Faith in public services?

Posted: Thu, 2nd Jun 2016 by Alastair Lichten

An increased role for religious organisations in the provision of public services would be disastrous for both the public and faith sectors, argues Alastair Lichten.

The Oasis Foundation recently launched a report arguing that the aspirations of the 'Big Society' have not been met. The report correctly points out that the third sector lacks the capacity to take over core public services and that local authorities have concerns over outsourcing services to certain groups, including faith-based groups.

Christian commentators are often keen to document the contribution of religious organisations to the third sector and social activism, but they always fail to demonstrate why it should be the state's role to build this capacity or why local authorities shouldn't have legitimate concerns about religious groups running services.

A few weeks ago prominent Christian MPs in the House of Commons spent almost two hours in an "incredibly important" debate, agreeing that faith groups do a lot of good in communities, and that any reticence by local authorities to have more religious groups running services is just 'fear', 'aggressive secularism' and 'religious illiteracy'.

Every time that religious privilege is in some way undermined (or even if the Government is not sufficiently gushing in its praise of the 'faith sector') we hear apocalyptic predictions from religious leaders that all the volunteering and social action done by faith groups is going to somehow disappear. I imagine this sort of privileged moaning is particularly insulting to many people of faith.

The strawman of 'aggressive secularism' and moral panic over 'religious illiteracy' do little to aid clear thinking or address the concerns of people of all faiths and none have about the future of public and third sector service provision.

Best practice for third sector organisations interacting with and supporting the public is usually marked by four characteristics:

Those advocating for faith organisations taking over more public services risk undermining these restrictions, which exist to protect both the public and third sectors.

Some would have you believe that they are simple asking for the poor, put upon faith sector to be treated like the rest of the third sector, for there to be a free market with a diverse range of groups. But too often what is being advocated is a biased market, where faith groups are privileged and the secular and public nature of public services are undermined.

1. The organisation provides a supplementary rather than core service.

Of course our secular public services have always been supplemented by voluntary and third sector groups many of whom have a faith basis. Macmillan nurses funded by donations are a lifeline to many cancer patients. But it wouldn't be possible or desirable for Macmillan to take over the NHS. Residents of a rural village may welcome a Church group opening a community library but be understandably concerned about their public library being closed and moved to a church hall.

According to Oasis's own polling 55% of people had little or no confidence in Church groups running "Crucial social provisions such as education" only 6% had a lot of confidence. 65% had no confidence in Church groups running "Crucial social provisions such as healthcare" with only 2% of people expressing a lot of confidence. Move on to more supplementary services and confidence in Church groups grows with 64% having a lot or a little confidence and only 7% no confidence at all.

2. The organisation is run in and provides a service in a non-discriminatory manner.

In Southampton £1m has been cut from the children's services budget and £60,000 handed over to a Christian organisation to 'help struggling families'. Safe Families for Children's online donation form doesn't ask what Church you're from. But their volunteer forms all do.

Want to support this innovative co-operation between the public and faith sector, why not apply to be a Programme Director or a Regional Operations Director? You may be delivering a public service and receiving public money, but I'm afraid you will need to be a Christian. Naturally, this discriminatory requirement would be unlawful in a local authority or secular charity.

Safe Families for Children's may provide a valuable service and if they weren't publicly funded or they followed the four principles I'd have no secular objection. In a free society a private group should be free to organise for the benefit of its own members and to ensure its doctrinal purity. But when public money is involved surely we're right to expect the services they fund to be non-discriminatory?

Many religious groups do provide services without discrimination. Not all religious groups go out of their way to create a 'Genuine Occupational Requirement' to restrict jobs based on religion. But some do and this is a legitimate concern. If religious providers are to be treated like any other provider then we stop the a priori assumption that religious = good and that religious discrimination is justified or 'not really a problem'. And we should end the religious privilege of overly broad Equality Act exemptions.

These exemptions are not fit for the modern third sector and reflect an outdated view of an amateurish sector made up of mainly volunteers. Theos, Oasis and other 'big society' advocates seem to want a modern, well-resourced third sector. But with the faith section of the sector enjoying all of the benefits of professionalization and few of the restrictions.

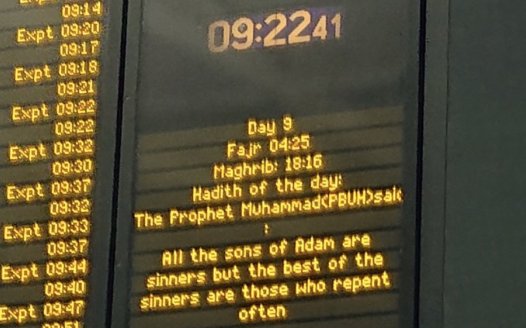

3. The organisation does not use the opportunity of providing the service to advance a partisan or ideological agenda.

On the one hand the religious service advocates argue that proselytization isn't really a problem and service commissioners don't need to be at all suspicious. On the other hand they argue that religious groups should be given more room to use public services to proselytize – and that service commissioners still shouldn't be suspicious.

Luckily (outside of education) direct proselytization by religious groups running public services is rare – usually a case of an overzealous individual rather than an organisational ethos. When an ideologically driven group runs a public service, appropriate and proportionate steps should be taken to ensure that agenda doesn't affect the service.

If the contracts of religious providers of publicly-funded services included unambiguous equality, non-discrimination and non- proselytising clauses in them, perhaps the public would have more confidence in religious organisations delivering services. It would also ensure religious volunteers could be clear about appropriate boundaries.

4. The relationship between the public service and the third sector organisation is open to scrutiny.

During that recent debate on the 'faith sector', Fiona Bruce and others called for local authorities to have religious advisors and give special attention to the faith sector. A call since taken up by the Church Times. Apparently, religious groups' capacity is so good that they should run more public services, and their capacity is so poor that the state should give them special support to build it.

We're also told that religious groups should be treated 'just like any other group wishing to provide services' but at the same time they should have 'special advocates' and never have their "motives" questioned.

Devon and Cornwall Police recently advertised for a faith co-ordinator. Not a third sector outreach co-ordinator to work with community groups of all types. No. A religious enthusiast to help build up faith groups and help them win funding bids – all at public expense. One such organisation specially highlighted in the role has been accused of incorrectly applying a Genuine Occupational Requirement to restrict a full time role to a Christian. HMRC are looking into the same job advert over possible breaches of minimum wage legislation.

Given historical problems of discrimination in the police, recruiting a faith co-ordinator can seem like an easy, tokenistic gesture. But minority faith communities continue to be let down by such an approach that assumes self-appointed 'community leaders' have the capacity or legitimacy to represent an entire community.

If you want to see secularism in action think about your last trip to an NHS hospital. While sharing the frustrations of a waiting room you probably sat next to fellow citizens of all backgrounds, faiths and beliefs. Our secular NHS treats them simply as patients, irrespective of their beliefs. Perhaps your doctor was motivated to become a doctor by their faith or belief, but our secular NHS means that their personal beliefs didn't help or hinder them to get where they are and that their faith in no way interferes with the way you're treated. And this is precisely the way it should be when public services are being delivered.