Publicly funded services shouldn't be a platform to proselytise

Posted: Fri, 6th Nov 2015 by Stephen Evans

Any attempt to give faith-based organisations more room to discuss religion when running public services risks making their services less inclusive. Besides, public money shouldn't be funding evangelism, argues Stephen Evans.

A new report from the Christian think-tank Theos argues that those commissioning public services shouldn't be suspicious of faith groups, or allow concerns over proselytism to be a barrier to closer relationships with faith-based organisations.

In The Problem of Proselytism, the problem is the contested definition of the word proselytism rather than proselytism itself – which, they argue, isn't really a problem at all.

Secularists will want to carefully scrutinise any and all relationships between religion and government and this particularly extends to those acting as agents of the state, using public money to deliver public services. It is essential that publicly funded services remain inclusive and accessible to all – regardless of religious background, gender, sexual orientation. When such services are delivered by faith-based organisations, an obvious tension becomes apparent, particularly given our religiously diverse yet secularised country. Most such services are likely to be offered by Christian organisations, and while Christians are the largest religious group, practising Christians are very much in the minority.

There is a perception of a secular insistence that faith groups should play absolutely no role in public life or in welfare or the provision of public services. That's just a straw-man used to undermine secularism. There is a considerable amount of unease about public services being run by religious organisations, but few secularists are as dogmatic as to insist that no welfare or public services should be run by faith-based organisations.

Most will recognise that social action by faith-based organisations has contributed enormously to the welfare of our society. There are somewhere in the region of 54,000 places of worship in the UK and many of them will be carrying out some sort of welfare work – often small-scale, but very valuable to the communities they serve.

There is however an understandable concern that as the Government encourages faith groups to 'fill in the gaps' in public service provision, the risk of discrimination against employees and service users increases, as does the risk of faith groups using public money to proselytise. Faith-based organisations should be free to compete for contracts, but only on the same basis as their secular counterparts.

With the exception of education – where proselytisation and faith-based discrimination is rife – the majority of faith-based provision in the UK is non-proselytising and, outwardly facing at least, secular in appearance. Any overtly religious provision would be unwelcoming and off-putting to many service users – and staff and faith based organisations (FBOs) are well aware of that.

But Theos is keen for us not to talk about 'proselytisation' because it thinks the word itself is loaded. In refusing the term, it claims "churches and FBOs are not attempting to obfuscate, using different words to talk about what everyone else calls proselytism, thereby dodging secular bullets" – but the whole report strikes me as an attempt to do just that.

Theos is clearly attempting to carve out wiggle room to enable faith-based organisations delivering public services to be able to be more open about their faith ethos and use the opportunity to evangelise and 'share the Good News of Jesus Christ'.

Theos agree that there is "no justification for making the provision of aid or assistance conditional on expressing religious beliefs", but would like to see those delivering public services to be able to "express their beliefs openly".

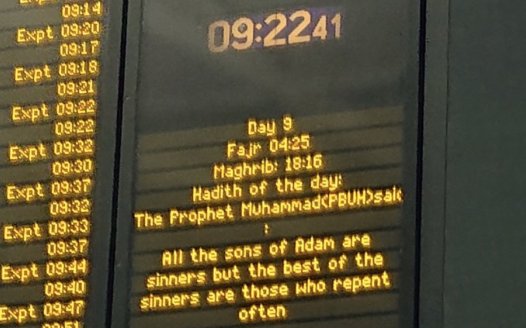

We can wax lyrical over definitions of proselytisation but we know it when we see it or experience it. At best it's irritating and uncomfortable, and at worst it constitutes harassment. People accessing public funded services, many of them vulnerable, rightly expect to receive such services without the unwanted intrusion of other people's religion.

Public services must be underpinned by principles of equality and a respect for the rights and dignity of the individual service user, not the rights of providers to express their religious opinions.

Most public services are currently in the hands of secular bodies, and there is no evidence that the public is dissatisfied with this. On the other hand, the main example of non-secular public service provision is state-funded religious schools, to which there is a significant amount of opposition.

What the vast majority of the British public surely want is inclusive, accessible public services without any obvious identification with particular religions or beliefs. Allowing public service providers the freedom to raise religion in interactions with those receiving services runs the risk of undermining social cohesion and is a recipe for wholly unnecessary conflict and tension.

Some years ago a Bishop argued in the House of Lords that the Church should not face regulation when welfare and health care are handed over to it by central and local government. The Bishop of Carlisle said that when the Government commissioned the Church to provide welfare services, it should do so on trust and not subject it to regulation. This is the sort of 'light touch' approach Theos would seem to welcome.

But when President Bush introduced the 'faith based community initiative' in the United States, which saw huge amount of federal funds channelled into Christian churches' welfare programmes – such groups were ostensibly forbidden from using the money for proselytising or discriminating against recipients on the basis of religion. However, a lack of adequate safeguards and monitoring, and hardly any regulation meant that there was nothing to prohibit religious discrimination against prospective service users.

That's not a route we want to go down.

Proselytisation in welfare provision may not be a massive issue now, but as the role of faith based organisations expands, it could well prove to be a flashpoint in the future unless clear rules of engagement are established.

FaithAction, a network of faith-based and community organisations, which provides the secretariat for the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Faith and Society, promotes a Covenant – a set of principles that guide engagement between Local authorities and faith groups that commits FBO's to "serving equally all local residents seeking to access the public services they offer, without proselytising, irrespective of their religion, gender, marital status, race, ethnic origin, age, sexual orientation, mental capability, long term condition or disability".

Theos describe this approach as "flawed" and say should such principles shouldn't adopt a 'thou shalt not' but a 'thou shalt' approach – arguing that FBOs are not deserving of particular suspicion.

But whilst many FBOs will be happy to provide services in a secular fashion, others will always want to 'push the boundaries'. Let's not forget religious organisations demanded (and won) special exemptions from equality legislation to enable them to discriminate against their employees narrowly on grounds of gender and sexual orientation (for leadership roles) and more widely on the basis of religious belief. We're all aware of individual Christians and the lobby groups behind them campaigning for exemptions to allow their 'religious conscience' to permit them to refuse services to gay people. Catholic adoption agencies fought tooth and nail to be allowed to exclude same-sex couples from consideration as prospective parents. The Church of England recently blocked a gay clergyman from taking up a post as a hospital chaplain because he had the temerity to marry the partner he loved. Religion can be highly judgemental, our public services should not be.

Proselytism may be wholly counter-productive, but 85% of practising Christians say they believe it is "important or very important" to talk to non-Christians about Jesus. And if faith schools offer a blueprint for faith-based public service provision we can look forward to a proselytisation on an industrial scale in the future.

In an open and free society Christian mission is a perfectly legitimate activity – but not when done using public money provided to deliver public services.

Nobody wants to regulate the ordinary conversations that take place in day to day life, but those delivering public services need to be aware that welfare provision is not an appropriate platform from which to proclaim the gospel.

Contracts with religious providers of public services should have non-discrimination and non-proselytising clauses that clearly spell out that unsolicited discussions about religion or belief with service users or attempts to convert them to a particular religion or belief are unacceptable and could constitute harassment.

If this were done, levels of suspicion and mistrust of faith-based organisations would be considerably lessened. Local authorities would feel safer to hand out scarce resources in the knowledge that they would be used to provide the service in a neutral and inclusive manner – with no attempt to promote any particular religion. Then, perhaps, there really would be no problem of proselytism.