We’ll all suffer if we let religion dictate how public servants do their jobs

Posted: Tue, 1st May 2018 by Chris Sloggett

Politicians have hung a coroner who stood up to religious groups out to dry, says Chris Sloggett. And they've revealed how foolish we are to indulge individualistic demands for state services to accommodate religion.

When Mary Hassell isn't appearing in court, she's often doing something necessary but unpleasant. Hassell is the senior coroner for inner north London. When someone dies in a car crash or a woman is killed by her partner, she and her team have to find out the grim details.

Here are a few examples of the work she's done in recent months. She heard the case of a mute, autistic boy who starved to death while clinging to his mother's dead body – and recommended action to prevent something similar from happening again. She held a leisure centre, a care provider and a dental clinic to account over failures which contributed to deaths. Less than a fortnight ago she put a council on notice over the fact none of its staff were responsible for checking fire detectors in the properties it owned.

And as London's spate of violent deaths continues, we can safely presume she and her staff have spent plenty of time dealing with its victims. They've turned up and got on with it. But they've done vital work which will help to protect us all.

Unfortunately Hassell's name has come to public attention for another reason. In October she made a decision all professionals make at some point. She decided to prioritise her workload to make it manageable. In doing so she invited opprobrium from many people who had probably never even bothered considering what her day-to-day priorities might include.

Her office was tasked with carrying out a post-mortem on a dead Jewish man. In the following hours Stamford Hill's Adath Yisroel Synagogue and Burial Society (AYBS) repeatedly called and emailed to insist that staff do the work the following day. The office was short-staffed; it finished its work on the body four days after the death.

Hassell then did what she had to: she stood up for herself and her officers, and said no deaths would be "prioritised in any way over any other because of the religion of the deceased or family".

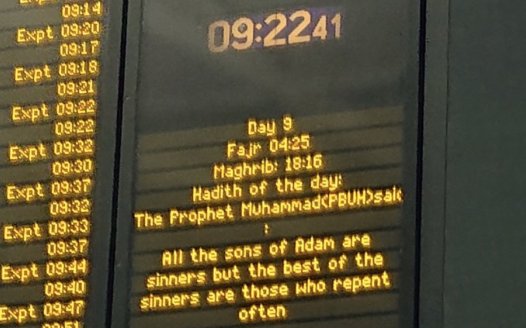

Faith leaders responded angrily, arguing that Jews and Muslims would not be able to observe the tradition of burying their dead immediately. Relatives of the dead continued to make impossible demands. In December one woman called her office 210 times; Hassell's staff managed to return her father's body on Christmas Eve, four days after his death.

Much of the commentary was highly personal. And the Board of Deputies of British Jews not only wrote to the lord chancellor and the lord chief justice to ask for Hassell's removal. In an astonishing fit of entitlement it released figures showing how much it cost the taxpayer to defend her against a previous judicial review – which it had brought.

More depressing was the craven response of politicians. The prime minister said the Ministry of Justice was speaking to the chief coroner "to see what more can be done". Jeremy Corbyn and Emily Thornberry complained to the chief coroner. The MPs David Lammy and Matthew Offord and the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, put the boot in. The London Assembly passed a unanimous motion condemning Hassell and resolving to write to the chief coroner and other judicial office holders.

Then came the judicial review, brought by AYBS, into Hassell's new policy. The chief coroner, who had initially described it as "excellent", told the court it was "over-rigid", "not capable of rational justification" and "not lawful".

On Friday the court ruled against Hassell's policy. In the aftermath the Board of Deputies again called for her to go and claimed a "basic function" of a coroner's role was to "uphold the religious freedom of diverse communities". The politicians again hung her out to dry. Corbyn, supposedly the great champion of the public servant, was particularly vociferous – he called her decision-making "completely unacceptable" and accused her of putting "barriers in the way of families trying to lay their loved ones to rest". The press coverage overwhelmingly featured reaction from religious groups rather than the pushback against them.

Hassell's defeat is disappointing, but at least the judgment includes the qualification that the coroner has a "margin of judgement". Public servants should be aware: this decision doesn't mean they legally have to do what the religious tell them.

But they will need support. That means powerful people must stand up to religious groups' demands to be treated as consumers by the state. And as this episode has revealed, those who wield power in British society are instead foolishly indulgent of them.

Cases such as the Hassell one inevitably bring nuance (her 'cab-rank' policy – first in, first out – appears to have faltered because, in the cold light of a courtroom, it looked like this was lacking). Dealing with bereaved relatives is inevitably sensitive, and the religious groups have one semi-fair point: a degree of flexibility can sometimes suit everyone. Some families may not mind a longer wait to get bodies back. Guardian columnist Peter Ormerod's words – "I'll happily give up my place in the queue for someone who cares more deeply about it than I do" – appear on face value to be compassionate and reasonable.

But note the use of the first person singular. Religious pressure groups like this. When they deploy individualistic language they can demand special treatment while telling others to butt out. They cite 'parental choice' to defend taxpayer-funded faith schools, including those which promote intolerance. They claim exemptions to laws, then ask critics who we are to judge.

This allows the loudest voices to get what they want; sharp-elbowed parents, for example, get the education they want for their children. Meanwhile the unassertive lose out. If the state has to do what the religious want, the non-religious will be pressurised to play along.

And even less attention will be paid to the people we all rely on: public servants who do difficult, sometimes unpleasant, often stressful jobs. Coroners have many other priorities – and responsibilities to thousands of people. They need tools to resist those who ask for the impossible. If we expect them to provide a bespoke service to everyone (without an unrealistic increase in public expenditure) they will do their jobs badly or give up and be replaced by worse people.

That should worry all of us. We all have an interest in protecting public services which work, are affordable and treat us fairly. And we can only do that while giving the religious groups what they want if we answer two awkward questions.

If we put the religious first, how can we make sure others will not be disadvantaged? And how can we make sure we do not place an unreasonable burden on the state, driving out staff, undermining solidarity and damaging the common interest?

Amid all their bluster during the Hassell affair, neither the religious groups nor the politicians have given us an adequate answer to either of them.

While you're here

Our news and opinion content is an important part of our campaigns work. Many articles involve a lot of research by our campaigns team. If you value this output, please consider supporting us today.