect secular public services.